James F. English

Prestige, Pleasure, and the Data of Cultural Preference: “Quality Signals” in the Age of Superabundance

The economy of literary prestige is undergoing a transition: from the traditional qualitative system of evaluation centered on book reviewing and prize judging, to a now prevalent mixed method system where qualitative reviewing is joined with ratings, rankings, algorithmic predictions, and other quantitative forms of distinction and symbolic hierarchy. Literary studies has been slow to address these new platforms of distinction-making. That is partly because our discipline is inattentive to research in cultural economics, where most of the relevant scholarship has emerged. But it is also because the technology of “personalized taste algorithms,” which have taken so powerful a hold in the domain of screen culture, have yet to gain serious traction among readers of fiction. When it comes to literary consumption, such algorithms are hampered both by the runaway scale of contemporary publishing and by the human labor-intensiveness of the metadata required for their effective functioning. It will likely be a few years before our reading is as synchronized with machine-aided guidance systems as our screen-viewing. In the meantime, as dedicated readers, it is in our interest to understand the complex hybridity of these instruments and to distinguish between inherent limitations of computational distinction-making and deliberate distortions imposed by the culture industry.

i. GREATEST V. FAVORITES

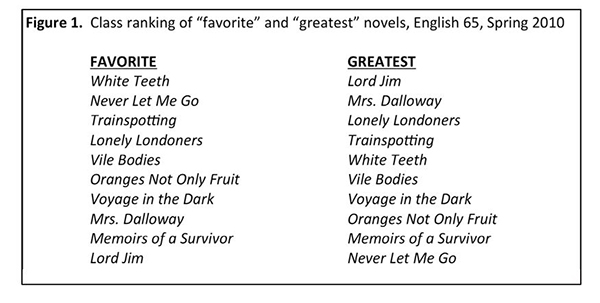

The rating or ranking of works of culture is a longstanding practice, but it involves problems of value and belief with which literary scholars, economists of culture, and corporate taste engineers alike have struggled to come to terms. I have developed a classroom exercise that brings one such problem into particular relief. Whenever I teach a survey of fiction (or also of film), my students are asked in a final assignment to rank the 9 or 10 novels they have read during the term according to: a) which was their favorite, where 1 = favorite and 9 or 10 = least favorite, and b) which is the greatest, where 1 = the greatest novel we read and 9 or 10 = the least great. I don’t define the terms “favorite” or “great” for them or otherwise specify the assignment; they are free to handle it however they like.

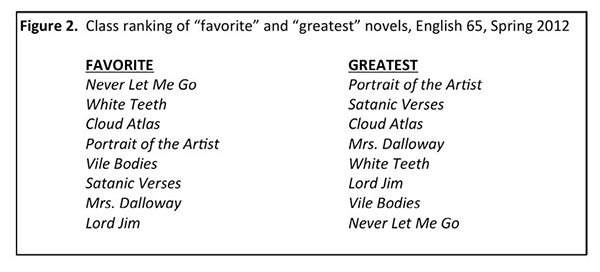

The two lists thus produced are never perfect inversions of each other, but one can always discern in them something of an upside-down logic, with certain texts judged lacking in “greatness” embraced as class favorites, or vice versa. In a 2010 survey, for example, students rated Conrad’s Lord Jim the greatest novel on the syllabus but also their least favorite, while the novel they rated lowest in greatness, Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, was nearly at the top of their favorites list (figure 1). In a class two years later, Ishiguro’s novel had risen to the very top of the favorites scale, while still lying dead last in the hierarchy of greatness (figure 2)

Students do not have difficulty with this assignment. They are basically comfortable operating with two contrary scales of literary value, two ways of distinguishing better novels from worse. As they tend to describe it, these are the scales of affect and of prestige. There are the novels that gave them the most intense pleasure and that they feel most attached to. And there are the novels they regard as reputationally weightiest, most prestigious, most “ important”: the “best” by some other measure or standard, whose legitimacy they do not see as challenged or undermined by its roughly inverse correlation with their felt attachments and enthusiasms.

It is not quite correct to call this other standard “external,” as opposed to an internal or personal standard of positive feelings and pleasures. Both standards derive from large, socially elaborated systems of cultural value-production, systems shaped by gender codes, by racial divisions, by generational differences, and so on. And the rules of these social systems have in both cases been internalized by individual readers. Nor is it entirely correct to view the two systems as corresponding sociologically to opposed class strata, the scale of greatness defining literary value for a culturally well-endowed fraction of society (the “school”; the proper determiners of prestige) and the scale of favorites for a culturally impoverished fraction (the “masses”; the proper determiners of popularity). Whatever fraction of the reading population we might be looking at, and whatever kinds of literature they might prefer, they will understand and consistently deploy both these scales of value, expressing warm attachment to books they do not regard as great, and acknowledging the greatness of books (Pride and Prejudice, say, or Beloved) that they don’t in fact find congenial.

