21 DAYS

Janice Margolis

DAY 1:

The Ebola ambulance men take Mama’s fevered body. They dig out the dirt from underneath her and take that too. Splash. Spray. Everything gone. Can’t touch Mama’s hand. Can’t take Papa’s color rope from her wrist. Me naked in the corner. Dwe up in our palm tree gets a good look. His eyes don’t lie. He likes all of me.

A white grub with black tusks sprays me. It stinks. It stings. My skin cracks so wide a lion enters. Its fur insulates my lungs. More grubs come. Blanket Grub. Bowl Grub. Spoon Grub. Water Grub.

Bucket Grub nails a bar across the window so I can’t crawl out then ties a blue bucket to the bar. No Dirt Grub comes to fill the hole where Mama fevered. The hole is wider than my arms and big as Papa. It will be a hungry deep ghost. If I fill it with water, it will never be thirsty.

Clothes Grub brings a green-and-gold dress and points a white gun at my forehead. My heart crawls away. It will come back as a coconut, my husk hair woven into President Sirleaf’s doormat, my heart beating from the soles of her shoes. Clothes Grub shows me a red-flashing number. 98.4. If only I could get that grade on my algebra test. The grub dances but he’s not from Liberia. His feet are dead. He may be from America. Where the slave ships took so many. Where the slave schooner Feloz tried to take my mama’s mama’s mama in 1829.

My eyes want to hide inside the white gun and flash memories onto others’ foreheads so they’ll know what it means to be someone else.

I am not where I am. I am not this girl. I am concealed. Aboard the slave ship Feloz. I am seasick.

I put on the green-and-gold dress. It stitches my breasts together. It’s soft as Mama’s favorite hen, I tell clothes grub. Words can’t make it through the grub’s tiny tusk holes. Papa gave it to her. He’s in the mines. Uncle took Obi and Esther into the jungle. You took my schoolbooks. History won’t wait. Grade 9 exams won’t wait. Rice won’t wait. The rice needs me. Obi and Esther need Mama. They’re six. They couldn’t decide whom first, so they came together. History’s going to forget Dwe and I are promised. He hasn’t given Papa the letter yet. Hasn’t brought Papa the rice bowl. The kola nut. The palm oil. The white chicken. Bodies won’t wait. What do I do?

Clothes Grub writes in the dirt: 21 days.

DAY 2:

Before yesterday there was a straight path from my heart to Mama’s. A straight path from the end of this village to the beginning of another country. There is nothing in that country to tell us we are no longer in this one. On Fridays Mama sold cassava gari over there. On Saturdays fufu here. It took her five minutes to walk from here to there. Everywhere people are drawing lines and circles. Don’t walk this way. You are outside. I am in. Our bodies are getting lost.

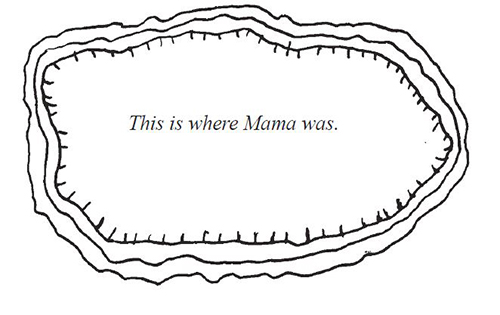

I draw a circle around the hole where Mama laid and curl up inside. Mama’s hole still has paths. Our village hatches beneath me. Uncle’s hut pokes my knee. The school separates my toes. Dwe’s roof pillows my head. When I roll over, our collarbones fuse into a new village made of teeth. The map of this village eats borders.

Miss Browne likes to open her arms wide when she teaches history. Her arms are wider than Mercator’s world. Her fingers like keys when they point at you and call your name. Miss Browne says that when we study a map, we become part of it. Our eyes enter a town but our feet stay.

On Miss Browne’s history wall there are yellowy maps with gray tapeworms cutting towns in half. Streets that die in corners. Oceans full of two-headed fish with gigantic red mouths swallowing ships. This is the same ocean that drowned our history. That still holds part of me. Miss Browne does not have a map of our village on her wall. She says none exists.

