Tom Burckhardt: Creative Seeing

John Yau

Tom Burckhardt’s abstract paintings form one distinct body of work within his diverse oeuvre. He has done installations and made a series of works painted on vintage book covers. I have seen travel journals full of portraits of people he encountered while bicycling in Indonesia. He has made ink-on-paper views of a variety of landscapes and seascapes that incorporated digital images. Burckhardt has looked at a lot of stuff but has never been hierarchical about it. He works across mediums, without trying to fit them all together. But despite all the differences, in each of them he is meditating on the nature of art.

For years Burckhardt has painted on uneven cast-plastic surfaces, adding black dots to the sides to mimic the tacks used to hold a stretched canvas to its wooden support. In his 2015 exhibition at Tibor de Nagy, he showed two groups of paintings, one on cast plastic supports, and larger works done on stretched canvas.

“The casting of the support posits them as sculptures and paintings at the same time,” Burckhardt said in an interview we did in 2011:

because it’s the form of a painting, a canvas, but it’s made in a process related to sculpture. It’s mass-produced and it’s handmade and touched, and then it’s abstract and figurative. It’s all those things coming together under the umbrella of a hybrid of some sort. I don’t like purity. I like the hybridization of things.

By pairing the two kinds of painting under the 2015 show’s title, AKA Incognito, suggesting that something is in disguise, Burckhardt introduces an element of doubt and humor into our experience of his work: are the paintings on plastic pretending to be real? Does this mean the ones on canvas are real? Or are they both real and fake? In an age of rip-offs, copies and fictional memoirs, what do real and fake even mean?

There is something delightful and disturbing about looking at something that you cannot name, that in fact resists any attempt to corral it in simple, commodifiable language. And there is something even more delightful if a name is on the tip of your tongue, then suddenly seems light years away. At the very least, you might be reminded that even if you can afford to possess something, you cannot fully own it, which I think is worth remembering.

Elsewhere in our 2011 interview, Tom spoke of his longtime interest in a phenomenon the Rorschach inkblot test makes use of, pareidolia, or the way the imagination creates patterns, so that you see something you know (face, bat, or gondola) in abstract images:

The whole idea of pareidolia is that it’s an evolutionary thing that we had to develop to instantly recognize friend or foe, it’s a subcortical kind of image, it’s the primary kind of image processing that we have had as a species, and I want to tap into its hook, as in a pop song hook, and to make use of that. If I were a really good abstract painter, as soon as that face starts appearing, I’d want to turn the canvas and run in the other direction. I’m perversely trying to cultivate the thread that comes out of pareidolia, the creation of images, a facial image out of a random stimulus, basically, because random stimulus is the basis of abstract painting, right?

As his observation about this phenomenon suggests, Burckhardt does not want to be “a really good abstract painter,” which is to say that he resists the institutionalized model regarding what constitutes an accomplished abstract painting. This resistance is what threads many of Burckhardt’s distinct bodies of work and styles together. He wants to subvert the standards of judgment integral to our understanding of abstract painting, while being committed to the act of making: he wants to inhabit his doubt and certainty without seeking a one-size-fits-all solution. He is interested in—to use his own words—perversely cultivating the tenuous relationship between creative seeing and the randomness of nature without becoming explicit. He is also interested in following the ramifications of an idea (or something seen in his mind’s eye) to its fullest fruition, no matter how absurd the journey. By courting legibility while resisting it, Burckhardt asks, how and what do we see? And why? What is it that we want from abstract painting?

Burckhardt’s mastery is understated, but it should be evident to anyone who slows down long enough to begin looking at the work. These paintings invite prolonged scrutiny, in which part of the pleasure is seeing how the artist has fitted disparate things together. They are as intricate as the interlocking, overlapping gears of a pocket watch, and as magical.

