Elana Levine

Legitimating Television: The Striving Soap Opera

Across American culture and much of the rest of the world, the early 21st century has more and more frequently been seen as a “new golden age” for television. Cultural commentators and everyday viewers regularly note all of the impressive and involving series available across numerous channels and viewing platforms, a circumstance often understood as phenomenal, given the historical status of television as a much less esteemed cultural space. As New York Times writer David Carr noted in 2014, “The vast wasteland of television has been replaced by an excess of excellence.”1

In our book, Legitimating Television: Media Convergence and Cultural Status, Michael Z. Newman and I have identified the discourses at work in this understanding of television as those of cultural legitimation, a process wherein the status of American television has risen, giving the medium, its creative workers, and its audience a new degree of cachet.2 But we also assert that the recent prestige of television depends upon particular premises that ultimately perpetuate a less favorable image for the medium. The legitimation of television in the convergence era depends upon the denigration of so-called ordinary television associated with the past, suggesting that only certain forms, technologies, and experiences of television are worthy of respect and validation. As a result, discourses of legitimation are also elitist and masculinist, in that they employ cultural hierarchies that value those forms and experiences of television typically associated with elite classes and/or with men, and contrast that version of television with the programs and engagements with the medium associated with mass audiences of lower class status and with feminized social groups, such as children, the elderly, and women.

We have analyzed this increased respectability across a number of sites, including the reputations of the series creator- producers known as “showrunners,” the discussion of new viewing technologies, such as high-definition sets, digital video recorders, and streaming services, and the narrative, sound, and visual styles of particular TV genres. In our analysis of the high cultural status of the contemporary serialized prime-time drama series, we consider the ways these programs are figured in production and reception discourse, as well as in their narrative construction, in opposition to soap opera, the original site of serialized drama on US commercial television. Due to the association of daytime soap opera in particular with the feminized sphere of domesticity and the denigrated qualities of emotional excess and convoluted narration, the prestige dramas of prime time TV’s “new golden age” are regularly figured in opposition to this foundational genre. Daytime drama is regularly diminished in the discourse of 21st century prime-time serialization, serving as the other against which the legitimated programming of prime time is distinguished, accruing to it a more elite and masculinized status. As feminist critic Tania Modleski wrote presciently in an earlier cultural age, “In the same way that men are often concerned to show that what they are, above all, is not women, not ‘feminine,’ so television programs and movies will, surprisingly often, tell us that they are not soap operas.”3

Given the disavowal of soap opera in the 21st-century respectability of American television, my current work seeks to challenge the masculinism, elitism, and presentism of such discourse by historicizing US daytime soap opera, demonstrating the variation over time in a genre that was, for most of its history, the economic centerpiece of the US broadcast network business model. Here, I share one thread of that history by considering the ways that US daytime soap opera has itself striven for legitimation and prestige, even repeating some of the masculinist elitism that has long been used to disparage the genre. In particular, my analysis focuses on the guest appearances of feature film actor James Franco on the daytime drama, General Hospital, between 2009 and 2012. The case of soap opera illustrates how even delegitimated culture seeks to improve its status, ultimately reifying the gendered and classed assumptions that underlay cultural hierarchies in the first place.

LEGITIMATION IN US DAYTIME SOAP OPERA HISTORY

As US daytime soap operas transitioned from radio to television in the 1950s, they retained their strong association with housewives, assumed to be their primary audience and, as a result, retained their cultural reputation as mindless entertainment to be consumed as the woman goes about her household chores. Television soap opera quickly became economically profitable for the TV networks and the programs’ sponsors, but its culturally low reputation remained intact. Indeed, when best-selling author Philip Wylie updated his misogynist Generation of Vipers in 1955, he noted that one might simply replace his earlier claims about radio—primarily focused on radio soap operas—with television. He blamed the nation’s “moms”—and the cultural products associated with them—for the downfall of the American character: “I have forced myself to sit a whole morning listening to the soap operas, along with twenty million moms who were busy sweeping dust under carpets while planning to drown their progeny in honey or bash in their heads. This filthy and indecent abomination . . . is now the national saga.”4

