Ruth Hellier-Tinoco

Co-mingling Bodies and Collective Postmemory: Creative Theater and Performance Experiments as Humanities-Engaged Community Building

The humanities . . . are disciplines of memory and imagination, telling us where we have been and helping us envision where we are going.

—Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences1

The humanities comprise those fields of knowledge and learning concerned with human thought, experience, and creativity.

—American Council of Learned Societies2

The humanities can be described as the study of how people process and document the human experience.

— Stanford Humanities Center3

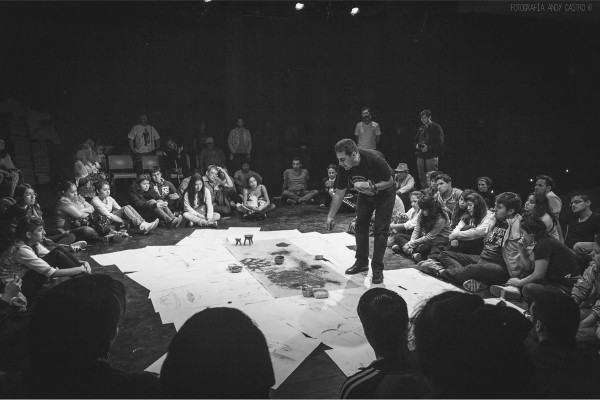

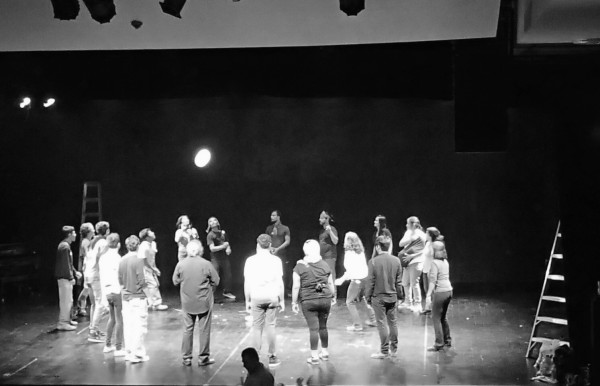

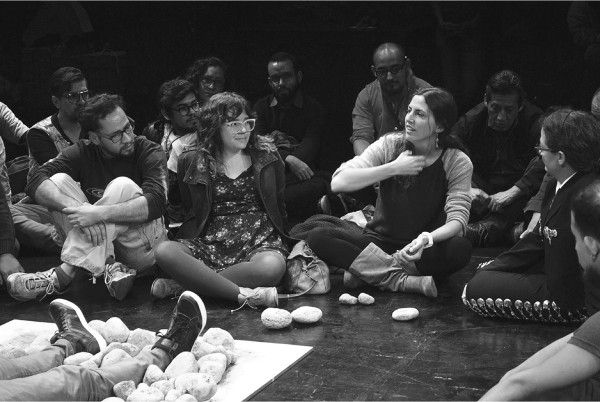

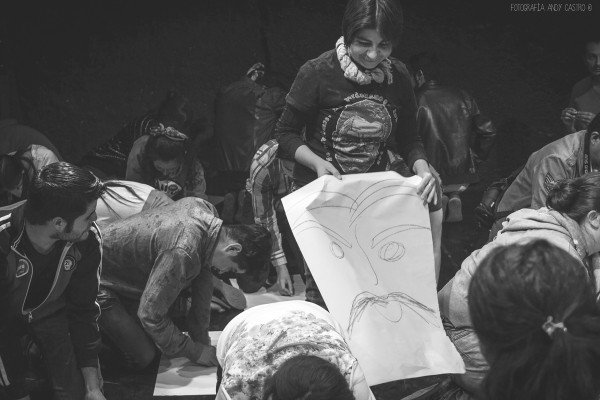

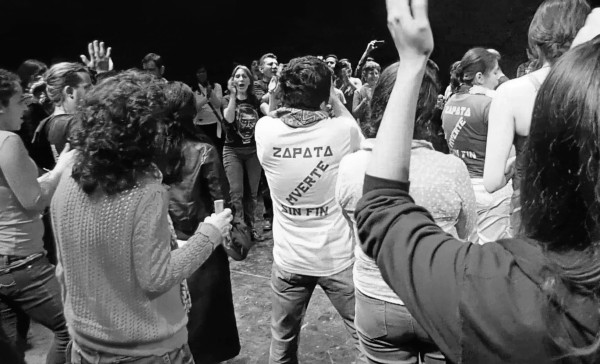

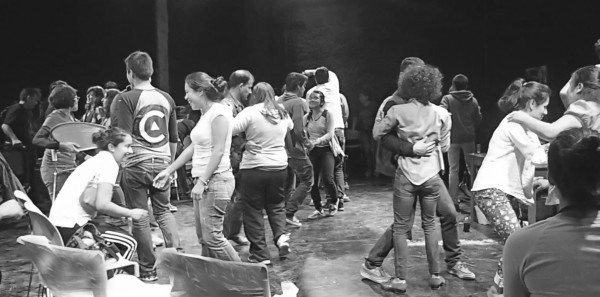

Figs. 1-13. Zapata, Death Without End. La Máquina de Teatro, A la Deriva Teatro, Teatro de la Rendija, Colectivo Escénico Oaxaca, and A-tar. (La Máquina de Teatro, including photos by Andy Castro, J. Martin, ensemble participants, R. Hellier-Tinoco, 2015.)

