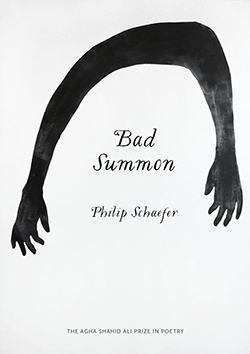

BAD SUMMON

Philip Schaefer

University of Utah Press, 2017

Reviewed by Kristine Sloan

Richard Hugo’s “Degrees of Gray in Philipsburg” serves as the annunciatory spark for emerging poet Philip Schaefer’s debut poetry collection Bad Summon. Hugo’s voice calls to us through the years—“Isn’t this your life?”—and in more than its epigraph the aesthetic life force of Schaefer’s voice channels Hugo’s throughout the collection. His demand for a particular kind of self-reflection finds itself surrounded by the hollowed-out structures and lone curio that signal a town’s economic decay—nothing new for small, rural towns in middle America. In sure enough step, Schaefer continues picking up the pieces of such decay. Yet he also insists upon a kind of romanticism. The mountains, the moon, the kinetics of darkness, Montana—these are the materials by which Schaefer’s speaker comes to grips with his feelings (or perhaps lack thereof) of self-alienation. In a hellish circularity, the speaker finds himself both free and kept, and the distance between these two existential poles yields the psycho-social dilemma that is Bad Summon.

Schaefer tracks a variety of emotional modes through which his speaker views the world . Most important of these is his deeply entrenched skepticism. This is not simple doubt. Rather this skepticism shows an inability to believe in anything, which the speaker announces in “The New World”: “We don’t / believe in anything worth saving.” This skepticism seems to be the root from which other psychic impulses—even a numbness to them—spring forth. Throughout the first section’s landscape, a world full of disparate objects, people, and stories, Schaefer’s speaker is constantly seeking something. But it feels as if no one person, story, thing knows how to belong to another. Belief, that tricky glue, won’t allow for harmonious coherence:

Last week the world started destroying itself again. Images of a

girl without eyes, flat on a trampoline, the air around her more

gasoline than snow. God if god give us snow. A pewter we can

blow dust off of, hold like pencils in the twitch of our fingers and

write new languages for freedom and distance. We await mercy

as if it’s lost luggage.

Even while the speaker notes what might be sources of hurt, badness, evil, or even just decay, it’s as though he is still trying to bear witness to something in his everyday life, to find a sign or symbol around which he can create meaning. At times though, the objects, people, and stories feel only surface-deep. Does this reflect a desire to keep the reader from traversing any further into the speaker’s emotional spheres—to hold us in that same in-between, watching and waiting alongside him? Schafer’s poems resist easy symbols. It can be hard to tell if a symbol has truly arisen or if the speaker is simply eager to turn something or someone into a symbol—the human need to shape self-made relics reflecting the need for belief. In “Evening News,” the speaker lists reported crimes: “A gas station clerk / found with his neck / boiled red in the register. / All for a night of light / heads. The football team / record resting on the arm / of a boy who is addicted / to the way he feels / after midnight.” And in “Sisyphus Self”: “On the news tonight a newlywed / pushed her husband off a cliff in Glacier. / On the news I see myself pushing against / everywhere.” While he admits later, in “Another Language,” “I have an addiction / to stories like this,” this grim compulsion seems like the same force that notes a cairn by an abandoned railroad track, or takes a jar of fireflies and shakes them just to briefly, and quietly, witness “so much death / lighting up. Manhattan / in my hands.”

What the speaker really seems to want to grasp hold of, to make his own, is some primordial entity, something yet to be found and felt, a shock to his system, arguably a cathexis. As if answering the commencing call in “The New World” to return to a time and place “when we were still undiscovered,” he finds himself witnessing his own self-destructive frisson in someone else: “I can’t remember who held the needle / but earlier at the house I watched him take metal to skin / as if pleasure were a hundred endangered doves / plumed in his veins. I saw neon suns explode / over an undiscovered ocean” —uncharted emotional territory for the speaker, which he hopes to find elsewhere: “I open / your mouth with my finger in search / of harmony, undiscovered asteroids.”

In its confrontation with ugly feelings—boredom, indifference, self-estrangement, hatred—Bad Summon harnesses a raw cadre of psychological nodes that speak to the ways in which small worlds roil themselves:

In the middle of Montana, with backs broken by beauty, all we know is cadaver, spleen, amethyst, smoke screen, grenade pins, Christ’s skin crinkling, newspaper ink, children laughing under floorboards, deer stink, night sweats, beverages birthing forgive forgot forever until we meet again. God if god if got if good for nothing.

And what can really be done to yank the veil from it all except to constantly heft the objects of one’s reality, one’s lonesome town, and see what sparks into flame and what doesn’t?

Kristine Sloan received her MFA from the University of Wyoming, and her work can be found in Sporklet, Yes, Poetry, smoking glue gun, The Margins, and elsewhere. A proud Baltimore native, she’s soon to be based in the Midwest.