My friend Hawa stands at the window in blue rubber gloves and the wooden deangle mask we made in Grade 6. The mask’s slit eyeholes are pure night. Her breathing is scared. I tell her:

I don’t think Hawa wants to look at me, or see how big Mama’s hole is. She drops the schoolbooks, notebook, and pencils she’s collected in the blue bucket. She keeps the history book. Somebody already left one in the bucket.

Some people are so scared they’ve sent their kids to Bush School. My cousin Felicia was dragged there by her hair. Hawa will try to get a message to Papa about Mama, but soldiers are guarding the road in and out of our village. She promises to bring me rice later. Hawa has a pure heart.

Dwe drops a coconut and stone in the blue bucket on his way to the river to fish. His brothers are watching, so he doesn’t husk it for me. I press the coconut to my lips where Dwe touched it. I feel his skin on mine. The stone is sharp on one side and fits my palm perfectly. It burns to think Dwe is at the river without me. The way his arms move the oars in time with my heart.

DAY 3:

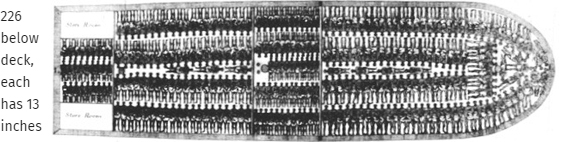

I have been told it is dangerous to dream of cheetahs, so I crawl into Mama’s hole with my history book and tell myself, don’t dream of cheetahs. On page 379 is a picture of the slave ship Feloz. I close my eyes and see the seasick girl in the ship’s hold. Waves rock my sleep. My green-and-gold dress becomes a home for endangered bush babies. They leap from hut to hut spreading our dreams.

In Dwe’s dream, his words wrap my body. “Corrugated zinc roof.” “Wild honey.” They’re like new skin that dances. A bush baby carries my word-wrapped body to the edge of the world. When I look over the side, I can see back in time to the day the Feloz set sail.

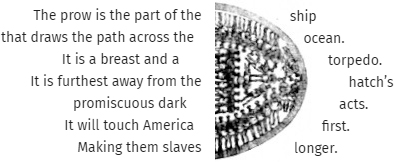

The seasick girl is shackled to two others in the ship’s prow. They sit in a row, knees bent, between the others’ legs.

DAY 4:

I draw a map of our village out of rice in Mama’s hole. I draw the path to school and from the end of the village to the other country. The guards don’t stop the rice. It could go all the way to America. The guards don’t know I’ve written my name on a grain of rice that crossed the border. I’ll join a gang of rice that will swell into an army that feeds the seasick girl aboard the Feloz.

A baby palm rat drops through a crack in the palm-leaf roof. It is the size of a small mouse. It falls into Mama’s hole, right in the middle of my village. If it’s not dead, maybe it will stay.

The rat’s tail sweeps away Miss Browne’s rice classroom and half the school. I think of Hawa and Dwe tumbling out of their desks. Of Miss Browne’s maps colonizing new territory. Africa smothering America. Europe covered in penguin poop. The baby rat scurries out of my village and across the border. If it hurries it may rewind time and catch the Feloz before it sails.

The seasick girl’s knees are younger than the knees she sits between, but older than the shoulders she sits behind. The ship’s hold is 3 feet, 3 inches in height. Its prow is 18′ X 16′.

DAY 5:

Mama,

A baby palm rat fell from the sky. It looks at me the way I looked at you. It sleeps flat on its stomach in the hole the ambulance men dug out from under you. It likes rice more than freedom. It ate the last hut remaining in the rice village I drew. I want to teach history like Miss Browne. I am teaching the baby rat about the Feloz. About your mama’s mama’s mama. I don’t know her name, so I call her the “seasick girl.”

Hawa brings me food and water. Dwe brings coconuts. Everyone’s afraid of me except the palm rat. Dwe comes to the blue bucket when he thinks I’m asleep, but I know how he sounds when he breathes. Sometimes Hawa sings near the well. If I don’t sing back, she shouts my name. Sometimes old Abraham sits across from the window and tells me what’s happening. “The old blue chicken walks in circles. There are five people at the well. Miss Browne has on an orange dress.” He doesn’t want me to forget language.

I sit inside your hole and pretend I’m aboard the Feloz, the seasick girl in front of me. My bent knees are the borders of her world. I’ve braided a map of our village in her hair.