Trans-temporal Embodied Connections: Performing Palimpsest Bodies

As humans we are deeply aware of our bodies as containers and transmitters of memories and histories through trans-temporalities. We become conscious of alterations and transformations over time; of accumulated layers, sediments and iterations; of multi-temporal connections; of discontinuities, repetitions and juxtapositions; of remains and traces. We experience trans-temporal relationships with our predecessors, our prior selves, our environments and our pasts. We connect with collective memories and bodies of history through myriad remains in diverse forms: literary texts, oral stories and linguistic codes; photographs, images and objects; embodied archival repertoires of movements, gestures, voices and sounds; smells and tastes; architectures and spaces; ephemera and barely tangible existences.

As creators, performers, spectators, participants, teatristas, practitioners and witnesses, we make use of these connections to generate possible futures.4 In performance projects and creative theater workshops, we can create communities through playful and rigorous transdisciplinary experimentation, performing powerful re-visions that provoke and challenge. Through these performance practices, we can “activate and open the past within the present.” 5 We can “imagine other ‘potential historical realities’ and thereby ‘open up a different future.’” 6 Articulating “a relation between the body as a holder of collective memory and as an unfolding of poetic presences,” 7 we use these creative processes to work through productive tensions of trans-temporal traces by performing palimpsest bodies.

In this essay I focus on an experimental performance project in Mexico that offered great potential for generating communities of action through humanities-engaged processes of memory, imagination, creativity, and experience. Conceived and devised by one of Mexico’s most renowned theater companies—La Máquina de Teatro—the project, Zapata, Death Without End explored the interrelated processes of “telling us where we have been and helping us envision where we are going” through deeply embodied and corporeal practices. It encompassed five diverse theater collectives and co-participating spectators performing and receiving complex transdisciplinary and trans-temporal experimental practices on a theater stage in Mexico City.

I emphasize that, by playing with memories and histories as tangled temporalities through embodied knowledge, we can enable explorations of complex pasts within complicated presents to create communities of action and becoming. These communities bring together interdependent people through difference; they generate a sense of place, however transitory and temporary; they offer experiences of shared fellowship through diversity; and they propose opportunities to live differently right now.

My discussion is structured in two principal sections: in the first section I offer descriptions of embodied knowledge, postmemory, rememory and palimpsest bodies; and in the second section I discuss three key strategies of the Zapata project. Finally, I conclude by linking the Zapata project with a ten-week undergraduate course that I designed and teach at the University of California, Santa Barbara. This course enables students to play with memories and histories as tangled temporalities through embodied knowledge, exploring complex pasts within complicated presents to create communities of action and becoming. For these analyses of transdisciplinary devising and performance I combine specific material-gathering processes with extensive long-term experiences as a creative artist, performer, teacher and facilitator of performing arts, music, theater and dance; as a researcher of performance (engaging fields of performance, dance, theater and music studies); and as a scholar of performance and cultural practices in Mexico.8

Transdisciplinary Experimentation: Embodied Knowledge, Postmemory and Rememory

experiment:

a course of action tentatively adopted without being sure

of the eventual outcome [noun]

to try out new concepts or ways of doing things [verb]

If the past is never over, or never completed, “remains” might be understood not solely as object or document material, but also as the immaterial labor of bodies engaged in and with that incomplete past: bodies striking poses, making gestures, voicing calls, reading words, singing songs, or standing witness.

—Rebecca Schneider, Performing Remains9

How does one come to inhabit and envision one’s body as coextensive with one’s environment and one’s past, emphasizing the porous nature of skin rather than its boundedness?

—Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire10

. . . scenic works . . . articulate a relation between the body as a holder of collective memory and as an unfolding of poetic presences.