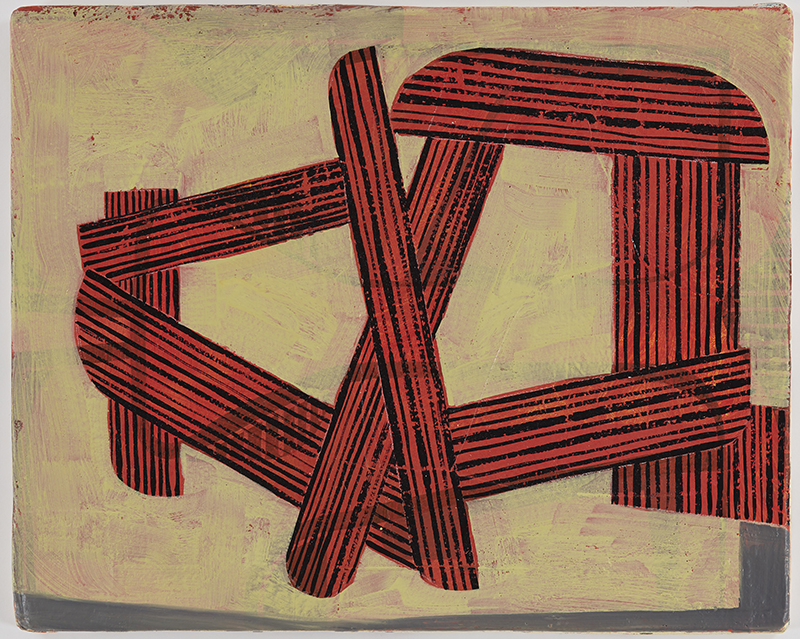

Tom Burckhardt, Extension Rig, 2015, oil paint on cast plastic, 16 x 20 inches, with permission of the artist, ©Tom Burckhardt.

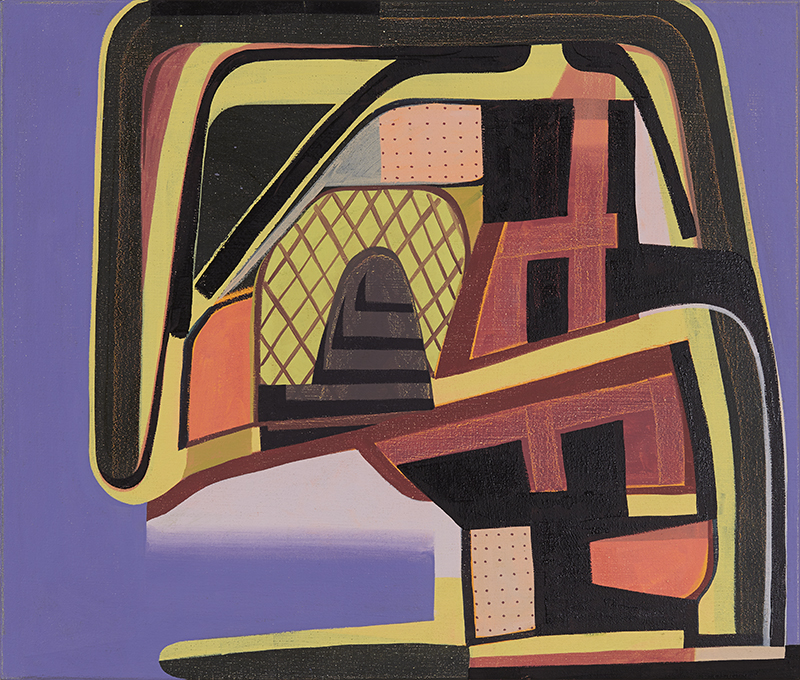

Tom Burckhardt, Dawk, 2015, oil paint on linen, 48 x 60 inches, with permission of the artist, ©Tom Burckhardt.

Tom Burckhardt, Odalik, 2015, oil paint on linen, 48 x 60 inches, with permission of the artist, ©Tom Burckhardt.

Tom Burckhardt, In F Able, 2016, oil paint on linen, 34 x 40 inches, with permission of the artist, ©Tom Burckhardt.