Despite the dismissive and disdainful characterization of soap opera as mass, feminized culture, manipulating consumers into household purchases, by the late 1960s the genre started to shift its cultural standing. Younger, unmarried, and male audiences began to be interested in some daytime soaps. ABC’s Dark Shadows, which ran between 1966 and 1971, became a cult sensation, spawning merchandise and feature film spin-offs. Meanwhile, New York- based actors, directors, and other production personnel accrued some respectability for their connections to the Broadway stage and for providing the last bastion of live television drama. In 1971 playwright Harding Lemay, also the author of a memoir nominated for the National Book Award, became the head writer of the daytime soap Another World, bringing the prestige and legitimacy of his reputation to what was widely regarded as a literate and sophisticated period in the program’s history.5 Also in the early 1970s, a number of new soaps debuted, many of them featuring young casts, attention to present-day social issues, and more sexual openness than had been seen previously in the genre. The popular press documented the growing interest in soaps amongst unexpected groups–including men, celebrities, and intellectuals, such as college instructors who began offering courses on the genre, appealing to one of the soaps’ fastest growing sets of fans— college students. As one male student told the New York Times in 1974, “It was a sense of your stuff being on TV for the first time.”6

By the end of the 1970s, the growing respectability of soap opera led to a shift in the genre’s cultural status. At this time, ABC hired a new producer for its longest-running, yet ratings-challenged, soap, General Hospital. Gloria Monty sought to contract actor Anthony Geary to portray the new character of Luke, but Geary reportedly told her, “I hate soap opera,” to which she purportedly replied, “Honey, so do I. I want you to help me change all that.”7 Even if this exchange is apocryphal, General Hospital’s turn to adventure stories in this era—stories that featured Luke and Laura, the woman he loved, and that mixed genres such as action, comedy, sci-fi, and mafia with conventional soap—drew even more new, and young, viewers to the show, making it “hip to watch soaps.”8 In this period, soaps achieved further economic legitimacy and cultural cachet, if not the aesthetic status the genre began to accrue in the early 1970s.9 Also at this time, the genre’s mainstream visibility made it seem less the terrain of housewives. But the loosening of that historical association also perpetuated a cultural dismissal of feminized domesticity and the purported cultural tastes linked to it, for the “better” soaps of this period were understood as substantively different from those of the imagined past.

Beginning in the later 1980s, the soaps’ audiences, profitability, and cultural profile—their economic legitimacy—began to decline. With, first, a multi-channel and, then, a multi-media universe available to deliver content not only during the day but at any time a viewer might want a “soapy” fix, the soaps began to lose much of their cultural centrality, as well as their economic clout within the TV industry. From a one-time high of nineteen such programs, at this writing there are just four. The precariousness of the soaps within the broadcast network business model became especially clear in the late 2000s, where there were still eight soaps on air. First, CBS canceled the longest-running show in US broadcast history, Guiding Light, which had transitioned to television from radio in 1952; then it announced the end of the second longest-running soap, As the World Turns, which debuted in 1956. As of 2009, ABC still had three soaps, but within a few years two of those would be canceled. It was within this context that feature film actor James Franco approached General Hospital about wanting to play a part on the show.

JAMES FRANCO: SOAP OPERA AND/AS PERFORMANCE ART

With the soap industry well aware of the genre’s precarious state, any program would have been understandably happy to have a young and popular feature film actor guest star, and Franco’s appearances between November 2009 and January 2012 generated impressive publicity for General Hospital. But Franco’s presence brought GH more than simple publicity. Executive producer Jill Farren Phelps claimed that Franco had “legitimized” soap opera, that, “There’s all kinds of people now in the acting community who might be willing to do daytime drama as a job, and I think in some measure James made it very cool.”10 Phelps’ conception of Franco’s impact is revealing of all the soaps’ efforts to improve their cultural standing in the early 2010s, as their very existence was so threatened, and of the cultural striving in which the decades-old genre was still engaged.