—Gabriel Yépez11

Embodied Knowledge

Renowned performance studies scholar Diana Taylor has drawn attention to the significance of embodied knowledge, embodied memory and presence. In her seminal study The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas, she particularly advances the importance of recognizing bodies and embodied knowledge as of great value, even though they are frequently devalued or regarded as hierarchically less important than writing.12 She notes that “writing has paradoxically come to stand in for and against embodiment.” 13 Within her discussions of cultural memory, archives and repertoires, Taylor considers the valorization and perpetuation of certain kinds of materials: “The dominance of language and writing has come to stand for meaning itself. Live, embodied practices not based in linguistic or literary codes, we must assume, have no claims on meaning . . . . Part of what performance and performance studies allows us to do, then, is take seriously the repertoire of embodied practices as an important system of knowing and transmitting knowledge.” 14 As Taylor describes, “Embodied expression has participated and will probably continue to participate in the transmission of social knowledge, memory and identity pre- and postwriting.” 15 Crucially, she goes on to note that: “If performance did not transmit knowledge, only the literate and powerful could claim social memory and identity.” 16

Postmemory and Rememory

To address ideas of embodied knowledge for creating community through experimental performance contexts, I particularly connect with concepts of postmemory and rememory. Both incorporate trans-temporal relationships through an understanding of bodies as transmitters and holders of memories and histories. Bodies connect traces of collective and personal memories, as “the past” is experienced in the present through remains, fragments, and ephemera.

For aspects of postmemory, I draw on the work of Marianne Hirsch, who describes an overt relationship between a present generation and past actions where the relation with the past is active and generative, mediated by imaginative investment, projection, and creation.17 For transdisciplinary experimental performance projects, postmemory encompasses key elements:

—understanding “the past” as experiences transmitted through stories, images and behaviors using remains of oral texts, written documents, visual images, objects and embodied archival repertoires;

—creating through “the past” experienced in the present as traumatic fragments of events that are translated into an equally fragmented dramaturgical structure;

—using fragments of stories, images and behaviors not to generate narrative reconstructions, but as re-imaginings and new creations;

—playing with cultural fictions and historical realities and combining fragments of remains in unexpected ways to generate contradictions, ambiguity, complexity and in-betweenness;

—opening up questions of truth, history and memory to generate re-visions for possible futures.

For the concept of rememory I engage the profoundly important work of Toni Morrison.18 For Morrison, rememory indicates embodied experiences of individual and collective stories and is a continued presence of something forgotten that returns through a body in the form of visceral experiences. Rememory embodies an experiential doubleness of “my memory” and “not my memory” through presences remaining as traces that are concealed and suddenly revealed. Rememory comprises an overt temporal relationship between past histories/memories and present experiences. For transdisciplinary experimental performance projects, rememory incorporates key elements:

—valuing experiential and embodied performance practices as forms of inquiry to probe collective and personal histories and memories;

—using practices and aesthetics of deeply sensorial participation;

—understanding bodies as archives and as containers and transmitters of memories;

—engaging a sense of doubleness (my memory and not my memory) connecting individual and collective memories and individual and collective histories through processes of body-to-body transmission.

Palimpsest Bodies

Bringing together embodied knowledge, postmemory and rememory in experimental performance projects, I propose the interpretive-creative concept of palimpsest bodies. A palimpsest contains layers, traces, and ephemera. It blurs boundaries and creates productive temporal connections. Each body in performance is plural, performing relationships that are trans-temporal. Within theater labs and performances, these remains are performed through strategies of coexistence, simultaneity, plurality, multiplicity, sedimentation, interweaving and layering, re-using fragments to create accumulated iterations. Encompassing movements over and through the same space and place, and playing with notions of visibility, ephemerality, ghosts and specters, there is always a sense of stories that are caught in the middle.19 As investigative experiments of collective creation, performing palimpsests involves performing uncertainties, ambiguities and contradictions; valuing plurality, multiplicity, liminality and in-betweenness; and questioning clear-cut notions of truth/fiction and reality/history. Palimpsest bodies of postmemory and rememory combine present bodies and past bodies of history, as traces and remains of bodies are re-imagined and performed through present bodies, as processes to generate possible futures.20

Zapata, Death Without End: A Model for Creating Community

A Fragment

Venue: the studio theater, El Chopo University Museum, Mexico City.

Date: March 2015.

Five groups of performers from five diverse theater collectives from five different regions of Mexico stand in a circle on a theater stage.21 The auditorium is empty. The space is full of fixed rows of velvet seats facing forward to a proscenium-arch stage. Small flights of steps on either side of the stage connect the auditorium with the stage. The public enters the studio theater. As the spectators walk through the auditorium and move to sit in the seats, performers approach them, inviting and encouraging them to walk up the five steps and onto the stage, as bright stage lights shine down on the gathering assembly.

On stage, people walk around and chatter. Before long, the stage contains about one hundred people, as spectators and performers mingle and merge. It is not clear who is who. Some wear what seem to be obvious costumes—one woman wears a charro (mariachi) suit of a black jacket and pants with silver buttons down the sides; one wears a large hat and has a moustache stuck on her face. Some are clothed in t-shirts emblazoned with the iconic face of Emiliano Zapata and the words “Oaxaca Colectivo.” Five people wear matching crisp white shirts and neat ties. All seem to be in a liminal and palimpsest state of subjunctivity, waiting and ready for possibilities. There are no clear demarcations and delineations of space indicating which bodies should go where. Boundaries between active performers and passive spectators are blurred and crossed as audience members are invited to become co-participants. They become palimpsest bodies in performance. For three hours, everybody is on stage together, moving around and being moved around.