I’ve learned how to dance with just my knees. Discovered a beat with my feet I’ve never felt before. I taught the seasick girl the beat, and how to braid a village on the head of the girl in front of her. Her feet and fingers taught that girl how to do it. Together we’ve mapped our country’s coastline so no slave ships can make landfall. We un-built the coastal forts and braided them into palm trees. Our feet have reversed the tide. Our mapped braids have erased borders.

DAY 6:

In my history book the plantation map says 1 inch = 1 foot. An arrow points at an 8-inch shack. “Slave Quarters” it says across the missing door. The master must have lashed it gone. I quarter the slave quarters with lines. My pencil point severs a fiddler slave and infant. Half the fiddler’s music and a slave baby’s foot are set free. Two other children huddle, faces so sunk they’ve lost their noses. I draw wings on their arms and an arrow pointing east toward me in their hands.

They need to learn how to play “Oh Mama.” Their hands ready to clap Liberian when the ships return. Under. Over. Back. Across. Together. Faster. Faster. Over. Under. Slap. Slap. Together. Back. Across. They watch from the shack as I teach them. Oh Mama, Mama! Oh Papa, the war! I met my boyfriend in the candy store. He bought me ice cream. He bought me cake. He brought me home with a bellyache. Mama, mama, I’m so sick. Call the doctor quick quick quick. Doctor, doctor. Will I die? Count to five and you’ll be alive.

Hawa and Dwe don’t come today. The baby palm rat whines for rice. It nibbles my finger as I tell it about the hungry seasick girl squeezed into the city below the waves. To show it how many men and women the Feloz took on at the coast, I write the numbers in Mama’s hole and add them. 336 males + 226 females = 562. I write 17 to show how many days the Feloz was out at sea, 55 for how many were thrown overboard.

My finger fills Mama’s hole with wavy waves, but when I look from the other side they are birds in flight. I join the numbers in Mama’s hole and try to forget how hungry I am.

DAY 7:

It must be Sunday. The blue bucket overflows with rice and coconuts. My stomach is grateful.

Outside is full of Dwe’s laugh. Through the barred opening, I sometimes see an elbow or foot chase past and my shoulders soften. I stand there forever, watching the dust from their game drift close. If the wind blows toward me, I breathe deep and let Dwe’s speed fill my lungs. It feels bright green. I want to battle with stones. I want to play “Who Is in the Garden” with him. We’ve been playing since we were five. In ten years he’s never caught me.

Miss Browne brings me two clean dresses and her map of medieval Europe with the red-mouthed monsters. This is to remind me how wrong people can be. When I tell her those streets were full of plague, she clicks her tongue and waves her blue rubber-gloved hands at me. She may be casting a spell or letting me know I’m a fool. It doesn’t matter. It’s so good to see her wider-than-the-world arms scatter time, I beg her to stay and tell me more about the Feloz.

Instead, she tells me how animals groom each other in the most vulnerable positions. How humans groom each other with language. Miss Browne grooms me for hours, bringing messages from classmates too afraid to come.

I stretch the map across Mama’s hole. Side-by-side the slave-quarter shack is half the size of Germany. The palm rat pokes around France, though Belgium is shaped exactly like a palm nut. There is a ghost ship on the Atlantic with twenty transparent sails and a gray hull. It’s bigger than ten countries but can only sail in circles since it’s trapped inside a square.

My foot has as many blue roads as Spain has gray ones. The vein from my big toe to my ankle is as straight as the trade winds. A grain of rice that sets sail from my anklebone easily lands in the Caribbean. I launch ten more rice ships before my foot cramps and my rescue flotilla stalls in the windless horse latitudes of the Sargasso Sea.

Beneath the map are the wavy waves, the birds in flight, and the Feloz‘s 562. I sit among them shivering. This floating coffin feels off course, my body hot and cold at once. The palm rat nuzzles my neck, chews my hair. I can see the hole it slipped through in the thatch above. It’s easy to get lost among the braided fronds. A map of trees that could be anywhere, or somewhere that hasn’t been mapped. It could be streets of circles. Circles chained. It could be somewhere that isn’t somewhere. Somewhere that isn’t a pitched roof. Anywhere that has a central beam. It could be the bottom of a boat. The keel of a capsized slave ship tangled in the Sargasso Sea. This could be what the red-mouthed monsters see. Beam and pitch and slope. Bodies braided in weed. Shackles done noising. Done rubbing. Undersea wind blowing. They could be balloons. They could be sirens luring slavers.