This “perfectly natural” duplicity, this easy relaying within the readerly habitus between contrary scales of value, is not widely acknowledged in literary studies, which traditionally imagined its pedagogical effect and social purpose as supplanting the one set of values with the other. We supposedly drill our students to stop valuing easily assimilated books that afford close identification with a protagonist and deep immersion in an imagined world of event and action, and instead to value difficult books that offer original and challenging problems of language, form, and meaning. Nabokov offered his students at Cornell the classic formulation: “I have tried to make of you good readers,” he told them, readers “who read books not for the infantile purpose of identifying oneself with the characters, and not for the adolescent purpose of learning to live…. I have tried to teach you to read books for the sake of their form, their visions, their art.”1

The discipline’s discontents have felt this training as a loss, an extinguishing of the spontaneous immersive pleasure once afforded by the act of reading. We see something of this lament in Trilling’s critical account of the prevailing literary culture in his 1963 essay “The Fate of Pleasure,” where he suggests that modernism has too unequivocally repudiated aesthetic pleasure, committing to a disproportionate and undialectical aesthetics of difficulty and darkness.2 Through its foundational embrace of the modernist ethos, the New Criticism—”English” as a postwar discipline—institutionalized this repudiation, imposing it as the non-negotiable condition of higher learning. So it is that for Janice Radway, writing a few decades after Trilling, in A Feeling For Books, a radical break was required from established critical method in order to reactivate the capacity to experience readerly pleasure and to value the books that arouse it.3 She had to de-cathect from her academic mentors, who taught her to feel only “intellectual…disdain” (114) for what she calls “the pleasures of imaginative absorption” (76), and especially for her warmly felt identification with a protagonist, her immersive fantasies of participation and connectedness, and for the novice, typically female error of affective fallacy, judging a text by its resonance with her own emotions.

For Radway, training in literary studies was a kind of brainwashing or reprogramming. To acquire properly literary habits of mind you have to unlearn the habits of ordinary reading, “suppress[ing] the desire to read in a less cerebral . . . way” (4). To appreciate the genius of Ulysses you must repudiate the pleasures of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. The all-or-nothing logic of this formulation parallels Pierre Bourdieu’s handling of his concept of the literary illusio.4 The illusio involves unfeigned belief in the specific goal at stake on the field of literary practice, belief in the reality of literary genius, of great masterpieces, and of the pure and timeless value of authentic Art. In Bourdieu’s account, the moment you engage in literary practice, stepping onto the field as an active and functional player, you accept the illusio absolutely. Any hint of skepticism or two-mindedness would undermine the quality of your play—as for a tennis player who, in the midst of a long and difficult match, finds herself uncertain as to the reality of “points,” the desirability of winning them, or the value of athletic pursuits in general.5 This may be quite wrong. I have argued elsewhere that the normal thing is to be both a believer and a disbeliever, that duplicity of this kind, in some degree or ratio, is, at least in our present-day cultural circumstances, difficult, maybe impossible to overcome.6 Such a view is implicit in Rita Felski’s discussion of the aesthetics of pleasure in Uses of Literature.7 Unlike Radway, Felski does not regard the “pleasures of absorption and attachment” as the babies that get tossed out with the bathwater of naïve credulity in the course of acquiring literary expertise. The experience of “total absorption in a text, of intense and enigmatic pleasure” (53)—this is how Felski defines her key category of “enchantment”—this experience survives all manner of academic training. It remains, for us as for “ordinary readers,” fundamental to the phenomenology of reading. It is the basis of our durable attachments to certain authors, certain characters, certain works—our favorites— which may or may not align with what we understand to be the canon of masterworks. A different way to put this is to say that we accept the greater value or prestige of certain works even at the same time that we recognize their prestige as a kind of trick. (Etymologically, prestige derives from prestigium: a juggler’s illusion, prestidigitation, sleight-of-hand). Cultural prestige is a form of collective make-believe from which non-belief, consciousness of trickery, is never entirely absent.