This fragment of performance is part of the culmination of a year-long project titled Zapata, Muerte Sin Fin — Zapata, Death Without End.22 Throughout the project, five disparate groups of individuals collaborated through intensive workshop sessions, through sharing at-distance with virtual technologies and through live performance. This multi-ensemble project was part of the diverse body of work created and facilitated by one of Mexico’s leading contemporary, body-based, experimental theater arts companies: La Máquina de Teatro ~ the Theater Machine. Founded and directed by Juliana Faesler and Clarissa Malheiros, this company has consistently worked at the cutting edge of contemporary theater and scenic arts for over twenty years, creating and facilitating a wide array of performances, laboratories, and projects, all of which specifically seek to create and develop senses of community.23 The Zapata project offers the potential to generate communities of action through humanities-engaged processes of memory, imagination, creativity and experience through multiple strategies. Here I briefly outline three of these:

1. At heart, the project engages body-based collective theater processes for sharing lives through palimpsest bodies in performance. This project incorporated an open- and multi-layered structure, which specifically worked through and with bodies, embodied knowledge, expression, and memory. For collective postmemory, the project used the core provocation of revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata—one of Mexico’s most iconic figures—engaging questions: What is the value of land? What is liberty? What is a hero? The project brought a community into being through the involvement of five very different theater groups. They travelled great distances to be present with each other for intensive workshop sessions and live performance. They worked through experimental devising strategies to generate embodied responses. The five ensembles comprised diverse groups of people who worked with supportive interdependence in their workshops and performances. And, in the final performances, the public spectators who attended and co-participated were incorporated into the processes to generate another transitory community.

2. The five collectives also shared at-distance through virtual technologies. Within discussions of how humanities can contribute to the creation and development of communities, one specific provocation seeks to explore notions of communities in relation to shared physical and social space, asking: “Is the ‘network’ the latest form of community, now disconnected from the preconditions of shared physical or social space?” 24 The Zapata project certainly involved a network: five locationally disparate groups (some many thousands of miles apart) were seeking to work through collaborative engagement via virtual technologies. However, in this case, the shared physical spaces—workshop rooms and the theater stage—were crucial elements. Live bodies interacted through smell, taste, touch, and deeply sensorial experiences. This project offered the inclusion of diverse aesthetic practices, which performed resistance to homogeneity and conformity through a model of radical plurality and difference. All worked through collective postmemory of Zapata (a form of social memory), but the cultural expressions and responses encompassed multiple embodied forms.

3. This project involved co-mingling and co-participation of performers and spectators for three hours on a theater stage—performing palimpsest bodies through embodied knowledge and collective postmemory and rememory. With a fluid yet structured framework of collective participation—comprising fully rehearsed scenarios, improvisational scenarios, and deliberately inclusive scenarios of “doing” with the spectators—the performances engaged a politics of invitation by sharing fragments of lives. The event itself created a dynamic, liminal community; a complex and chaotic ever-evolving participatory and sensory experience of serious playfulness through imaginative and generate postmemory re-imaginings. The creative stage space became a place of community: transitory but deeply experiential. The space was constantly constructed, deconstructed and reconstructed, creating palimpsests of making and unmaking. It became a palimpsest of performative co-existence, inclusion, integration, cooperation, communitas, and convivio.

Radical Movements

In his work on radical movements, race and state violence, renowned scholar and activist George Lipsitz has described how communities can be called into being through performance, particularly connecting past and present.25 He portrays expressive cultural works as “archives of collective struggle, as repositories of collective memory.” 26 Conspicuously, he also draws attention to a problematic tradition within the arts that “has taught people to derive aesthetic pleasure and an elevated sense of self-worth from feelings of empathy, sympathy, and pity that the depictions of painful social realities evoke. Rather than serving as provocations for action, these can produce political passivity and quiescence.” 27 Lipsitz goes on to explain how “[t]he aesthetic realm becomes an arena in which people learn to feel rather than act, and where social conditions serve as mere prompts for affect.” 28 In terms of historical narratives, Lipsitz explains how historians frequently craft narratives that appeal to “‘feeling good about feeling bad,’ . . . imagining that they are winning allies by engaging them in stories about struggle, sacrifice, and suffering.” 29 He then offers a framework to “avoid the trap of feeling good about feeling bad” which involves renegotiating “the terms of cultural reception. Radical movements do not just promise future social change, they offer activists an opportunity to live differently right now. They are crucibles of new ways of knowing and new ways of being . . . radical movements deploy expressive culture as a way of creating the seeds of a new society inside the shell of the old.” 30

What is so fundamental and fascinating about the Zapata performance project of La Máquina de Teatro is the context that specifically offers participants (both performers in the five ensembles and spectators attending the live events) the opportunity to be activists within the frame of the events. From the workshops in which five diverse ensembles generate performance ideas to the live co-participatory performances on stage, these environments are crucibles of new ways of knowing and new ways of being. The project specifically calls communities into being, by connecting past and present through embodied knowledge, creating seeds of new possibilities inside the shell of the old through palimpsest bodies.