Where is the Feloz on the earth’s belly? I should turn its deck on history.

DAY 8:

On her way to school, Miss Browne leaves me scissors, a box of postcards she’s collected from everywhere, and a red yarn baby with seed eyes. The palm rat grabs its hand and runs off. Poor Yarn Baby. Some of the postcards say strange things that no one would ever say to Miss Browne. Some are addressed to people with funny names. There are more trains and statues than can possibly exist. One postcard has a picture of a man on stilts and is addressed to London. It says: This is a race, Myron. That’s all it is. A race. I don’t know how else to put it. A race. I wish it wasn’t, but

Another has a glass pyramid floating on water. Above it is a three-quarter moon. Either the glowing pyramid lights the moon, or the moon makes the pyramid glow. The pyramid’s face is hundreds of diamonds braided together from triangles. There is no way to know if 1 inch = 1 foot, or 1 inch = all of medieval Europe. It could be a map of an Egyptian glassmaker’s shop, except on the flip side it says: Le Musée du Louvre. There is a smudged fingerprint on back. The postcard may or may not have made it to Mary in Tulsa, OK 74112. I hope not. If I were Mary and received this beautiful pyramid lighting the moon, I would want nothing written at all. I would not want: I think you know I love you. Do you?

I cut out the man on stilts and the glowing pyramid, and stand them in Mama’s hole. The man on stilts is taller than the pyramid, but not tall enough to walk over it, so I cut out a railroad track, lean it against the pyramid for him to climb, and set a train on the pyramid’s roof so he can get across town. There are so many fountains to lay side-by-side they spout an ocean. I free the trapped ship sailing in circles inside the square. Free the nose-less slave children, the fiddler slave with half his music, the infant slave with half a foot. They board the ship and sail for the pyramid. If only I could cut out myself and walk on stilts. See Dwe the way a coconut does.

The yarn baby is no more. Red wool twists through the hut, intersecting at tangled figure eights. The palm rat sleeps in a knotted cul-de-sac having worn itself out. While it rests, I will map it a village different from the one we live in.

DAY 9:

The map of this hut is 1 foot = 1 foot. My thumb knuckle = 1 slave-quarter inch. The baby palm rat = 3 thumb knuckles without its tail. When I close my left eye, the tip of my thumb can swallow the full moon. When I close my right eye and open my left, my thumb can erase Dwe and the palm tree. No matter which eye I close, Mama’s hole swallows my whole arm.

There are dimensions inside my body. Someone is lighting a fire. Throwing red-hot sun into my stomach. It’s possible I ate the glowing glass pyramid and I’m full of chattering diamonds whispering nonsense. Love is a broken line of ideas. It used to be the inside of a person never caught fire. I might be covered in bush babies. I might be a hut in the other country. There is seashore between my eyes, seashore and ghosts sitting on coconuts hatching sounds. A diamond taps against my teeth, so eh…I might have to, eh…ride a cheetah to Monrovia. The baby palm rat is lost in the village I built. I never gave it a name. It’s Baby Palm Rat, or Palm Rat, or It. I think I’m crying. Or falling toward something red and wet. I hear Eh, about that, so, I think it’s time to look down and see whether you’re falling. I may look down. May see Baby Palm Rat riding a cheetah. May see the glowing glass pyramid enter me. I’m dizzy with diamonds and full of miniatures. Baby ships. Baby huts. Villages too small to map. The world shows its flesh. Big blue pockets around its hips. Gravity gone. Love might be a cheetah, a diamond taunts, and I scream, scaring Miss Browne at the window, asking if I need another notebook.

DAY 10:

Everything crackles inside me. I could be made of lightning. A dying bird beats against my brain.

Swoops between my ears, pecking songs Mama sang me. It makes the notes bleed between my legs, and I cut the gold-and-green dress into beautiful rags to catch the falling sounds.

