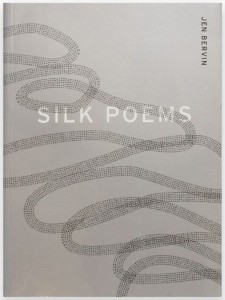

Silk Poems

Jen Bervin

Nightboat Press, 2017

Reviewed by Sarah Thompson

Jen Bervin’s Silk Poems exists within a larger multimodal art and research project, the culmination of which is a poem embedded in silk screen using nanoimprinted gold splatter. The book, itself a beautiful object, with a slick, metallic cover and delicate semi-translucent pages, reproduces the text of the nanoscale poem, framed by paratext. Silk Poems manifests an ethos of continuity and presence as it places temporalities, modalities, discourses, and disciplines in communion. It enacts a sense of history predicated on intimacy: a history less narrative than embodied; quotidian and multiple rather than hegemonic.

Bervin began her interdisciplinary project in response to research from Tufts University’s Bioengineering Department, where scientists developed “reverse-engineered liquified silk” for use in a biosensor. The immune system accepts silk “on surfaces as sensitive as the human brain.” What Bervin calls the “RARECOMPATIBILITY” between silkworms and humans includes our close relationship through millennia of sericulture, as well as the biocompatibility of silk and human tissue; she asserts a continuity from the cultural compatibility to the biological. Thus, Bervin seeks to imagine the traces of this relationship, of silk embedded in the human body, and the lives of the worms themselves as present in the moment, both vulnerable and intimate.

This moment is an instance of inscription, of writing, which is always a meeting of text, textile, and body. There are traces in the Chinese language of the close relationship through the millennia between silkworms and humans, and between silk and language, a subject the speaker in Silk Poems, a silkworm, explores:

LOOKTHERADICALFORSILK

ISINTHEWORD

TRANSLATE

繙

The project is an act of translation on many counts, a putting-in-relation and transfer between embodiments (insect and human), artistic modes (silk nanopoem and book), languages, and cultures. The fact that a silkworm, our intermediary, guides us through these interstices helps create the sense of intimate continuity. The choice of speaker privileges the small, the invisible, the vulnerable. The anthropomorphized silkworm speaker, though, is funny and heroic, and also strange. She says of herself:

AGLEAMINGBLACK

FACETHE MOON

WOULDLICKIFITCOULD

ILOOKGOOD

Centering the silkworm herself brings to the fore that which is most easily erased in the long history of silk textiles and highlights the place of the body, whether insect or human, in this history. While the speaker gestures often to historical anecdotes related to silk, the narrative thread in the poem is not linear but cyclical: that of the life and reproductive cycle of the silkworm. The speaker describes the process of transformation over this life cycle in details sometimes lovely, sometimes abject, always sensual:

IMSOHUNGRYI

SHUCKMYSKIN

ANDDEVOUR

ITWHOLE

and

INSIDEME

SPIRACLES

CONCENTRIC BRANCHES

AWEFT

The poem’s structure, which recalls both silk filaments and strands of DNA, gestures graphically to the act of spinning and to the biochemical makeup of silk—another kind of translation, one code emulating another. Bervin’s thread-lines travel (“trans-“) through the body of the reader in a way that embeds the utterance between two ends, a gravity exerted from either side. At times, a lag between the sonic register and the semantic creates a spatial and temporal opening where “a brin unfurls from the frisson tangle.” Future and past are woven in the instance of the utterance. The silkworm’s description of her own and her mother’s reproductive cycle extends the implications of this temporality wherein the past and future are embedded and emergent in the processes of biological development and history:

FOUR

WINGS

OFTHEFUTURE

FOLDED

ACROSS

HERCHEST

Intertextuality and intertemporality are part and parcel of a reconstruction of history that presents the continuity of materiality via reproduction. Our worm guide quotes contemporary poetry and the I Ching, draws from etymology and biology, moving back and forth between epochs and cultures in a way that parallels the “ELLIPTICAL/MOTIONS” of the silkworm’s head as she writes “SIDETOSIDE/INFINITYLOOPS.”

Bervin embeds in the book a trace of the transfer from nanoscale silk object to reproducible book object. An image of the poem-thread loops in the corner of the pages, growing longer on each subsequent one. The thread gestures to the existence of the nanopoem, as well as to its absence, in the same way that the instance of silk written in the body may inscribe a material continuity, but also marks the body’s ultimate vulnerability. While the thread is an image of infinity, infinitude is encountered through and within manifold finitude. The silk-embedded poem itself is too small to read, except under a microscope. It is the product of a practice of tremendous care and tenderness. Silk Poems creates a sense of community built on the “PREPONDERANCEOFTHESMALL,” of tiny gestures, illegible traces, and

OUR

SHORT

PRODUCTIVE

LIVES.