For the duration of the performance, the space is a container of diversity, with no objective of generating unity or sameness. The structure involves performers and public co-mingling and co-participating on a theater stage in Mexico City, creating community through postmemory. The co-participating audience not only view, witness and experience performances by the five ensembles of performers, they also write on stones, listen to stories, throw darts, draw faces, drink mezcal, eat mangoes, smell gasoline, dance together and finally eat shrimp stew together, before walking back down the steps off the stage, through the auditorium and into the cold night air.

This is a model of community engagement of difference in the “now” of the moment, but within a multi-temporal framework, generating an interweaving, intertwining and unfolding socio-political aesthetic. Literally every body is incorporated into performing palimpsest bodies, aware of traces and connections across time and space. Every body is involved in multiple journeys, subjectivities, rememories and re-visions, interrelated through the collective postmemory of Zapata. The dynamic space of the workshops and theater is one of fellowship and sharing, however transitory. I suggest that generating live creative collective environments for re-imagining through shared memory is particularly crucial. Such practices and processes facilitate co-mingling and co-participation through and across bodily difference. There is no attempt to create a unifying aesthetic, technique or practice, and linear narratives of sameness are always avoided. Rather, collective postmemory as palimpsest bodies teases out layers, traces, moments and ephemera—a form of humanness that is appropriate for creating communities in and through humanities as processes of creating expressive cultural works.

Here I engage the deeply evocative words of Brazilian performance studies artist and scholar Eleonora Fabião for another explanation of using pasts to connect with presents to create futures through embodied experiments. Through this poetic and insightful exposition, she describes the complexities of multi- and a-temporal coexistence in relation to imagination, sensorial perception and bodies:

In a corporeal sense, the so-called past is neither gone nor actual, it is neither exactly accumulative nor does it simply vanish—the body intertwines imagination, memory, sensorial perception, and actuality in very sophisticated ways. The body itself moves according to these intertwinements while permanently producing new mnemonic, sensorial, actual, and imaginative connections that generate movement. In a corporeal sense, the past is a becoming.31

These embodied expressions, involving co-mingling, multi-aesthetic and open performance frameworks, allow people to play with iterations, presence, accumulations and evidence. These performative processes can enable the challenge of prejudice and insularity; the questioning of established hierarchies and stereotypes; and the possibility of multiple and fluid relations through performing palimpsest bodies.

Humanities and Experiential Embodied Higher Education

Over the course of twenty years, the artists of La Máquina de Teatro have developed a wide range of theatrical and performative projects with embodied knowledge and experimentation at the core. Each project facilitates the generation of communities of action through humanities-engaged processes using memory, imagination, creativity, and experience. Interpreting these complex corporeal practices through the frame of palimpsest bodies offers insights into their experiments with trans-temporal relationships, through an understanding of bodies as transmitters and holders of memories and histories, playing with remains, fragments, and ephemera. In particular, the Zapata project provided an exceptionally potent environment for community building through performing palimpsest bodies. Using overtly shared “remains,” through postmemory of collective histories and rememory of common and individual embodied experiences, this year-long project and final co-participatory performance event embraced an ethics of inclusion and risk-taking. By facilitating the inclusion of multiple theater collectives and the attending public, the creative community encompassed a vibrant multiplicity of experiences and aesthetics, while discouraging aesthetic conformity and embracing difference. The shared remains were performed through strategies of coexistence, simultaneity, plurality, multiplicity, sedimentation, interweaving and layering, reusing fragments to create accumulated iterations comprised of individual stories, experiences, journeys, and selves.

I suggest that this form of humanities-based creative community embedded in fundamentals of embodied memory and creative imagination should be a core element within teaching and learning contexts of higher education. Here I draw again on the work of Lipsitz, who describes how “the universities in which we work are important sites in society. The ideas learned and legitimated inside the institutions of higher education determine how society functions.” 32 The Zapata project encompassed numerous ideas that I suggest should be legitimated inside institutions of higher education that offer positive strategies and models for societal functioning. These include: embodied knowledge as creative practice and process; body-to-body transmission of memories and histories; equal inclusion and validation of diverse bodies, narratives, stories and “remains”; risk-taking and experimentation without known outcomes; accepting uncertainties, ambiguities and contradictions; valuing plurality, multiplicity, liminality and in-betweenness; and questioning clear-cut notions of truth/fiction and reality/history.