A trail of ants un-build the rice ships I stranded in the Sargasso Sea and return them to the Atlantic. I set the ghost ship with the twenty transparent sails among them. The trade winds will send it in search of slavers.

On one of Miss Browne’s postcards a woman flowers from an enormous pink-and-white cake. Her waist is very small and her teeth very large. Her arms are flung in the air, her legs and hips buried in frosting. In one hand, a big balloon says: Happy Birthday! I hold it up to Miss Browne and tell her I’ll be 16 in 80 days.

She says there is a book about a man flying a balloon around the world in 80 days. She draws a picture of that balloon, folds it into an airplane, and flies it through the window. I tell Miss Browne that on the man’s 75th day afloat, he might have soared over my ghost ship as it converged on the Feloz. If I can describe what he saw, she’ll give me credit for the test I missed.

I close my eyes and search for page 379 in my history book. Huge black kettles steam on the Feloz‘s bow. Five slavers swivel an enormous cannon mounted on a circle of iron and aim at the ghost ship.

The seasick girl hears two whooshes overhead. The overseer’s whip cracks. The hatches slam closed. Darkness chokes off her air. There was a time before today she thought she’d live forever.

DAY 11:

When the fever breaks the jungle clock will unborn Charles Taylor.

The boys he kidnapped will forget they killed.

The girls he stole will dance again.

Earth’s blue pockets will save the seasick girl.

Foreheads will sing.

Diamonds will become drummers.

Skin will become fabric.

Bush babies will teach history.

Cheetahs will be motorcycles.

Words will outweigh meteors.

Mama will return.

DAY 12:

If I move, I’ll catch fire. Baby Palm Rat won’t come near me. It’s scared I’ll singe its fur. The back of me squeezes the front of me. My space inside is gone. A bush baby must have braided the Feloz‘s anchor in my hair. My head is the cannonball fired over its bow. The whoosh heard by the seasick girl, hot metal gouging raw air.

My head is an egg stuck inside a hen. There are voices inside me. This is how the people who live in Miss Browne’s medieval map must sound. Crazy. And mean. I beg Baby Palm Rat to bring me some water, but it shreds what’s left of Yarn Baby. It eats so much yarn it’ll poop its own yarn baby tomorrow, a yarn baby big enough to smother Germany.

The voices shout WAKE UP! EAT!

A steady rain flows over me. Miss Browne stands on a chair outside the window in her blue rubber gloves. A palm frond stretches from her to me. Dwe pours jug after jug of water down the frond until a river runs from my arms and floods what’s left of the village I built in Mama’s hole.

The seasick girl cries out, Viva.

Baby Palm Rat comes to drink at Lake Mama. Its tongue is yarn-baby red. I submerge my fingers in the water. The fire leaks from me into Lake Mama’s big blue pocket. Dwe’s face swims at the window. His teeth are happy to see me.

DAY 13:

Baby Palm Rat has taught itself how to do back flips. Watching it is better than music. The notes flow slower between my legs at sunset. Hawa walks past and sings: You and me and me and you together are strong. You and me and me and you together are one.

Miss Browne stops at the window and calls Hawa a beautiful songbird. Her voice is so loud it can break open words. Her hands are full of Grade 9 exams. The national test is in 8 days. She begs me to eat some rice. I beg her to tell me more about the Feloz. She reads from Reverend Walsh’s account of the Feloz’s interception by the British Navy. His words bloom in her mouth.

As soon as the poor creatures saw us looking down at them, their dark visages brightened up. They perceived something of sympathy and kindness in our looks, which they had not been accustomed to, and immediately began to shout and clap their hands. One or two had picked up a few Portuguese words, and cried out “Viva! Viva!” They knew we were come to liberate them.

The seasick girl was branded under the breast with a red-hot iron. The air on deck cools her raw skin. Her tongue tastes water again.

DAY 14:

Mama floats through the window and lays her cool hand on my forehead. She sings Baby Palm Rat and me to sleep. When we wake, a new red yarn baby lies on the shore of Lake Mama.

Hawa visits in her slit-eyed deangle mask. It’s like listening to an ancestor. When she laughs, the deangle mask shakes its head no. The rain makes it look as if the mask is crying. Everyone is studying for Grade 9 exams. Hawa tells me soldiers patrol the jungle and roads. The other country five minutes from here is full of Ebola. Our chief says no one can come. No one can go.