ii. JUDGMENT DEVICES AND ASPIRATIONAL REVIEWERS

This matter of ambivalence or suspension between pleasure and prestige, the reader’s simultaneous interest in personal enjoyment and in some kind of higher artistic standing or critical regard, has mostly been neglected by economists of the arts in their by now fairly extensive research into the use of reviews, ratings, and rankings in the culture industries. Much of this work builds on a distinction first proposed by Philip Nelson between ordinary commodity goods (or “search goods”) and what he termed “experience goods.” The idea is that when we buy something like, say, a ream of printer paper at a CVS or a grocery store, we aren’t much troubled by questions of quality; we just search for the right shelf and item and make our purchase (hence “search good”). “Experience goods” are goods or services whose quality is truly unknown prior to use or consumption: a pair of headphones, a meal in a restaurant, or (the classic example in the economic literature) a bottle of fine wine. These we cannot evaluate until we’ve consumed or “experienced” them.

Of course the distinction is a little problematic (what if I “experience” edge-curling when I use that CVS paper in my printer?). But it’s clear that products of the creative industries such as novels are generally more like experience goods than search goods, in that as consumers of a novel we remain uncertain of its quality prior to reading it, and it may well disappoint or otherwise “surprise” us when we do so. As another economist, Michael Hutter, has argued, surprise is a defining affordance of experience goods.8

Given the variety and abundance of new novels being published (more on this in a moment), it is obviously impractical to consume them at random in hopes of experiencing more good ones than bad. Rather, readers must rely on “quality signals” of various kinds (credibility of the publisher, authorial signature or “brand,” cover design and pricing, sales figures, advertising claims, word of mouth, etc.), and in particular on what the influential economic sociologist Lucien Karpik calls “judgment devices.”9

Work in this area has mainly focused on the sales impacts of favorable or unfavorable judgments made by book reviewers and similar experts in other creative fields, and of cultural prizes and awards. But recently, as you might expect, the research emphasis has shifted to top-10 lists (or top-50, top-100), aggregated online consumer reviews (OCRs), and individuated algorithmically derived recommendations, which rate works according to your imputed standards of enjoyment and excellence, your own preferred ratio of pleasure to prestige, via “personalization algorithms.” For me the key takeaway from these studies is something they don’t explicitly emphasize: that the most effective computational judgment de-vices are those that depend most heavily on the qualitative judgments of established reviewers or other “domain experts,” and, where the fiction market is concerned, on the detailed evaluative work of experienced and respected reviewers, to whose critical opinions readers tend in some measure to defer. Indeed, this habit of deference, as manifest in class rankings by “greatness,” exceeds the whole Nelsonian/Karpikian model of “experience goods” and would require, even within the limited terms of their discipline, some grappling with what economists who research health-care services have called “credence goods.” A credence good is one whose quality the consumer feels underequipped to judge even after consumption; its value is at least partly judged not from experience but through an act of faith, a belief in or crediting of what Karpik calls the “expertise regime.”

The economic literature generally seeks to determine the effectiveness of the new judgment devices in influencing consumer behavior. This is more difficult than you might think. Even in the market for cinema, which presents fewer challenges to empirical research than literature, it is not so easy to make the case that OCRs and algorithms are strong drivers of consumption. For the summer blockbusters, studies show that word of mouth remains the key to ticket sales. And for word of mouth the main technological mediators are not OCR aggregators but simply twitter and messaging apps. For smaller-scale pictures aimed at non- adolescent audiences, per-screen revenue correlates better with traditional quality signals such as prizes and awards and critics’ picks than with the mass-aggregation systems.10 And of these newer devices, a study conducted in 2012 found consumers’ actual levels of support for “quality” films correlated better with the narrower and more stature-weighted critics’ review aggregators Metacritic and Movie Review Intelligence than with the populist “Freshness Meter” scores on Rotten Tomatoes or with any site’s aggregated OCR scores.11 One difference here was that the mixed-methods approaches of Metacritic and Movie Review Intelligence involved a good deal of qualitative, expertise-intensive labor to separate more from less positive reviews and more from less credible reviewers and then to impose a system of weighting. Rotten Tomatoes by contrast simply counted every review, from a lengthy rave in the New York Times to a lukewarm endorsement on a Hollywood fansite, as an equal-sized plus or minus datum.12

You’d think that would mean industry support for the more nuanced and qualititative, expertise-intensive aggregators. But in addition to being more nuanced and challenging to derive, the quality signals of Metacritic or MRI took the form of generally lower—more moderately positive—ratings than the Rotten Tomatoes scores, which have a clear tendency toward grade inflation.13 Industry giants Warner Bros and Comcast have therefore poured money into Rotten Tomatoes while squeezing or killing off Metacritic and MRI (which closed due to lack of financial backing). Something similar has happened at Netflix, whose superb “rating prediction” algorithm has been deliberately blunted in the course of the company’s official shift of emphasis from U.S. DVDs to global streaming.

