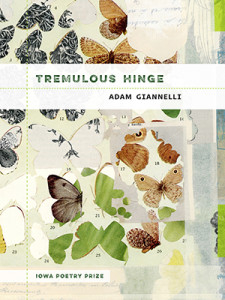

Tremulous Hinge

Adam Giannelli

University of Iowa Press, 2017

Reviewed by Chelsea Dingman

What can language accomplish, in and of itself? In Tremulous Hinge, Adam Giannelli’s award-winning debut poetry collection from the University of Iowa Press, language doesn’t necessarily come in the form of speech. In the collection’s first poem, “Stutter,” we are introduced to a speaker who has lost the inherent spontaneity of speech: “since I can’t say everlasting / I say every / lost thing.” At once captivating and mysterious, the opening poem doesn’t explain, but creates more questions. What is it that we understand language to be? And how does the possession or dispossession of language change us? To go one step further, how do we catalogue our losses without first naming what we’ve lost?

In the quiet, meditative world of this collection, we are observers. Not unlike the speaker of Giannelli’s poems, whose interactions with the natural world are limited primarily to naming—and thereby attaching meaning to—the things of this world. This world in which “clouds thin to their bones” and “each leaf / pried from shadow / glittering / like aspirins” lives amongst stars that “fall across the earth.” The natural world becomes, in these poems, glorious in its unwillingness to communicate the way humans do. It is the poet, in the end, who speaks.

Giannelli weaves language into a latticework in these poems, raising questions about what words mean to the speaker of these poems and what it means to be able to speak and experience language. In “The Shards Still Trembling,” the speaker dreams of making a lover “shudder / with the simplest words.” In “What We Know,” the speaker strives to communicate through touch: “Touch me on the shoulder / it means memory / touch me on the elbow / it means come follow.” The opening poem of this volume introduces the figure of a speech therapist, through whom we learn of the speaker’s particular and personal awareness of the way in which words are physically and figuratively formed: “How the mouth makes a moon / when we say moon.” We are always, in these poems, conscious of the struggle to contain language and make it obey the mouth, the tongue, the ear, the body. In the same way, we are also conscious of the struggle to control the “things” our words attempt to contain and mean. In “Light-footed,” the speaker concedes, “what does it matter” what we “call” a thing if we don’t have any control over it?

For Giannelli’s speaker, there is no easy way to make meaning for someone who, despite his longing, cannot control or possess his language. There is also the problem of being heard: “When I hit / the carpet, / do not walk over me. Please hear.” In “Gravity,” the climactic poem of Tremulous Hinge, we hear in the word please a plea to be heard on a human, guttural level.

The poems in this collection attend the gap between language and communication in the human world. Ultimately, the speaker revels in this space—not as void, but possibility. There isn’t one way to understand the world, or one word that means one thing to everyone: “The opposite of here isn’t there / there there child there there.”

Chelsea Dingman is a Visiting Instructor at the University of South Florida. Her first book, Thaw, was chosen by Allison Joseph to win the National Poetry Series (University of Georgia Press, 2017). In 2016-17, she also won The Southeast Review’s Gearhart Poetry Prize, The Sycamore Review’s Wabash Prize, and Water-stone Review’s Jane Kenyon Poetry Prize. For more of her work, please visit her website: www.chelseadingman.com