She wants to know the yarn baby’s and palm rat’s names. Yarn Baby and Baby Palm Rat, I tell her. I am a terrible mother.

DAY 15:

Deep inside the history book left in the blue bucket, someone wrote a confession in the margin. They must have drunk palm wine laced with gunpowder. It starts above a photo of Desmond Tutu and Nelson Mandela, the one where they hold hands in the air. The confession curves around their heads and snakes down the page.

felicia

come last

friday from

bush school

straight to

chocolate city

belly full of

dumboy we

soak our

tongue with

palm wine

i satisfy

her fish

she stop

five days

i write the

letter

collect

the dowry

give her

kola nuts

and

plenty

a white

chicken

she try to

steal my

gold it

make me

so mad

it just

happen

knife too

sharp

palm wine

too thick

i make

mistake

for true-o

DAY 16:

Someone comes to me in the night. It must be Felicia’s ghost. I write Obi and Esther’s names in the dirt where they slept to hold part of them here. Miss Browne always says that we are living history. That what befalls falls. I throw her postcards around the hut until the floor is a sea of rectangles. I hop from train station to train station, cruise ship to cruise ship. I stomp on a place called Piccadilly. Walk on tiptoe from Jakarta to Rome. What was left of the village I built for Baby Palm Rat evaporates with Lake Mama.

Spread across the hut, the postcards map this world. I tear out the confession and lay it on the Sistine Chapel. If I circle it enough, the name of Felicia’s killer will enter my feet through God’s finger. On the postcards, there are lots of statues with breasts but no heads, or heads but no arms. Maybe Charles Taylor and General Butt Naked made their boy army worship pictures like these before giving them machetes.

Felicia and I were near the old cassava patch when General Butt Naked came through with his boys. She buried me under leaves then hid up a tree. I peed myself as Butt Naked dragged off Dwe’s cousins. Miss Browne said, never forget that day. Everyone else said, forget.

I can feel Felicia’s killer up in Dwe’s coconut palm. How many nights has he waited for me to read his confession? Each circle I make around God’s finger, I see his hunched shadow between the fronds. Whoever it is, has on a wooden Dan bird mask. He wants me to know he’s crossed the boundary between the human and spirit realm.

I crouch in the moonlight licking imaginary knots from my fur. There are plenty of boundaries to cross, plenty of spirits to quarter inside me. Let him think I am not who I am. That I am the seasick girl come back as a lion.

Mama,

Crawl through his dreams and shake him loose.

DAY 17:

Mama leans into me and releases her memory. My spirit is now part cheetah, part thorn. Felicia’s killer thinks I don’t know he climbed down before dawn. He thinks the boundary between realms makes him invisible and quiet, but he is louder than the Feloz‘s cannon.

Baby Palm Rat and I wait for night near the Sistine Chapel. Yarn Baby perches in the window where I put her to keep watch. Her red body turns purple then black at sunset. She is like a red antelope covered in mud. Baby Palm Rat won’t leave my side. I still can’t tell if it is a he or a she, so I think of it as both. We share each other’s sleep. Last night I walked upside down on the ceiling and Baby Palm Rat sang Mama’s favorite song. Felicia’s killer will have to confront what we’ve become. Feral. Unknown.

Yarn Baby trembles in the wind. Felicia’s killer is back. He is a masked snake, slithering up the tree. His body bends at strange angles. His bones are getting softer. Soon his flesh will have no choice but to fall away. Is he counting days? Waiting to see if the sun will touch me again?

DAY 18:

Mama,

When the ambulance men took you, your hair beads left a wavy trail in the dirt. Three snakes splitting your path. I thought that meant you’d come home. Now I know you are gone and already returned to me. You are Yarn Baby and Baby Palm Rat. The seasick girl and the braided village. Cheetahs and bush babies. Sharp and still. The machete that never needs to cut.

Rain punctures the night to feed the ground. The killer’s bones are giving way. Things slide out from under him. Slick feet and hands can’t keep hold long. Soon he will lose history.