The Netflix rating predictor considers your “taste profile” in the context of the company’s enormously detailed metadata, and predicts how you would rate any particular movie or program. Here again, traditional judgment devices play a more crucial role than we might expect. The Netflix metadata include a great deal of historical information about the judgments of critics, festival curators, and prize juries, and these figure significantly in the algorithm as “qualities.” Of the twelve prioritized qualities that count toward one’s “taste profile,” half are keyed to critical expertise: Classics; Critically-acclaimed; Emmy Winners; Golden Globe Winners; Oscar Winners; and Sundance Film Festival Winners. Even if you never filled out this part of the “taste preferences” questionnaire (an option that was removed in January 2016),14 the correlations between your tastes, as implied by your viewing and rating habits, and the preferences of specific critics or prize juries or other proxies of the expertise regime are continually computed and used as bases for the personalized recommendations and predicted ratings that appear on your Netflix landing page.

It turns out that these correlations are generally pretty strong. Netflix’s “personalization engineers” agree that it is not just my students but most of their subscribers who operate with two non-parallel scales of cultural value, the more or less official or expertly-determined scale of greatness (“prestige”), and the more or less personal scale of favorites. But, like most OCR aggregators in the creative industries (and in accord with economists who treat the act of cultural consumption as an unmixed experience yielding a simple clear judgment as to “quality”), the Netflix site is built around the idea of a single, “overall” rating. How are we to interpret this combined or amalgamated valuation? If the students in my 2010 British fiction survey had been asked to rank the assigned novels neither by greatness nor by favorite, but “overall,” what would they have done with Lord Jim? With Never Let Me Go? Would both those novels be rated middling? Both rated very high? Or would one scale trump the other?

Netflix’s engineers believe that in fact Lord Jim would prevail, on the principle that “overall” ratings lean deferentially toward the established scale of prestige. And they regard this tilt as statistically misleading, an artifact of people’s tendency to indulge in what the Netflix director of engineering calls “aspirational” reviewing habits.15 As another exec, the VP of Personalization Algorithms, explains: “People tend to rate [critically acclaimed films] very high,” even if most of the time they want to watch films they rate much lower. (His example: a guy who’s always watching “silly comedies like Hot Tub Time Machine” will give these films three stars and rate high-status films like Schindler’s List, which he never watches, five stars.)16 Both kinds of film function on this metric as credence goods, with perceptions of expert opinion weighted more heavily in the final calculus of quality than the viewing experience itself. At any rate, this, according to Netflix management, is why with each new interface the company has made its predictions of films you’d rate highest harder to locate while populating your landing page with films that its taste engines predict you’ll rate just three stars. Trust our calculus, they are saying, you don’t really want to watch all that higher-grade stuff, anyway.

There is another and more salient reason why these less culturally “aspirational” recommendations are blanketing your screen. If Netflix actually told you what ten recent films their algorithms predicted you’d rate the highest, they would be sending you elsewhere than into their own very limited streaming library. Even if you happen to know the titles of those films, and even if you can find the tiny, hidden Netflix search box, searching will in most cases afford you “no matches.”17 Chances are, Netflix does have the films, and rich metadata regarding their production and consumption, but to find them you’d need to subscribe and log in to the company’s now discreet mail-service unit, and deploy that site’s search engine.

When, a few years ago, subscribers began exporting their personal film ratings to Jinni, whose excellent semantic-search Entertainment Genome put those ratings to work in a vendor-neutral algorithm, Netflix blocked users’ access to their own data. Worse still, Jinni withdrew its recommendation engine from the web in 2015, and now only markets its analytics to the major studios and TV networks. Finally, as you know if you’re one of Netflix’s 50 million customers, in the process of thus shielding us from its best “quality signals” and from our own “misleading” bias toward prestige, Netflix is attempting to steer us away from film toward TV. In my case, away from recent movies by Mike Leigh or Steve McQueen toward television shows like Longmire or Madame Secretary (my rating of the latter predicted at only 2 ½ stars).

iii. THE DIFFICULTIES OF LITERARY DATA

Netflix at least has the technical capability to build impressive personalized judgment devices, even if it chooses for commercial reasons to interfere with its own best quality signals. When we turn to the literary websites, the metrics of taste are much more elusive. Nearly two-thirds of Netflix customers chose the last film or TV show they watched based on what Netflix recommended. According to a 2013 study by the Codex Group, barely 10% of Amazon customers who read a lot chose their last book based on any of Amazon’s ratings, recommendations, or search engines.18 The company’s “recommended for you” algorithm drives a negligible share of reader choices.

