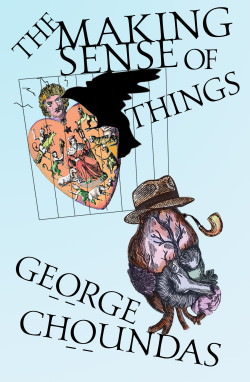

The Making Sense of Things

George Choundas

FC2, 2018

Reviewed by Katharine Coldiron

George Choundas’s debut collection is oddly shaped. The stories are either quite short (a page, five pages, perhaps nine) or quite long (twenty-eight pages, thirty-five pages, even forty-three). Miniature stories and lengthy stories call on such different skill sets that a writer who collects both between one set of covers must be an exceptional craftsman indeed. Fortunately, Choundas qualifies. His stories are enchanting, remarkably bold and confident, refreshingly resistant to precedent.

Thus, it’s suitable that this collection won the Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize from FC2, and that Choundas himself has won a variety of other awards, such as the Katherine Anne Porter Prize in Short Fiction and the New Millennium Fiction Prize. But it’s not just the collection that’s oddly shaped. The individual stories also proceed in intriguingly unfamiliar patterns. For example, “Kennedy Travel,” which hops close third-person perspectives from a husband to a wife, proceeds in a curious pattern: a solid, sensible beginning, an utter left turn, a time-lapsed middle, an utter right turn, and an ending that is not falling action so much as it is solid ground, again. Through all of this, Choundas manages a profound recognition of the particular:

[T]he family record—every family has one, accreting bit by bit with information so curt and desultory and incidental, heard through a sweater being pulled over a head, dispensed as the good dressing is retrieved from the fridge, that there should be no room for mendacity, no time for invention, and the cumulative result seems solid and unimpeachable as a reef…

The use of la mot juste is a notable feature of all of these stories. In the longest, “Abridged,” which toys with the writer’s struggle to write (yes, roll your eyes, but the result is much better than you’d imagine), “[a] dog barked somewhere. At the same moment a waft of rot passed through. The heavy afternoon connected them. The dog had found something dead. Or death had jammed like a chicken bone in the dog’s throat and dislodged barkward.” In “Pleasantville,” the narrator says that “before age twelve, I was a coil of spastic and oblivious cartilage.” That story, which is as close to a masterpiece as a short story can come, is full of organic surprises, two of which are entwined with dizzying grace.

The impulse is to compare Choundas to George Saunders, because some of the stories in The Making Sense of Things lean on semi-supernatural foundations (sentient woodpeckers, a “Little Red Riding Hood” retell). But that won’t do. Saunders and Choundas are startling in similar ways, but Saunders is sprightly where Choundas is measured, and Choundas’s intentions as a storyteller are not so easily distilled to “dancing past the graveyard” as Saunders’s are. There’s something in Choundas’s stories about life and how to live it that challenges the reader to look up and around, instead of back down into the book. “On the Far Side of the Sea” turns its readers’ expectations of love’s triumph around and then around again; the result makes us wonder about our own un/happy endings, rather than merely what the characters are undergoing.

The unusual shape, the sincerity curling at the edges toward sentimentality, the impeccable verbiage—there must be a name for this kind of writing. A clue may be found in Seth Abramson paraphrasing David Foster Wallace:

The…form of metamodern writing would also be unrecognizable as either “conventional” or “experimental.” Instead, it would look nothing like it was supposed to — a metamodern poem wouldn’t look like either a conventional poem or a postmodern experimental poem…

Choundas’s stories don’t feel postmodern: too much feeling, too focused on narrative. But they don’t feel at all conventional: too fresh, too many K-turns on strange streets. Perhaps these eccentricities can be explained with Abramson’s classification of metamodernism. Or perhaps Choundas is simply that rare writer—a true original.