How, then, did Franco’s involvement affect these efforts? After much speculation in the popular press, Franco addressed his reasons in a Wall Street Journal piece on the history of performance art. Claiming his role on the soap was an experiment in that tradition, he explained,

I disrupted the audience’s suspension of disbelief, because no matter how far I got into the character, I was going to be perceived as something that doesn’t belong to the incredibly stylized world of soap operas. . . . My hope was for people to ask themselves if soap operas are really that far from entertainment that is considered critically legitimate.11

Franco here acknowledges the power of cultural hierarchies, as he had done previously during an interview in which he talked about reading music journalist Carl Wilson’s book, Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste.12 Wilson grapples with questions of taste and gender, applying Pierre Bourdieu’s insights on processes of cultural distinction.13 These indications of the actor’s perspective, alongside universal reports of his deferential treatment of the General Hospital cast and crew, suggest that his “experiment” with the soap meant no disrespect to the genre and may in fact have been an effort to challenge those hierarchies that perpetually denigrate soaps in favor of other forms of moving-image storytelling.

Intentions aside, however, Franco’s experiment ultimately reproduced cultural hierarchies, denigrating soap opera rather than elevating the cultural status of the genre. This was as much the result of the soap’s creators’ handling of the situation as Franco’s own objectives. In integrating Franco into the show, the program’s creators sought to deny and repress its feminized status as soap; they sought to achieve prestige by leaving the soap legacy in the past. This rejection of the genre appeared in their public discourse and in the integration of Franco into the program itself, and it was a typical strategy during this period of great uncertainty about the genre’s future.

Across the many years of the soaps’ declining popularity, those inside and outside the industry spoke disparagingly about its legacy. As one soap critic described, “The idea that soap opera is something that needs to change in order not to be hated has become deeply embedded in daytime producers’ collective psyche during the past thirty years.”14 Former soap writer Sara Bibel agreed, arguing that there is an “ inferiority complex” among soap producers and writers, as well as the network executives that shape the shows’ fates. “During my career as a soap writer, I encountered people in positions of authority . . . who used the word ‘soapy’ as a pejorative. In interviews, producers and head writers often tout changes they are making in the show as being ‘more like prime-time,’ as if that’s automatically superior.”15 Such thinking has pervaded soap production as well as the broader discourses of television in the contemporary era of legitimation.

The daytime soaps’ struggle for status across the 2000s was evident in the programs themselves as well as in industry discourse. In this period, many soaps experimented with stunt episodes that attracted publicity for their affinities with prime time and their distinction from typical soap fare. In 2006, Guiding Light offered weekly episodes focused exclusively upon one character. In one such episode, police officer, wife, and mother Harley Cooper turned into a superheroine named The Guiding Light as the program interspersed panels from a tie-in comic book.16 In 2007 and 2010, One Life to Live featured all-musical episodes.17 And in 2007, General Hospital devoted several weeks of story to a “real time” plot (in the style of the prime-time series 24) about a hostage crisis.18 GH was known for featuring such stunt episodes across the 2000s—train crashes, fires, cars plowing into carnivals—many of which earned the program Best Daytime Drama Series Emmys thanks to their production virtuosity, a mark of distinction that trumpeted the show’s parallels with more costly prime-time efforts.

The gradual move of daytime soaps to high-definition production during this same period was also articulated to strivings for legitimacy. The first television programs to be produced and distributed in HD were live sports broadcasts, followed by the HD distribution of upscale prime-time dramas like The Sopranos. The CBS soap The Young and the Restless was the first daytime program to be shot in HD, begun remarkably early, in 2001, a move the production staff saw as a signal of their growing status. As executive producer Ed Scott claimed, “It makes me feel like I’m doing a feature… it’s so full and rich, like a movie.”19 Most prime-time network dramas and comedies made the switch by the spring of 2004, but less prestigious genres, portions of the schedule, and channels lagged. Most of the soaps converted to HD between 2009 and 2011—not getting the conversion in this period was, in retrospect, a sign of imminent cancellation.20 When GH began shooting in high definition in 2009, the president of ABC Daytime touted the new “filmic, primetime look,” associating the soap with these more highly valued media forms.21