One reason Amazon is so much less good at this than Netflix is simply the different scales of the film and publishing industries. There were about 800 feature films produced in the U.S. last year, and only a few thousand worldwide. The number of new novels published in the U.S. last year was at least 60,000 in traditional print form and perhaps another 60,000 in non-traditional forms such as self-published, print-on-demand, and e-Book-only. And then there’s the entire back catalog: altogether, the shelves of adult (i.e. non-juvenile) fiction in the Amazon store comprise more than a million books.

Netflix’s enviable metadata includes information about plot, visual effects, goriness, romance levels, moral status of male vs. female characters, sexual suggestiveness, genres and subgenres and sub-subgenres. Alexis Madrigal and Ian Bogost wrote a script to run through the complete set of Netflix “microgenres,” finding that the company has 76,897 unique labels for different types of films and TV shows, ranging from “Emotional Fight-the-System Documentaries” to “Sentimental Set-in-Europe Dramas From the 1970s” and “Time-Travel Movies Starring William Hartnell.”19 Much of this quasi-generic information, and many other bits of data as well, are hand-gathered, entered into elaborate spreadsheets by teams of employees, mostly aspiring screenwriters and movie buffs, who watch and research the films and record the tags. With a few dozen new feature films and TV shows entering the Netflix library each week, this is a large but manageable task.

To assemble comparable information pertaining to novels would take much longer per text, and even if you could somehow gather metadata for the million novels already in the library, you’d have to contend with new books flooding in at the rate of one every five minutes, hundreds a day, thousands per week. This is just the fiction, remember, which holds no special importance for Amazon; the company would have to undertake this task for the much larger nonfiction section as well.

Some of the challenges of data collection on this scale could be obviated by focusing on only the books that actually have readers besides mom and a couple of friends from work—the ones that have sold, say, 200 copies. That would actually eliminate about three- quarters of all novels. But to produce a judgment system comparable to Netflix’s “hybrid human and machine intelligence,”20 you would still need to employ an army of actual fiction readers, literary domain experts, to do a great deal of qualitative work involving many subtle judgments and informed decisions of classification. Amazon, as we know, prefers to keep its human workforce as small, as nearly automated, and as minimally compensated as possible. But textual data of the kind that can be extracted without heavy involvement of domain experts can only provide an impoverished basis for generating quality signals.

Reliable algorithmic rating systems like Netflix’s or Jinni’s have to coordinate the textual metadata with data on consumer preferences, and Amazon is struggling in that respect as well. Unlike Netflix, which prompts you at the login to say whether it’s you or someone else in the household who will be viewing, Amazon cannot effectively distinguish between print books you purchase for yourself and print books you purchase as gifts. And while the company sells a mountain of books, only a tiny fraction of its customers—generally less than 3%—bothers to rate or review them. Scholars who propose, perhaps too naively, treating Amazon’s consumer reviews as a great trove of information about popular reading habits and the rise of amateur criticism have seized on bestsellers like Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner or David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest as their case studies.21 But these are the exceptions that prove the rule of Amazon’s paltry OCR content. Consider a novel with good but non-stratospheric sales numbers. Ben Lerner’s debut novel of 2011, Leaving the Atocha Station, was a surprise hit with readers, appearing on dozens of top-ten lists and major prize shortlists and selling tens of thousands of copies. There are barely a hundred OCRs on Amazon. Fewer still are available for How to Be Both (2014), the stunning and widely honored sixth novel of Britain’s Ali Smith. The “average rating” in such cases isn’t statistically meaningful. The situation contrasts sharply with that of Netflix, where films routinely have a million or more ratings. Even a modestly budgeted European coproduction like 2011’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy has more than 750,000.

