Volker M. Welter

Restoration within Reach: The Miles C. Bates House, Palm Desert, California

On March 26 of this year, the Miles C. Bates House on Santa Rosa Way, Palm Desert, California, became the city’s first historic building that is listed in the National Register of Historic Places (NHRP),1 a decision that automatically also includes listing in the California Register of Historical Resources (Fig. 1). Earlier, on January 11, 2018, the city had already designated the house as a historic landmark; 2 thus within a matter of a few weeks the small house that Walter S. White (1917-2002) had designed in 1954 for Miles C. Bates (1930-1976) went from near obscurity to gaining national, statewide, and local recognition (Figs. 2-3). Coinciding with the end of the 2018 Modernism Week, the annual international celebration of mid-twentieth-century modern architecture in Palm Springs and adjacent communities, the Bates House was successfully auctioned off on February 24 to an architecture firm from Los Angeles.3

Fig. 1. Southeast view of the Miles C. Bates house, 1954-1955, by Walter S. White. (Drawing by Siegfried Knop, Walter S. White papers, Architecture and Design Collection; Art, Design & Architecture Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara. © UC Regents).

The legal situation of the house’s most recent owner, the Palm Desert Redevelopment Agency (RDA), stipulated the unusual sale procedure. When the State of California abandoned for financial considerations the RDAs, which had been a contested tool of local, state-sponsored urban redevelopment, successor agencies were established that were charged with selling their assets for the highest possible price.4 The Successor Agency to the Palm Desert RDA, for example, was obliged to dispose of its assets by latest June 30, 2018. The Palm Desert RDA had acquired the Bates House in 2007 with the goal of redeveloping the land, which is situated opposite the Joslyn Center for senior citizens on the other side of the block. The house had various private owners after Bates sold it in 1962; 5 yet at least since 2007, it stood more or less empty and gradually fell into disrepair.

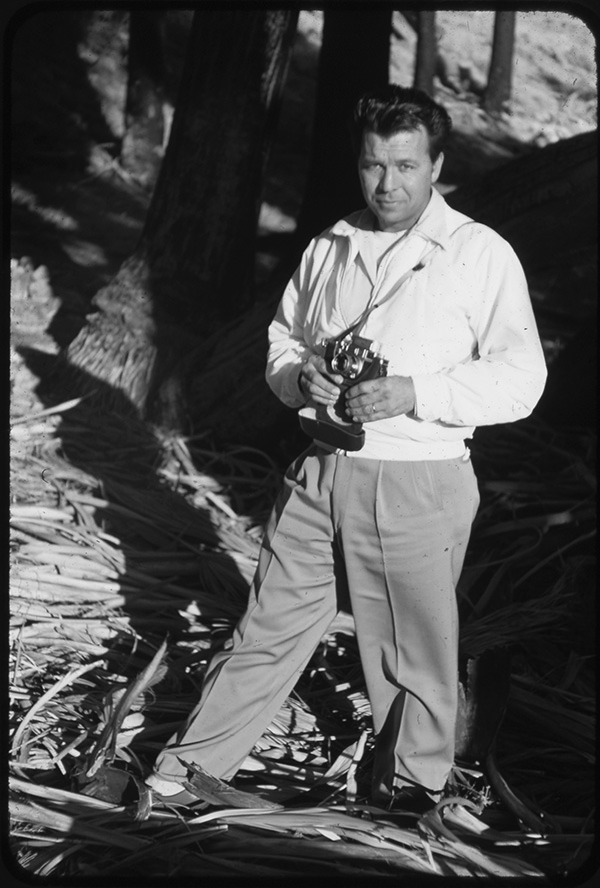

Fig. 2. Walter S. White with camera, c. mid 1950s. (Walter S. White papers, Architecture and Design Collection; Art, Design & Architecture Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara © UC Regents.)