Changes in the soaps’ credit sequences during the 2000s are also notable as efforts at legitimation. In keeping with prime-time series, a number of soaps began to air producing, directing, and writing credits keyed over the screen during the first act of each episode (as opposed to during closing credits only). A number of soaps also added actors’ names to the opening credits, usually alongside an image of the performer.22 The open acknowledgment of key production and on-screen talent, just as in prime time and feature film, allowed the soaps a greater degree of artistic standing than they had been permitted previously, when this creative labor was subordinated to the fictional narrative. In all of these ways, then, soaps have increasingly sought to distinguish themselves from the disparaged “soap opera” label amidst the improved positioning of television more generally.

In the case of GH, these efforts at distinction also wound their way into the stories that got told. From the mid-1990s until early 2012, the central characters on the GH canvas were mobster Sonny Corinthos and his “enforcer” Jason Morgan. While these characters were popular with many viewers, some fans protested the norms and values highlighted as a result of this emphasis on violent, criminal, and male leads, given the genre’s roots in central female characters and family and romantic drama, qualities that feminist scholars have long seen as key to the soaps’ gendered appeal.23 In soap tradition, Sonny’s and Jason’s “sensitive” and “caring” sides were their most valued characteristics, but these traits were often presented as justification for their violent careers and (at least in Sonny’s case) borderline abusive treatment of women. Fans were quite vocal in finding this both morally and politically offensive.24 Yet stories that centered on the angst of male mobsters—over protecting their territory, over the potential danger their work holds for their loved ones, over the challenges they face leading “normal” lives—brought a degree of masculinized cultural legitimacy not typically associated with soap opera. GH began its tale of the emotionally tortured mobster before The Sopranos even appeared, but the attention and acclaim that series generated lent General Hospital a degree of artistic credibility. Franco’s role on the serial was integrated with this mafia focus, and thus the actor was able to be part of the soap world but to do so within the confines of soapdom’s most masculinized—and culturally respected—space.

Franco made just two requests for his GH character: that he be an artist and that he be crazy. There are many ways in which such parameters might have been executed, but the GH creators decided to make the character a mysterious graffiti and performance artist named Franco who had an obsession with mob enforcer Jason Morgan. Franco’s fascination with Jason is due to Jason’s skill as a killer. Obsessed with death and, we soon learn, a serial killer himself, Franco admires Jason and seeks to emulate his work.

It is not surprising that the show involved Franco with Jason, of all characters. Not only was he central to many masculinized storylines, but his portrayer Steve Burton was popular with fans. Burton also shared a manager, Miles Levy, with the real-life Franco. Burton’s management is telling of his position in the soap world, one that is slightly apart from, if not more highly placed than, that of many other soap actors, who are often managed by agencies specializing in soap talent. Burton’s reputation for refusing to bare his chest and resisting doing love scenes also separated him from categorization as the conventional soap hunk, a status further compounded by his character’s and his show’s association with the masculinized action and mafia genres.

While their shared manager may have made Burton’s central involvement a condition of Franco’s appearance, both actors benefited from the storyline skewing this way, for both actors got to avoid more conventionally feminized and soapy narratives as a result. Burton got to brandish a gun, act tough, and try to stop a psycho from hurting those he loves, a role taken on by many an action hero, while Franco got to engage in a postmodern meta-performance, accruing to himself the elite status of the art world. The choice to make Franco a serial killer went a step beyond the actor’s request to be a crazy artist and involved the character more deeply in the action/mob aspects of the soap. In so doing, the storyline furthered the masculinist focus of these plots.

Yet Franco also injected intimations of queerness into the narrative. The actor has long had a queer star image, which his soap appearance drew upon.25 His character’s obsessive fondness for Jason veered into flirtation, with Franco eager to gain the stoic hit man’s admiration. Another queer element was the inclusion of Franco’s performance artist friend Kalup Linzy in the on-screen world. Described as a “gender manipulator” in analyses of his art, Linzy’s queer performance and video work often references soap opera, which he sees as a formative influence.26 On GH, Linzy sang in a town bar and later presented a spoken-word performance of Franco’s theme song, “Mad World.”