My examples here, Leaving the Atocha Station and How to be Both, are exceptionally successful books, on their way to becoming “contemporary classics.” Most of the novels other than bestsellers that are available from Amazon have nowhere close to 100 reviews. The most recent novel by Geoff Nicholson, a British writer I sometimes teach, has 14 reviews. His brilliantly funny 1998 novel, Bleeding London, has 10 reviews and an average rating of 4.2 stars. Numbers like these, and they are typical, mean that just a couple of 1-star, 1-line hatchet jobs—or 5-star reviews from family members—can completely skew the aggregate rating. It’s just too easy to game this system, especially given that a resounding verdict from early reviewers, positive or negative, can have durable knock-on effects. Amazon has instituted a series of policies designed to prevent authors from engaging in “sockpuppetry” (5-starring themselves under multiple assumed login IDs), contracting with “review factories” to produce positive reviews from authentic-looking Amazon customers, or sabotaging the competition by planting negative reviews of their books. But these are widespread practices, which even some well-known authors have admitted to, and which you will find recommended as sound self-marketing strategies for aspiring Indie authors on blogs like Stephen Leather’s “How to Make a Million Dollars From Writing eBooks,” or in eBooks like Michael Alvear’s Make a Killing on Kindle (which describes exactly how to place the kind of “strategic starter reviews that give browsers permission to buy”).22

In short, Amazon’s efforts to quantify and automate the process of literary evaluation have been hampered by too much bad data and too little good data on both sides of the spreadsheet, the text side and the reader side, especially when considered in relation to the enormous scale of 21st-century publishing. The company cannot even begin to assess such subtle factors as “aspirational” tendencies in rating habits, or to set individuated ratios of experience (of pleasure) vs. credence (in the economy of prestige) in weighting the data for its users.

Readers do sometimes credit Amazon’s “quality signals,” choosing a book based on what they learn on amazon.com; as I mentioned, among regular readers who shop on the site, this accounts for about 10% of their reading. But that’s not very good, and Amazon knows it, which is one reason why in 2013 they bought Goodreads, whose users are three times more likely to rely on it for literary guidance. These figures come from the Codex Group, a New York firm specializing in book audience research. According to their 2013 study, the only online resources that succeed better in steering visitors to the next book they will read are dedicated author sites. And those comprise a very different online neighborhood since their denizens are loyal fan communities, bound together by relatively similar reading habits. Compared to Amazon, visitors on the Goodreads site are not only three times more likely to find their way to their next book there, they are also many times more likely to rate the books they read and/or to review them qualitatively, and, based on my own quick and admittedly crude sample of wordcounts, their reviews are on average nearly twice as long as Amazon reviews. Added to this, the average Goodreads user reads two to three times as many books per year as even the average “regular reader” among Amazon users.23 To return to our example of Lerner’s novel, on Goodreads there are 800 written reviews of Leaving the Atocha Station and nearly 6,000 ratings, fifty times as many as on Amazon. A novel like Never Let Me Go can have a quarter-million ratings and 20,000 reviews. Fifty Shades of Grey has more than a million ratings and 70,000 written reviews (approaching Netflix territory).

Goodreads is a “social collection” or “social curation” site. Users construct personal libraries of books they’ve read, are currently reading, or are thinking of reading in the future. They can click through to the ratings and reviews of any of these books, rate the reviews they read, explore the complete libraries of reviewers they come to trust, solicit recommendations from particular readers, pass those recommendations on to others, or offer recommendations of their own. By aggregating and mining these evaluative decisions, Goodreads constructs its own ranked lists of books with certain shared characteristics of form and reception, which it then recommends. (Recommended for James: “Favorite Novels About Professors or Academics.”) Goodreads, not Amazon, is the online meeting hall for those whom Jonathan Franzen (author of The Corrections, #38 on “Favorite Novels About Professors or Academics”) called the “open-minded but essentially untrained fiction readers.”24 Not, that is, the Professors or Academics, but a larger and more heterogeneous cohort that is the crucial demographic for purposes of literary data gathering. As the NEA discovered a decade ago in their much-publicized national research report on reading, only about half of Americans read even one book a year not required for work or school.25 Codex Group’s latest study shows that 80% of all the reading in America is done by only 19% of the adult population.26 80% of the fiction reading is done by about 9% of Americans. And just a tenth of those avid fiction readers, less than 1% of the population, writes the lion’s share of all the tens of millions of online fiction reviews.

Those are Goodreads’ readers, and they are the kind of domain experts whose qualitative input is needed to support credible online platforms of literary judgment. If we want to see development of those platforms in the reasonably near term, we could look optimistically upon Amazon’s acquisition of Goodreads. For less than 200 million dollars, the company purchased what it was unable to produce internally: a large-scale network of serious readers and their readings with the attendant metadata. Less optimistically, we might consider how commercial interests have led to systematic degradation of the quality-signaling system at Netflix, and worry that Goodreads will see its utility as a shared space of discovery and assessment eroded as its architecture is redrawn to maximize shelf space for Kindle Direct and the rest of Amazon’s growing stable of house-brand literature.27

1. Vladimir Nabokov, Lectures on Literature (New York: Harvest, 1980), 381-82.

2. Lionel Trilling, “The Fate of Pleasure,” Partisan Review (Spring 1963): 167-191.

3. Janice Radway, A Feeling for Books: The Book of the Month Club, Literary Taste, and Middle-Class Desire (Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 1997).