DAY 19:

Miss Browne shouts my name over and over until I crawl to her. She points a white gun at my forehead. A soldier at the border to the other country points the gun at everyone before he’ll talk to them she says. He let Miss Browne borrow it for ten minutes. The red number flashes 100. If this were my Grade 9 exam, I’d have a perfect score. Miss Browne laughs and tells me she doesn’t want me to have a perfect score, but she’s happy it’s a lower score than yesterday.

Something is wrong. Miss Browne has never pointed the white gun at my forehead before today.

Mama once told me people try to reach something inside other people that they can’t. Is Miss Browne reaching? Is that why I’m shaking in there? Shadows slip around me. Mama’s hair beads scatter between my ears. I hold up the history book confession to the window. Miss Browne won’t shut up. I want her to read the confession, but she reels off numbers: 104.6. 103.9. 103.1. 102.7. 101.8. 102.4. That’s how many times she’s pointed the white gun at my forehead.

Baby Palm Rat stands between my feet, screeching. Baby is mad at Miss Browne. I am mad at Miss Browne. She says I slept for two days. That I wouldn’t wake up. That I scared her. Her blue rubber fingers fly in the air and drop the white gun.

I describe Felicia’s killer in the palm tree. His sticky climbing feet. His Dan bird mask. His dissolving bones. I’m scared the cheetahs are eating Felicia gone. She saved me from General Butt Naked. I want to find her while she still has a face.

Miss Browne stabs a blue finger at the confession. She is trying to reach my rage, Mama. I think she wants to steal the seasick girl from where I’ve hidden her. But she’s held too deep. Miss Browne will never find her. Between the seasick girl and her there is an ocean. Miss Browne always says history is the long neck of time. My neck is too long to climb.

Miss Browne folds her blue arms. Says she recognizes the writing and I should too. She sounds angry. Baby Palm Rat cowers between my toes. It doesn’t understand what’s happening. Neither do I. My insides feel full of unraveling braids. Villages long gone. There are dark circles circling darker circles the way buyers circle slaves. The way stars circle nowhere they can see. I beg Miss Browne to find Felicia before her face is gone.

I’m falling toward something red and wet. I’m so hungry my stomach could be thunder. A bush baby has lost my dreams. I cry out Mama and feel ice drip inside me. Something is thawing. Another thing burning. Miss Browne says she forgives me. She holds her blue thumb and forefinger together so there’s no air between them and explains that one finger is life, the other death. A drop of water couldn’t squeeze through.

Miss Browne knows people so near death they imagined friends a continent away sitting beside them while they fevered. She tells me that I didn’t want to get lost to history forever, so I brought history here. I needed an anchor to stay. Without it, I would’ve died. She is proud of my imagination. Proud of the confession I wrote. She thinks my pencil was dipped in palm wine and gunpowder.

Dwe runs past, playing “Who Is in the Garden.” His red T-shirt leaves streaks in the air. He is like sunrise and sunset all at once.

I dress Yarn Baby in the history book confession until she looks like an Egyptian mummy. Baby Palm Rat doesn’t recognize her. Today I see two small sacks drop between his back legs. It’s time to cut the Feloz out of the history book and snip its prow. Viva, I cry, as the seasick girl is set free for the last time.

DAY 20:

On the back of empty postcards I write one sentence each: My first history.

This is growing up.

When my oar goes in our river, I want it to ripple continents.

Next time I battle with stones, I’ll know how to forgive.

When my skin dances it will be time to change.

Obi and Esther are my passage to somewhere.

Papa may never know who I really am.

I could be something other than me.

Map everything I don’t know.

Play “Who Is in the Garden.”

Let myself be caught.

DAY 21:

Dwe pulls out the nails in the bar across the window. Hawa takes off her deangle mask and shows me her new tattoo, a songbird with braids. Miss Browne brings Felicia home from Bush School. They put a clean dress in the blue bucket and aim the white gun at my forehead one last time. It’s not a perfect score. Miss Browne reminds me tomorrow is Grade 9 exams. Now it’s time to get 100.

Yarn Baby and Baby Palm Rat watch me fill Mama’s hole with my postcard history. We picnic on the shore of dry Lake Mama. With the leftover rice I christen them Yewande Bakko and Boe Peter Retta. Then I show them how to count to 21.