These queer elements might have presented a progressive challenge to the masculinism of GH’s mafia focus, but the distance between the Franco-inspired queerness and the conventions of soap opera kept the disruption from engaging with the genre as a whole or with the specificity of the late-2000s GH in any meaningful way. Linzy’s spoken-word performance aired during the 2010 special episodes that highlighted Franco (the actor’s) artistic aspirations.

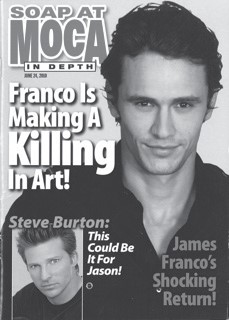

Franco, the character ,exhibited his work at a Museum of Contemporary Art show, titled “Francophrenia,” which was shot on location at MOCA in Los Angeles.27 Franco, the actor, also shot an experimental film during the soap’s location shoot, and got the museum to produce its own version of a soap fan magazine focused on his project.28 While the magazine functioned largely as a promotional venue for Franco’s work on the soap and for the museum itself, it furthered the meta-critical legitimacy of the experiment by linking it to a secondary text so associated with the lowbrow world of fan publications, mimicking the language, layout, and size of a soap fan magazine available in a supermarket checkout line.

These instances of postmodern play serviced Franco’s performance art and broader career but they ultimately remained quite disconnected from the world of soap opera. In the GH narrative, the exhibit turned into a showdown between Franco and Jason, but it was a showdown of no consequence to the broader soap storylines. In effect, the episode hijacked the GH story to showcase Franco’s performance art. It also glamorized the violent masculinity that had become the centerpiece of the character’s arc, and, problematically for many fans, of the 2000s GH more generally.29 The effort to legitimate soap opera through this art frame ultimately serviced Franco’s own aspirations, subordinating the genre’s historically feminized values of meaningfully interconnected stories.30 Franco’s aims aligned in this respect with those of the program’s producers, who were struggling to prove their value in a changed TV climate.

The opportunity Franco provided for queering the 2000s GH was fleeting at best, as his presence had so little consequence for the continuing narrative. The regular GH characters all found Franco to be insane, dangerous, and frightening. Regular viewers necessarily feel an affinity and connection to those continuing characters. Linzy himself acknowledges this in the continuing characters that feature in his own work and in his personal history of investment in a core family of characters on Guiding Light.31 During Franco’s run of brief and intermittent appearances, GH viewers experienced his story through familiar characters’ eyes much more frequently than through Franco’s perspective. As a result, the audience was led to see Franco’s queer presence as harmful and deviant, as further evidence of the character’s villainy. This was only further emphasized when the storyline proceeded to identify Franco as a potential rapist. At one point, Franco is suspected of raping Jason’s wife and, before that, he orders a same-sex rape as an act of revenge against Jason and Sonny, resulting in Sonny’s unjustly imprisoned 18-year-old son being sexually assaulted by a convict named Carter.

This violent framing of Franco’s queer presence would have read quite differently to a viewer that did not regularly watch the soap. From this perspective, Franco seemed to be either mocking or at least challenging the diegetic world in service of a larger artistic mission. Such a viewer would know that Carter is the name of a conceptual artist and filmmaker with whom the real-world Franco had collaborated on the experimental film Erased James Franco and who had explained Franco’s GH role as performance art in the press.32 This explanation, assisted by Carter’s art-world credentials and regardless of the Carter-character’s villainy, helped to legitimate Franco’s decision to appear on the show because it allowed soap opera to be placed back in a low, easy-to-dismiss position wherein Franco could be seen as a quirky yet serious artist, using the soap to his own, higher ends. The GH scenes set at the MOCA exhibit might have read as a challenge to cultural hierarchies that would place soap opera far from the art world. As (real-world) Franco explained of these scenes, “I hope to draw out similarities between all forms of entertainment and art and, hopefully, frame soap operas in such a way that they’ll be seen in a more artistic light.”33 Yet these scenes, and Franco’s GH appearances more generally, ultimately failed to shake up any such cultural hierarchies. In contrast, they ended up reinforcing the denigrated status of soaps because the gestures toward the art world were presented as so foreign to the “normal” narrative world of GH and the character Franco played so violated the terms of the soap’s contract with its feminized audience.