4. Pierre Bourdieu, The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field, Susan Emanuel (Stanford: Stanford UP, 1997), 227-28.

5. Bourdieu does allow that this double-mindedness may be possible, but only in the most extreme cases of reflexive literariness, “the case of a poetry which has achieved self-awareness,” such as that of Mallarmé. See Bourdieu, “The Impious Dismantling of the Fiction,” in Rules of Art, 274-77; quotation from 275.

6. James English, The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2005), 375, n. 40.

7. Rita Felski, Uses of Literature (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008).

8. Michael Hutter, “Infinite Surprises: On the Stabilization of Value in the Creative Industries.” In The Worth of Goods: Valuation and Pricing in the Economy, ed. by Patrik Appers and Jens Beckert (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2011), 201-222.

9. Lucien Karpik, Valuing the Unique: The Economics of Singularities (Princeton: Princeton UP, 2010), 44-54.

10. See the discussion of Max Woolf, whose recent statistical analyses and contour visualizations, published on his excellent minimaxir site, capture a strong correlation cluster for well-reviewed quality films with less than mass appeal. Max Woolf, “Movie Review Aggregator Ratings Have No Relationship with Boxoffice Success,” minimaxir.com, January 2016, http://minimaxir.com/2016/01/movie-revenue-ratings.

11. Joshua L. Weinstein, “Rotten Tomatoes, Metacritic, Movie Review Intelligence,” The Wrap, 17 Feb. 2012, accessed 25 May 2016, https://www.yahoo.com/movies/rotten-tomatoes-metacritic-movie-review-intelligence-152627564.

12. Rotten Tomatoes has since tightened up its criteria of eligibility to be counted as a critic in its Freshness Meter. For its current requirements, see “Tomatometer Criteria” on the website at https://www.rottentomatoes.com/help_desk/critics/.

13. See slide 2 in Weinstein, “Rotten Tomatoes.” While Rotten Tomatoes tends to inflate good grades relative to the other sites, scoring many more films in the 90s, it also imposes relatively harsher low grades. The more recent analysis by Woolf (minimaxir) finds no overall positive correlation between the Freshness Meter, or any of today’s leading review aggregators, and actual consumer behavior.

14. The entire “Taste Preferences” section of the Netflix site was taken down at the start of 2016, but the company presumably continues to incorporate into its algorithms these correlations between an individual user’s tastes and the values imposed by major instruments and institutions of the expertise regime.

15. Tom Vanderbilt, “The Science Behind the Netflix Algorithms that Decide What You’ll Watch Next,” Wired, 7 August 2013, http://www.wired.com/2013/08/qq_netflix-algorithm.

16. Vanderbilt, “The Science Behind the Netflix Algorithms.”

17. Part of the transition from the DVD-by-mail to the streaming business model has been Netflix’s positioning of itself as a “recommendation company,” as opposed to a “search company” such as eBay.

18. See the Codex Group chart entitled “Digital Media Visited Last Week vs. Discovery Share Last Book Bought,” in Laura Owen, “Why Online Book Discovery is Broken (And How to Fix It),” Gigaom online, 17 January 2013. https://gigaom.com/2013/01/17/why-online-book-discovery-is-broken-and-how-to-fix-it/.

19. Alexis C. Madrigal, “How Netflix Reverse Engineered Hollywood,” The Atlantic, 2 January 2014, http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/01/how-netflix-reverse-engineered-hollywood/282679/. Ian Bogost, “Reverse Engineering Netflix” (paper delivered at Bot Summit 2014 and posted to the conference archives in OpenTranscripts, 29 May 2015), http://opentranscripts.org/transcript/reverse-engineering-netflix. The authors note that Netflix officially refers to these classifications as “altgenres.”

20. Madrigal, “How Netflix Reverse Engineered.”

21. Timothy Aubry, Reading as Therapy: What Contemporary Fiction Does for Middle-Class Americans (Iowa City: U of Iowa Press, 2011); Ed Finn, “Becoming Yourself: The Afterlife of Reception,” Stanford Literary Lab, Pamphlet 3, 15 September 2011.

22. Michael Alvear, Make a Killing on Kindle: The Guerilla Marketer’s Guide to Selling Your E-Books on Amazon (Amazon Digital: 2012), chapter 12.

