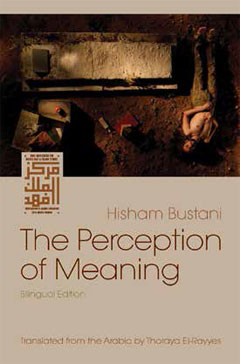

The Perception of Meaning

Hisham Bustani, trans. Thoraya El-Rayyes

Syracuse University Press, 2015

Reviewed by Matthew Nye

In The Great Derangement, Amitav Ghosh characterizes one effect of climate change as having rendered the once improbable into concrete urgent reality. In addition to the obvious environmental challenge, this global shift poses a distinct literary question: how does imaginative writing make credible what is at once materially present and normatively unbelievable? For Ghosh, the dominant modes of literary realism seem ill-equipped to meet the real-unreal anthropocentric present. Part of Ghosh’s critique is formal—the paradoxical demands for and limits on fiction’s ability to capture this new unreal-reality. Part of Ghosh’s critique is willful—given climate change’s relative absence from literary fiction, has contemporary literature abdicated its responsibility to imagine our present reality?

The Perception of Meaning, Hisham Bustani’s third book of fiction and winner of the University of Arkansas’s 2014 King Fahd Center for Middle East Studies Translation of Arabic Literature Award, is a veritable exegesis of the “real.” Bustani embraces our complicated, multifarious present, deftly winding and unwinding absurdities into comic ironies and political obfuscations into material, real-world tragedies. Beyond environmental catastrophe, the collection’s 78 flash fictions depict a highly mediated world. Myth and fairytale abut film and YouTube video; poetry and politics juxtapose waning media celebrity. What is never far from the collection’s self-reflective surface, however, are the gritty material grounds of this new reality, the stakes behind our media images and rhetorical distortions, and the non-fictional touchstones undergirding fiction’s imaginative possibilities.

As his title suggests, Bustani’s ontological focus rests on the oscillation between truth and perception. Bustani holds meaning at a distance. Each sequence title bears partitioning brackets, as if the individual works’ corresponding originals may only be reached through fiction’s mediating barrier. The opening sequence, [Apocalypse Now], cycles doubly inward, whereby Bustani reimagines the Francis Ford Coppola film, itself an appropriative work, and simultaneously calls the reader’s attention to his own act of appropriation. The piece [In Mockery of the Narcissus of the Universe] overlays a satirical retelling of the Narcissus myth with self-reflective mockery. Cultural critique announces itself as critique, appropriation as appropriation. These meta-fictional elements elevate Bustani’s surreal stories into a kind of wakeful dreamscape.

What is unique to The Perception of Meaning is the manner in which the text grounds its self-referentiality. Author and translator endnotes explicate cultural, geographic, and literary references, linking the text’s often surreal imagery with defined real-world antecedents. In this bilingual edition, Thoraya El-Rayyes’s English translation of the Arabic mirrors Bustani’s original work page for page. The Perception of Meaning is a text that seems explicitly written for translation. El-Rayyes’s work adds a further meta-textual layer between meaning and its distant perception. The bilingual reader may occupy the liminal, accretive space between languages, while the English-only reader is continually met by Bustani’s Arabic on the opposite page, the original story beside El-Rayyes’s translation partitioned by its metaphorical bracket.

It is from this self-reflective vantage point that Bustani trains his attention toward themes of cultural alienation, political violence, and environmental degradation. Bustani anchors his surreal imaginings and prose poetics in grounded worldly events. In [Requiem for the Aral Sea], he poses pointed environmental commentary through compressed, surreal vignettes:

When Man placed his hand in the Aral Sea,

it transformed instantly into a desert,

became a graveyard for rusted ships, a playground for the

sands.

Who doesn’t believe in miracles? (129)

In [A Game of the Senses], he offers a parallel vision:

The gas truck plays its tune to attract customers, and to mask

the sound of the dying earth stuffed in canisters. (161)

In Bustani’s fiction, the literary surreal, whether manifesting as the sound of the dying earth or as the actualized miracle, meets the worldly surreal: desertification, post-industrial junk heaps, and petroleum economics. The Perception of Meaning slides effortlessly between these two planes to show both the absurdity of reality and the reality of the absurd.

What Amitav Ghosh voices with regard to climate change, and to which Hisham Bustani might add political violence and media saturation, are the ways in which certain contemporary phenomena resist language broadly and probabilistic fiction in particular. For Ghosh, the paradox seems to be that if one approaches the unreal with realism, the work fails to pass the eye test for what is broadly plausible. If one approaches the unreal with the unreal, the work risks reducing the gravity of the event’s real-life happening. In imagining the projective future of literature, Ghosh writes, “It would seem to follow that new, hybrid forms will emerge and the act of reading itself will change once again, as it has many times before.” Hisham Bustani’s deft manipulation of genre is clearly one of these new forms. If we are to understand our unreal present and projective future, we readers should follow him there.

Matthew Nye is the author of the novel Pike and Bloom (&NOW Books, 2016). His work has appeared in Chicago Review, Fiction International, The Iowa Review, Mid-American Review, and other journals. He teaches at Unity College in Maine.