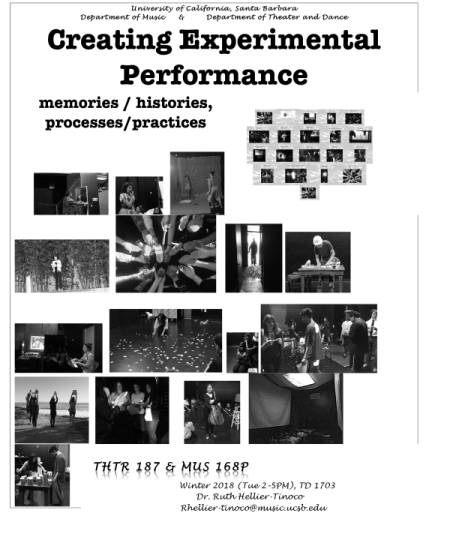

In my own performative-creative work over the last thirty years, as a professional performer-facilitator and as a professor in higher education in the United Kingdom, I have incorporated these ideas in multiple forms. Over the last seven years within higher education in the U.S., I have also designed and introduced an undergraduate class that specifically engages the ideas and strategies discussed in this article. The course—titled “Creating Experimental Performance: memories-histories, processes-practices”—takes place within a small theater studio at the University of California, Santa Barbara. I designed the course to enable a diverse enrollment of students to engage in an ethics of inclusion through embodied knowledge and with creative risk-taking. Each week, for two hours and thirty minutes, I facilitate the students in collective and individual processes of creative practice. As they move, gesture, speak, laugh, and interact, they create sensory experiences from personal and collective memories. They work with deeply personal family photos; with temporally distant images and newspaper texts of the “dirty 30s” dust bowl; with an individual object that holds resonances; and with shared musical experiences. On the grassy courtyard outside the studio, the students place individual stones in secret hiding places as personal markers of memory, returning to them at later times to experience transformations. With each process each body in the workshop performance is plural, performing relationships that are trans-temporal. The students play with memories and histories as tangled temporalities through embodied knowledge, exploring complex pasts within complicated presents to create communities of action and becoming.

This is a course based specifically in experiential embodied collaboration and shared learning, as indicated in the syllabus:

As this is an experimental workshop-based course, you will work collectively with classmates, developing ideas and performance work. This requires trust and sensitivity to each other. The class should be a safe space in which you can all explore new ideas.33

For two hours and fifty minutes each week over the course of ten weeks, the space and event are transformed into an environment of intense community and diversity. Through “Creating Experimental Performance,” students create a transitory and interconnected visceral community, generating deeply embodied responses of re-imaginings. Together, the undergraduate students are diverse but interdependent. They create, discuss, and move through a fluid yet structured framework of collective embodied participation, drawing on fragments of remains as memory and history, both personal and collective. Through ideas of palimpsest bodies of postmemory, of experiences of rememory, and of performance as discontinuities, co-mingling and co-participatory, the students create unexpected encounters that stimulate and surprise. They create unfinished performances of work-in-progress, not for an unknown audience, but for the community of themselves and for me as their facilitator and instructor. We are the community, transitory but humane. Through these unfoldings, the students express their sense of fellowship for and with each other. They learn to emphasize and value embodied and experiential knowledge and learning, respecting deep diversity without a need for uniformity and facilitating creativity by connecting bodies as holders of collective (and personal) memories and as unfoldings of poetic presences.

Fig. 14. Cover of Syllabus for Creating Experimental Performance: memories/histories, processes/practices, taught by Ruth Hellier-Tinoco, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2018. (Ruth Hellier-Tinoco, 2018.)

The creative projects of La Máquina de Teatro enable deeply experiential environments for exploring human experiences; these same strategies offer great potential within higher education. I suggest that these poetic, aesthetic, sensorial, and imaginative co-mingling performing and creating bodies are fundamental to the generation of transitory, diverse, and interdependent communities. They are crucibles of new ways of knowing and new ways of being, telling us where we have been and helping us envision where we are going, through deeply embodied experimental practices of memory and imagination. By playing with memories and histories as tangled temporalities through embodied knowledge, we can enable explorations of complex pasts within complicated presents to create communities of action and becoming, with opportunities to live differently right now.

Fig 15. Undergraduate students participating in Creating Experimental Performance: memories/histories, processes/practices, taught by Ruth Hellier-Tinoco, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2017. (Ruth Hellier-Tinoco, 2017.)

NOTES

1 Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences, The Heart of the Matter.

2 National Humanities Alliance, “About the Humanities.”

3 Stanford Humanities Center, “What are the Humanities?”

4 In Mexico, borders between creative artists and scholars are fluid. The term “teatristas” refers to those involved with performance, theater, dance, and scenic arts, drawing in scholars, active makers, and audiences.

5 Heathfield, “Then Again,” 30.

6 Heathfield, ibid. Heathfield was reiterating ideas of Jan Verwoert in “The Crisis of Time in Times of Crisis.”

7 Yépez, “Encuentro International,” 93.

8 Specific methods included: presence at and participation in live workshops and performances; interviews with artists and company members; analysis of documentation produced by La Máquina de Teatro; analysis of published performance reviews; and creation and performance of my own live theater performance, using a practice-as-research-in-performance (PARIP) methodology.