From near ruin to restoration within reach,6 the recent history of the Bates House reads like an architecturally historical rags-to-riches story. It is, however, also one that illustrates how history of architecture can resonate with a local community and even become a rallying point for creating a sense of community. When White moved as a young designer and builder to the La Quinta and Palm Desert area in 1947, he became deeply involved in architecturally shaping the newly emerging, planned community of Palm Desert. Almost seventy years later, a different community formed around the Bates House when its precarious situation became pressing with the forthcoming enforced sale and the possibility that a developer would acquire the lot for the land and not for the unique building that is so closely tied to the early history of the city. The Historical Society of Palm Desert (HSPD) took the lead in having the houses listed in the NRHP, when a successful fundraising effort on and off the Internet allowed the HSPD to commission the research and submission of the NRHP application.7

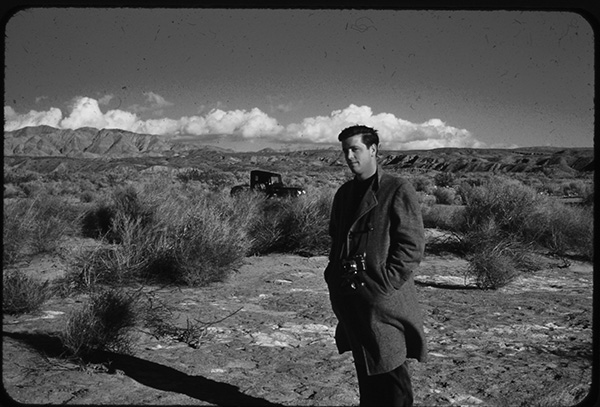

Fig. 3. Miles C. Bates, unknown location, mid 1950s. Walter S. White papers. Architecture and Design Collection; Art, Design & Architecture Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara © UC Regents.

Lectures about the Bates home and open houses drew enthusiasts from near and far to Palm Desert and the building. The HSPD also curated a small exhibition with the support of the Architecture and Design Collection at UC Santa Barbara, which preserves the papers of Walter S. White. This smaller exhibition made up in part for the lack of interest regional museums expressed in showing locally the first ever exhibition on Walter S. White’s architecture that UCSB had mounted in fall of 20158 and that was followed in early 2016 by the first ever book on White.9 Sections of the HSDP exhibition on White’s work in Palm Desert will be integrated into the permanent display on Palm Desert’s history in the local museum the HSPD operates in the city’s former fire house.

The decision by the HSPD to go ahead with an NRHP application was not uncontested.10 The city, legally obliged to sell the Bates House as an asset of the former RDA, for some time preferred for strategic reasons recognition on the municipal level as a historic landmark rather than inclusion in the NRHP. The latter offers national recognition, the former more protection against demolition, among other differences. Yet, the city otherwise supported the preservation efforts, not least with an offer of up to $50,000 to a new owner to help defray costs arising from preserving the house.

Regardless of the now moot back-and-forth over the virtues of one form of listing versus another, it cannot be denied that the Bates House was important for the history of Palm Desert. The quirky appearance of the home recalls homestead cabins, an aspect of the modern settlement of the desert that is often overlooked when the history of Palm Desert is told as that of the Shadow Mountain Club and its neighborhood. Critical histories that pursue preconceived opinions, for example, of the Coachella Valley as a leisure suburb of nearby Los Angeles, likewise do not take into consideration homesteading as a factor in the settlement and the architecture of the desert.11 This essay traces some stages in the lives of White and, to a much lesser degree, Bates, looks briefly at early Palm Desert as a planned community, and discusses at length the architecturally historic importance of the Bates House.

At the outset of his career as an independent designer and builder, White was obliged to sign his drawings with the qualifier “designer, not an architect”; only in 1968 was he finally licensed as an architect by the State of Colorado.12 White did not lack, however, knowledge of how to build houses; born in San Bernardino, California, he had learned construction from his father, who owned a local building company. Rather than pursuing a formal architecture degree, White worked during the 1930s and 1940s for various architects and engineers. Between 1937 and the end of the World War II, he could be found, for example, in the offices of the modernist architects Harwell Hamilton Harris, Rudolf Schindler, and Leopold Fischer. Both Schindler, an immigrant before the Great War, and Fischer, an émigré fleeing from National Socialism, were from Austria.13 White also sought employment with revival-style architects, among them Allen Kelly Ruoff and Clifford A. Balch,14 and engineers such as Win E. Wilson, for whom in the early 1940s he designed prefabricated war housing, using Wilson’s invention of skin-stressed plywood panels. From 1942 onward, White worked as a machine tool designer for Douglas Aircraft Company in El Segundo, California. After the war, he returned to architecture and to life in the desert, and in 1947 took up a position in the Palm Springs modernist architecture firm of John Porter Clark and Albert Frey. In 1949, after eighteen months at the firm, White set up his own construction and design business in Palm Desert.