23. Most of my statistics on Goodreads and Amazon come from Codex Group, as reported by Jordan Weissmann, “The Simple Reason Why Goodreads is So Valuable to Amazon,” The Atlantic, 1 April http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2013/04/the-simple-reason-why-goodreads-is-so-valuable-to-amazon/274548/.

24. Christopher Connery and Jonathan Franzen, “The Liberal Form: An Interview with Jonathan Franzen,” boundary 2 36.2 (2009): 34, qtd. in Seth Studer and Ichiro Takayoshi, “Franzen and the ‘Open-Minded but Essentially Untrained Fiction Reader,’” Post45, 8 July 2013. http://post45.research.yale.edu/2013/07/franzen-and-the-open-minded-but-essentially-untrained-fiction-reader/.

25. National Endowment for the Arts, Reading at Risk: A Survey of Literary Reading in America, Research Division Report #46, June 2004, ix. The NEA’s subsequent report, Reading on the Rise: A New Chapter on American Literacy (2009), made much of a slight increase of this figure, from 47% to 50%.

26. Weissmann, “The Simple ”

27. On Amazon’s current role as a publisher (rather than simply a retailer) of fiction, see Mark McGurl, “Everything and Less: Fiction in the Age of Amazon,” Modern Language Quarterly 3 (2016): 447-471.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alvear, Michael. Make a Killing on Kindle: The Guerilla Marketer’s Guide to Selling Your E-Books on Amazon. Amazon Digital: 2012.

Aubry, Timothy. Reading as Therapy: What Contemporary Fiction Does for Middle- Class Americans. Iowa City: U of Iowa Press, 2011.

Bogost, Ian. “Reverse Engineering Netflix.” Paper delivered at Bot Summit 2014 and posted to the conference archives in OpenTranscripts, 29 May 2015. http://opentranscripts.org/transcript/reverse-engineering-netflix.

Bourdieu, Pierre. The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field.

Translated by Susan Emanuel. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1997.

Connery, Christopher and Jonathan Franzen. “The Liberal Form: An Interview with Jonathan Franzen.” boundary 2 36.2 (2009): 34. Quoted in Seth Studer and Ichiro Takayoshi, “Franzen and the ‘Open-Minded but Essentially Untrained Fiction Reader.’” Post45, 8 July 2013. http://post45.research.yale.edu/2013/07/franzen-and-the-open-minded-but-essentially-untrained-fiction-reader/.

English, James F. The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2005: 375, n. 40.

Felski, Rita. Uses of Literature. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

Finn, Ed. “Becoming Yourself: The Afterlife of Reception.” Stanford Literary Lab, Pamphlet 3, 15 September 2011.

Hutter, Michael. “Infinite Surprises: On the Stabilization of Value in the Creative Industries.” In The Worth of Goods: Valuation and Pricing in the Economy, edited by Patrik Appers and Jens Beckert. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2011.

Karpik, Lucien. Valuing the Unique: The Economics of Singularities. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2010.

Madrigal, Alexis C. “How Netflix Reverse Engineered Hollywood.” The Atlantic, 2 January 2014. http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/01/how-netflix-reverse-engineered-hollywood/282679/.

Nabokov, Vladimir. Lectures on Literature. New York: Harvest, 1980.

National Endowment for the Arts. Reading at Risk: A Survey of Literary Reading in America. Research Division Report #46, June 2004.

Owen, Laura. “Why Online Book Discovery is Broken (And How to Fix It).” Gigaom online, 17 January 2013. https://gigaom.com/2013/01/17/why-online-book-discovery-is-broken-and-how-to-fix-it/.

Radway, Janice. A Feeling for Books: The Book of the Month Club, Literary Taste, and Middle-Class Desire. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Trilling, Lionel. “The Fate of Pleasure.” Partisan Review (Spring 1963): 167-191.

Vanderbilt, Tom. “The Science Behind the Netflix Algorithms that Decide What You’ll Watch Next.” Wired, 7 August 2013. http://www.wired.com/2013/08/qq_netflix-algorithm.

Weinstein, Joshua L. “Rotten Tomatoes, Metacritic, Movie Review Intelligence.” The Wrap, 17 February 2012. Accessed 25 May 2016. https://www.yahoo.com/movies/rotten-tomatoes-metacritic-movie-review-intelligence-152627564.html.

Weissmann, Jordan. “The Simple Reason Why Goodreads is So Valuable to Amazon.” The Atlantic, 1 April 2013. http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2013/04/the-simple-reason-why-goodreads-is-so-valuable-to-amazon/274548/.