If the real-world Franco had so wanted to disrupt the cultural hierarchies that malign soaps, he might have asked, and the GH producers might have designed, a way to make his appearance organic to the soap’s narrative reality. Franco and the GH team might have demonstrated a true respect for soaps and an effective disruption of the cultural hierarchies that typically diminish them, had they used the attention brought to the show to tell a story well suited to the genre’s history, strengths, and values.34 For instance, Franco might have been a presumed dead character brought back to the canvas, and might have had real familial or romantic ties to legacy characters. Instead, putting a performance art frame around Franco’s soap appearance suggested that soap opera as soap opera is too low a form for an actor like Franco to embrace, so soap opera must be turned into something else in order to make his presence reasonable. In trying to rearticulate soap opera as performance art, General Hospital continued its unfortunate pattern of striving for distinction by rejecting the ever-denigrated category to which it is nonetheless and forever assigned.

CONCLUSION

The cultural legitimation of television in the early 21st century is a well-established phenomenon, one that becomes increasingly integrated into mainstream conceptions of the medium. That said, it is also an historically specific phenomenon. The status of television as an aesthetic and cultural form may be as likely to decline as to further rise in years to come. The case of the shifting cultural status of daytime television soap opera over its history is instructive in this regard. As a genre that has been seen as embodying some of the medium’s most prominent traits, whether in terms of its legacy of commercialism or its ability to tell continuing stories that draw on character histories, soap opera arguably functions as a synecdoche for American commercial television itself.

Yet the historically denigrated status of this genre, rooted in its associations with commercialism, domesticity, and femininity, seems always to return it to a place low in the ranks of cultural hierarchy. The case of James Franco’s guest-starring turn on General Hospital is an especially revealing moment for this tendency. It demonstrates that as hard as those involved in the production of soap opera may try to improve upon its status, such efforts are unable to disrupt the gendered and classed assumptions that have kept soap opera, not to mention American broadcast network television as a whole, from a more secure or prestigious position. The precariousness of the genre and the broadcast system of which it is part instead become more and more evident over time, its economic fragility perhaps also ensuring its ultimate inability to transcend its denigrated place. The story of Franco’s soap-opera stint exposes the harsh realities of cultural legitimation, including the tenuous foundation of privilege upon which it is inevitably built.

1. David Carr, “Barely Keeping Up in TV’s New Golden Age,” New York Times, 9 March, 2014, B1.

2. Michael Z. Newman and Elana Levine, Legitimating Television: Media Convergence and Cultural Status (New York: Routledge, 2012).

3. Tania Modleski, Loving with a Vengeance: Mass Produced Fantasies for Women, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2008), 78.

4. Harding Lemay, Eight Years in Another World (New York: Atheneum, 1981).

5. Philip Wylie, Generation of Vipers (New York: Rinehart, 1955), 214.

6. Fergus M. Bordewich, “Why are college kids in a lather over TV soap operas?” New York Times, 20 Oct. 1974, 157.

7. Robert La Guardia, Soap World (New York: Arbor House Pub. Co., 1983), 181.

8. Jennifer Pendleton, “Hospital right prescription for advertisers,” Variety, 1 April 1993, Special Section.

9. Melissa Scardaville makes this distinction when analyzing soap opera and questions of legitimation. Melissa C. Scardaville, “High Art, No Art: The Economic and Aesthetic Legitimacy of US Soap Operas,” Poetics 37 (2009), 366-382.