9 Schneider, Performing Remains, 33.

10 Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire, 82.

11 Yépez, “Encuentro International,” 93. All translations from Spanish are my own, unless otherwise stated.

12 I suggest that this is particularly the case within academic contexts of higher education.

13 Taylor, ibid., 16.

14 Taylor, ibid., 25–26.

15 Taylor, ibid., 16.

16 Taylor, ibid., xvii.

17 “‘Postmemory’ describes the relationship that the ‘generation after’ bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before—to experiences they ‘remember’ only by means of the stories, images, and behaviors among which they grew up. But these experiences were transmitted to them so deeply and affectively as to seem to constitute memories in their own right. Postmemory’s connection to the past is thus actually mediated not by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation. To grow up with overwhelming inherited memories, to be dominated by narratives that preceded one’s birth or one’s consciousness, is to risk having one’s own life stories displaced, even evacuated, by our ancestors. It is to be shaped, however indirectly, by traumatic fragments of events that still defy narrative reconstruction and exceed comprehension. These events happened in the past, but their effects continue into the present,” Hirsch, Postmemory. See also, Family Frames, The Generation of Postmemory, and “The Generation of Postmemory.” Hirsch developed her concept of postmemory in relation to the Holocaust.

18 Morrison, Beloved.

19 As Carolyn Steedman describes in Dust: The Archive and Cultural History, “You find nothing in the Archive but stories caught half way through: the middle of things; discontinuities,” 45.

20 These relationships are evident through the performance and reactivation of remains of bodies of history, which exist in multiple forms and modes (including, but not limited to, visual images, written historical accounts, spoken phrases, sculptures, objects, architectural forms, locations, embodied archival repertoires of dances, songs, gestures and poses, foods, smells, tastes, and many forms of specks, glimmers, and ephemera).

21 Jalisco, Oaxaca, Tamaulipas, Yucatán, and Mexico City.

22 Zapata, Muerte Sin Fin, March 2014 to March 2015. Residency el Foro del Dinosaurio del Museo Universitario del Chopo, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City. Concept and direction: Juliana Faesler. Production: Moisés Enríquez and Sandra Garibaldi. The five collectives were:

1. La Máquina (Mexico City), directed by Faesler and Malheiros. For this project, Faesler and three other participants formed the ensemble. Two were particularly experienced in experimental devising and one more familiar with dance and the folklórico repertoire. Participants: Juliana Faesler (director), Sandra Garibaldi, Carmen Ramos, Isacc López.

2. A la Deriva Teatro (Guadalajara, Jalisco), a professional community and schools theater company, creating theater work to enable students and children to think about their current lives. For this project, this company used a flexible framework of participation, engaging a few young professional actors to take part in the workshops and performances. Participants: Susana Romo and Fausto Ramírez (directors [Ramírez is a renowned director with a long career with University of Guadalajara]), Horacio Quezada, Alejandro Rodríguez, Viridiana Gómez Piña and Ana. Susana and Fausto’s 2-year-old daughter Juliana (named for Juliana Faesler) was present on stage during most of the public performances.

3. Teatro de La Rendija (Mérida, Yucatán), a professional experimental, body-based and conceptual company, who have their own theater space in Mérida, where they perform and host other companies. For this project, three professional physical theater performers participated. Participants: Raquel Araujo (director), Katenka Ángeles, Rafael Hernández and Alejo Medina. (For discussion of work by Teatro de La Rendija, see Araujo, “Aprendiendo a sembrar Teatro,” Araujo and Castrillón,“Paisaje Meridiano,” Prieto Stambaugh, “Memorias inquietas”).

4. Colectivo Escénico Oaxaca (Oaxaca City, Oaxaca), a community-based collective that specifically engages with Indigenous communities in the surrounding regions, and works with teachers and professors (for example, one professor of environmental science at the Polytechnic College uses theater to work with K-12 children). The collective is based in a house in Oaxaca, and is a location for arts activities and community activities. Participants: Rosario Sampablo (director), Olga Herrera, Itandehui Méndez and 3-year-old daughter Luna, Palemón Ortega, Ángeles Olivares, Federico Ramírez, Manuel Rubio, Jesús Loaeza, Omar Castellanos, Marycarmen Olivares.

5. A-tar (Tampico, Tamaulipas) is a loose ensemble of three performers. Participants: Sandra Edith Muñoz Cruz (director), Víctor de Jesús Zavala Vargas and Sergio Enrique Aguirre Flores. Muñoz is a full-time professional director of theater for the municipal government, directing a youth theater group. She is also involved with the Artistic Direction of the National Theatre Showcase, see Muñoz “Diversidad en escena.”

Distances and directions from Mexico City: Guadalajara, Jalisco, 300 miles west; Mérida, Yucatán, 1,000 miles north east; Oaxaca city, Oaxaca, 230 miles east; Tampico, Tamaulipas is 300 miles north.