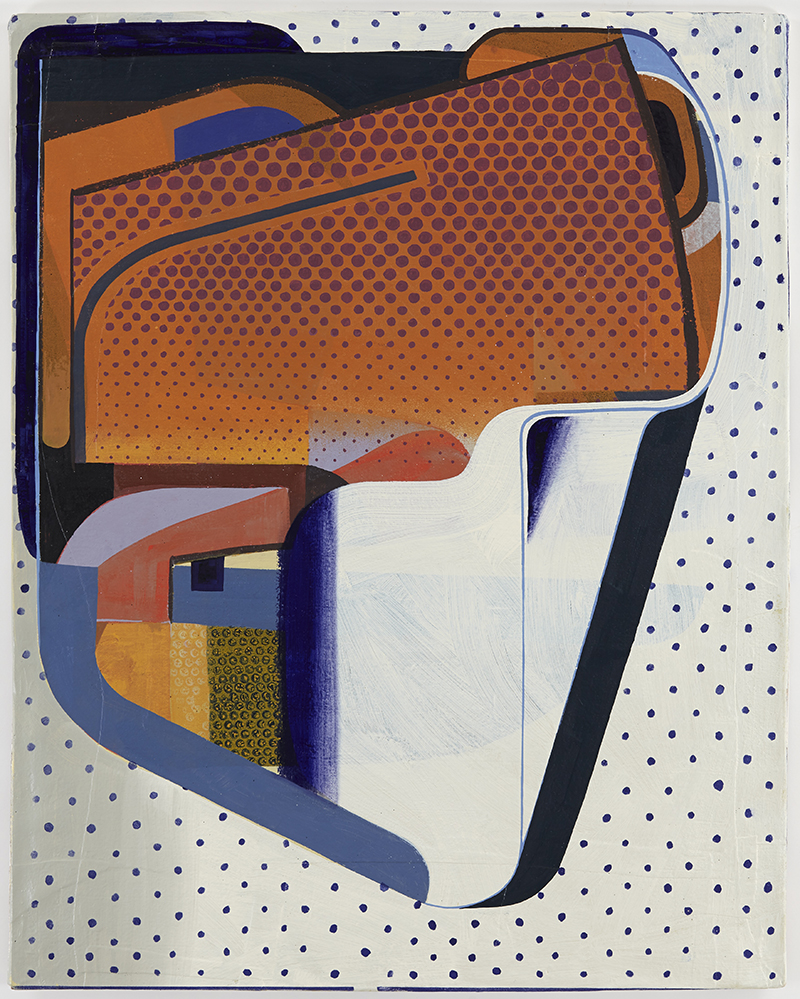

Tom Burckhardt, Avid Antics, 2015, oil paint on cast plastic, 40 x 32 inches, with permission of the artist, ©Tom Burckhardt.

Tom Burckhardt, Extension Chord, 2015, oil paint on linen, 60 x 48 inches, with permission of the artist, ©Tom Burckhardt.

Tom Burckhardt, Prussian Front, 2015, oil paint on cast plastic, 32 x 40 inches, with permission of the artist, ©Tom Burckhardt.

Tom Burckhardt, City Slang, 2015, oil paint on linen, 48 x 60 inches, with permission of the artist, ©Tom Burckhardt.

Tom Burckhardt, Gunung, 2015, oil paint on linen, 60 x 96 inches, with permission of the artist, ©Tom Burckhardt.

Tom Burckhardt (American, born 1964, lives New York, NY) earned a BFA from the State University of New York at Purchase (1986), and studied at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture (1986). A recipient of grants from the Joan Mitchell, Pollock-Krasner, and Guggenheim foundations, he has had recent solo exhibitions at Columbus College of Art and Design Gallery, Columbus, OH; McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX; Weatherspoon Museum, Greensboro, NC; Tibor De Nagy Gallery, New York, NY; Knoxville Art Museum, Knoxville, TN; Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, NY; and Gregory Lind Gallery, San Francisco, CA. An exhibition of his new work will open at Pierogi Gallery, New York, NY, in September 2017.