10. Jaime Weinman, “Who does James Franco think he is?” Maclean’s, 23 Feb., 2011, http://www.macleans.ca/culture/who-does-james-franco-think-he-is/.

11. James Franco, “A Star, a Soap and the Meaning of Art,” Wall Street Journal, 9 Dec., 2009, http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704107104574

12. “James Franco: Modern Day Renaissance Man,” Fresh Air, 10 Oct., 2010, npr.org.

13. Carl Wilson, Let’s Talk About Love: Why Other People Have Such Bad Taste, 2nd ed. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014). Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge. MA: Harvard UP, 1984). Franco’s connection to Wilson’s work was further cemented when Wilson included an essay by the actor in the second edition of Let’s Talk About Love.

14. Lynn Liccardo, “The Ironic and Convoluted Relationship Between Daytime and Prime Time Soap Operas,” in The Survival of Soap Opera: Transformations for a New Media Era, ed. by Sam Ford, Abigail DeKosnik, and C. Lee Harrington (Jackson, MS: UP of Mississippi, 2011), 120.

15. Sara Bibel, “Deep Soap: Low Self Esteem,” com, 27 May, 2008, http://my.xfinity.com/blogs/tv/2008/05/27/deep-soap-low-self-esteem/.

16. “She’s a Marvel,” Guiding Light, CBS, 1 Nov., 2006.

17. “Prom Night: The Musical,” One Life to Live, ABC, 15-18 June, 2007. “Starr Crossed Lovers,” One Life to Live, ABC, 14 May, 18 May, 2010.

18. General Hospital, ABC, February 2007.

19. Debra Kaufman, “The Young and the Restless: Bringing HD to Daytime Television,” Org, Autumn 2001, 8.

20. One Life to Live switched to 16:9 standard-definition shooting, which eliminated the costly conversion process while seeking the status of the new aspect ratio.

21. Glen Dickson, “High Definition for ‘Hospital,’” Broadcasting & Cable, 6 April, 2009, 3, 6.

22. The Young and the Restless pioneered this in 1999 and continues to do so today, and The Bold & the Beautiful followed in 2005, though it has since stopped the practice. General Hospital began in 2010, but shortened its credit sequence, eliminating actors’ names, more recently.

23. Modleski, Loving with a Vengeance; Charlotte Brunsdon, “Crossroads: Notes on Soap Opera,” in Regarding Television, ed. by E. Ann Kaplan (Los Angeles: American Film Institute, 1983), 76-83.

24. Elana Levine, “’What the hell does TIIC mean?’ Online Content and the Struggle to Save the Soaps,” in The Survival of Soap Opera: Transformations for a New Media Era, ed. by Sam Ford, Abigail DeKosnik, and C. Lee Harrington (Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2011), 201-218.

25. For example, see Evan Real, “James Franco: ‘Yeah, I’m a Little Gay,’” US Weekly, 20 April, 2016, usweekly.com.

26. Nick Stillman, “Kalup Linzy,” BOMB, Summer 2008, http:// bombmagazine.org/article/3143/.

27. General Hospital, 23 and 26 July, 2010, ABC.

28. Francophrenia (Or, Don’t Kill Me, I Know Where the Baby Is), James Franco and Ian Olds, 2012. Soap at MOCA In Depth, 26 June, 2010.

29. Levine, “’What the hell does TIIC mean?’”

30. Robert C. Allen identifies the paradigmatic complexity of soap-opera narrative as a key feature of the genre and the pleasures it offers. Robert C. Allen, Speaking of Soap Operas (Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina Press, 1985).

31. Ibid.; Kalup Linzy, “My Epic Love Affair with the Soap Opera,” Huffington Post, 23 April, 2012, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/kalup-linzy/my-epic-love-affair-with-soaps_b_1444619.html.

32. Erased James Franco, dir. Carter, 2009. Cathy Yan, “Conceptual Artist Carter on James Franco’s General Hospital Appearance: ‘It Was My Idea,’” Wall Street Journal, Dec. 3, 2009, http://blogs.wsj.com/speakeasy/2009/12/03/ conceptual-artist-carter-on-james-francos-general-hospital-appearance-it-was-my-idea/?mod=.