23 La Máquina de Teatro. For discussions, see Hellier-Tinoco, Performing Palimpsest Bodies, “Dead bodies/live bodies,” and “Staging Entrapment in Mexico City.”

24 The Humanities in the Community, 1.

25 Lipsitz, “Standing at the Crossroads,” 61–3.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 “Works of expressive culture that seem to indict injustice and dignify the oppressed produce affective pleasures that substitute for social exchange. Once people decide how they feel about injustice, they no longer see a need to do something about it. Instead, they use their feelings of estrangement as proof that they are good people, that their feelings of empathy, sympathy, and pity absolve them of any responsibility to act. Felice Blake and Paula loanide describe this dynamic as ‘feeling good about feeling bad, ’” ibid., 61–62.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 Fabião, “History and Precariousness,” 124.

32 Ibid., 59.

33 Hellier-Tinoco, “Creating Experimental Performance,” 4.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

American Council of Learned Societies. “Frequently Asked Questions.” Accessed September 19, 2018. https://www.acls.org/about/faq/.

Araujo, Raquel. “La simultaneidad en la construcción visual de Calor.” In Des/tejiendo escenas: desmontajes: procesos de investigación y creación, edited by Ileana Diéguez, 105-110. Mexico City: Universidad Iberoamericana y Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, 2009.

———. “Aprendiendo a sembrar teatro.” Paso de Gato, 59 (2014): 84–85.

Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences. The Heart of the Matter. Cambridge, MA: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2013. Accessed September 19, 2018. https://www.humanitiescommission.org/_pdf/hss_report.pdf.

Fabião, Eleonora. “History and Precariousness: In Search of a Performative Historiography.” In Perform, Repeat, Record, edited by Amelia Jones and Adrian Heathfield, 121-35. Bristol, UK: Intellect, 2012.

Heathfield, Adrian. “Then Again.” In Perform, Repeat, Record, edited by Amelia Jones and Adrian Heathfield, 27–45. Bristol, UK: Intellect, 2012.

Hellier-Tinoco, Ruth. “Dead Bodies/Live Bodies: Death, Memory and Resurrection in Contemporary Mexican Performance.” In Performance, Embodiment, & Cultural Memory, edited by Colin Counsell and Roberta Mock, 114–39. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2009.

———. “Staging Entrapment in Mexico City: La Máquina de Teatro’s Reconstruction of the Massacres in Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco.” Journal of the Society for Architectural Historians 73, no. 4 (2014): 474–77.

———. Performing Palimpsest Bodies: Postmemory Theatre Experiments in Mexico. Bristol, UK and Chicago: Intellect and University of Chicago Press, forthcoming.

———. “Creating Experimental Performance: memories/histories, processes/practices” (THTR 187MU & MUS 168P). Syllabus, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, 2018.

Hirsch, Marianne. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

———. “The Generation of Postmemory.” Poetics Today 29, no. 1 (2008): 103–28.

———. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. New York: Columbia, 2012.

———. Postmemory. Accessed September 19, 2018. www.postmemory.net.

La Máquina de Teatro. Accessed September 19, 2018. www.Lamaquinadeteatro.mx.

Lipsitz, George. “‘Standing at the Crossroads’: Why Race, State Violence and Radical Movements Matter Now.” In The Rising Tide of Color: Race, State Violence and Radical Movements, edited by Moon-Ho Jung, 36-70. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014.

Morrison, Toni. Beloved. New York: Random House, 1987.

Muñoz, Sandra. “Diversidad en escena: una muestra de nuestro territorio teatral.” Paso de Gato 59 (2014): 75.

National Humanities Alliance. “About the Humanities.” Accessed September 19, 2018. www.nhalliance.org/about_the_humanities.

Prieto Stambaugh, Antonio. “Memorias inquietas: testimonio y confesión en el teatro performativo de México y Brasil.” In Corporalidades Escénicas. Representaciones del cuerpo en el teatro, la danza y el performance, edited by Elka Fediuk and Antonio Prieto Stambaugh, 216-52. Buenos Aires: Editorial Argus-a Artes y Humanidades, 2016.

Schneider, Rebecca. Performing Remains: Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment. New York: Routledge, 2011.

Stanford Humanities Center. “What are the Humanities.” Defining the Humanities. Accessed September 19, 2018. www.shc.stanford.edu/what-are-the-humanities.

Steedman, Carolyn. Dust: The Archive and Cultural History. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2002.

Strauss, Valerie. “Why we still need to study the humanities in a STEM world.” Washington Post, October 18, 2017. www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet.

Taylor, Diana. The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003.

The Humanities in the Community: 2017 Convening of the Western Humanities Alliance, Interdisciplinary Humanities Center, UC Santa Barbara, Call for papers. Santa Barbara, CA: University of California Interdisciplinary Humanities Center, 2017.

Yépez, Gabriel. “Encuentro Internacional de Escena Contemporánea Transversales.” Paso de Gato 58 (2014): 92–94.