33. Deanna Barnert, “James Franco and the Art of the Soap Opera,” MSN TV, no date, http://tv.msn.com/james-franco-general-hospital/story/ interview/?news=511610&mpc=1.

34. Horace Newcomb has analyzed the ways in which soap opera exemplifies the distinctive narrative potential and pleasure of the American commercial television system. Horace Newcomb, TV: The Most Popular Art (Garden City, NY: Anchor Press, 1974).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, Robert C. Speaking of Soap Operas. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina Press, 1985.

Barnert, Deanna.“James Francoandthe Artofthe Soap Opera.” MSNTV, nodate. http://tv.msn.com/james-franco-general-hospital/story/interview/?news=511610&mpc=1.

Bibel, Sara. “Deep Soap: Low Self Esteem.” Fancast.com. 27 May, 2008. http://my.xfinity.com/blogs/tv/2008/05/27/deep-soap-low-self-esteem/.

Bordewich, Fergus M. “Why are college kids in a lather over TV soap operas?” New York Times, 20 Oct. 1974.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1984.

Brunsdon, Charlotte. “Crossroads: Notes on Soap Opera.” In Regarding Television, edited by E. Ann Kaplan, 76-83. Los Angeles: American Film Institute, 1983.

Carr, David. “Barely Keeping Up in TV’s New Golden Age.” New York Times, 9 March, 2014, B1.

Dickson, Glen. “High Definition for ‘Hospital.’” Broadcasting & Cable, 6 April, 2009.

Franco, James. “A Star, a Soap and the Meaning of Art.” Wall Street Journal, 9 Dec., 2009. http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704107104574570313372878136.

“James Franco: Modern Day Renaissance Man.” Fresh Air. 10 Oct., 2010. npr.org.

Kaufman, Debra. “The Young and the Restless: Bringing HD to Daytime Television.” HighDef.Org, Autumn 2001, 8.

La Guardia, Robert. Soap World. New York: Arbor House Pub. Co., 1983.

Lemay, Harding. Eight Years in Another World. New York: Atheneum, 1981.

Levine, Elana. “’What the hell does TIIC mean?’ Online Content and the Struggle to Save the Soaps.” In The Survival of Soap Opera: Transformations for a New Media Era, edited by Sam Ford, Abigail De Kosnick, and C. Lee Harrington, 201-218. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2011.

Liccardo, Lynn. “The Ironic and Convoluted Relationship Between Daytime and Prime Time Soap Operas.” In The Survival of Soap Opera, edited by Sam Ford, Abigail DeKosnik, and C. Lee Harrington, 119-129. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2011.

Linzy, Kalup. “My Epic Love Affair with the Soap Opera.” Huffington Post, 23 April, 2012. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/kalup-linzy/my-epic-love-affair-with- soaps_b_1444619.html.

Modleski, Tania. Loving with a Vengeance: Mass Produced Fantasies for Women. 2nd edition. New York: Routledge, 2008.

Newcomb, Horace. TV: The Most Popular Art. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press, 1974.

Newman, Michael Z. and Elana Levine. Legitimating Television: Media Convergence and Cultural Status. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Pendleton, Jennifer. “Hospital right prescription for advertisers.” Variety, 1 April 1993, Special Section.

Scardaville, Melissa C. “High Art, No Art: The Economic and Aesthetic Legitimacy of US Soap Operas.” Poetics 37 (2009): 366-382.

Stillman, Nick. “Kalup Linzy.” BOMB, Summer 2008. http://bombmagazine.org/ article/3143/.

Weinman, Jaime. “Who does James Franco think he is?” Maclean’s, 23 Feb., 2011. http://www.macleans.ca/culture/who-dojames-franco-think-he-is/.

Wilson, Carl. Let’s Talk About Love: Why Other People Have Such Bad Taste. 2nd edition. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

Wylie, Philip. Generation of Vipers. New York: Rinehart, 1955.