An outsider to the networks that many architects, critics, and architectural historians forge when at architecture school or in graduate school, White rarely made it into the pages of contemporary professional architectural magazines, and, later, barely onto the radar screens of architectural historians.15 His œuvre does not dovetail easily with categories often employed by architectural history, be they stylistically or aesthetically conceived, socially and economically determined—as in vernacular or anonymous building practices versus architect-designed edifices—or driven by meta-categories such as gender, race, or the social production of space.

A better context in which to place White’s work is the American tradition of individualist, ingenious inventors, tinkerers, and bricoleurs, to use a term that was briefly popular in the architectural discourse of the 1980s. To solve problems, probably ones only an inventor may recognize as existing, or to improve or reinvent established ways of doing things, are some of the possible joys of a life dedicated to inventing. Beside designing houses, White’s legacy as an inventor encompasses, to name only a very small selection: solar updraft towers to solve energy problems; metal hypar roofs to save on costly wooden formworks necessary for casting such roofs in concrete;16 trampoline pedestals for winter Olympians to train during snowless summers; manually revolving windows to adjust the amount of passive solar heat gain to the seasons;17 and a temporary shelter that unfolds from a bicycle trailer.

Miles C. Bates was a client who held an individualist and creative outlook on life comparable to White’s and who was, in addition, independently wealthy. Bates’ enterprising character complemented White’s inclination to experiment with and reinvent architectural construction methods and building elements. Both men’s visions for the Bates House in Palm Desert are well captured in two color perspectives.

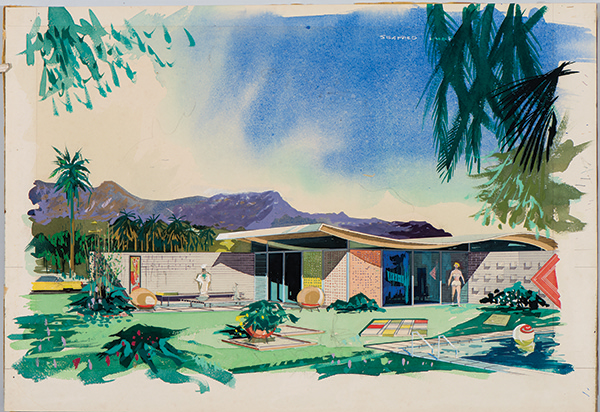

One drawing depicts life in the desert as seen through the client’s eyes (Fig. 4). A beautiful woman in a swimsuit shares the garden with artwork; plants are confined to pots or planters so as not to interrupt the expanse of lawn; comfort chairs, benches, and a pool complement the idyllic scene. When Bates moved to California is not known, but that he came from a wealthy family based in the Chicago area that had made its money with packaging materials makes him an excellent representative of a social class for whom private wealth translated into carefree desert life.18 For Bates this meant driving fast cars—he owned a Mercedes-Benz 300SL with gull-wing doors—dabbling in painting, and, as an avid conga drummer, frequenting bars and nightclubs in Palm Springs.

Fig. 4. Southwest view of Miles C. Bates house, 1954-1955, by Walter S. White. (Drawing by Siegfried Knop, Walter S. White papers, Architecture and Design Collection; Art, Design & Architecture Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara © UC Regents.)

Bates also fancied himself a patron of modern architecture. Walter S. White designed six houses for him, of which only three were built, including a prefabricated holiday cabin at an unknown location in Colorado. Among the unbuilt designs is one from 1952 for a large house with a curved floor plan underneath a similarly curved but also concave roof that was planned for a site in the hills of northern Palm Springs. Yet when a car mechanic crashed Bates’ gull-wing Mercedes,19 family lore and rumor have it that the funds for the Palm Springs house were split between a new car and the much smaller house in Palm Desert.

Figure 1 shows a second perspective that illustrates the architectural idea behind the house, which appears to be almost all roof, the first defense against the light and heat of the desert. From a single anchor point, a concrete buttress that ties a roof beam made from laminated wood to the ground on the garden side of the home, the roof rises to a continuous, undulating movement that only stops at the other end of the building. A second beam rests on top of a wall at the street side of the house; inside, steel posts support both roof beams.

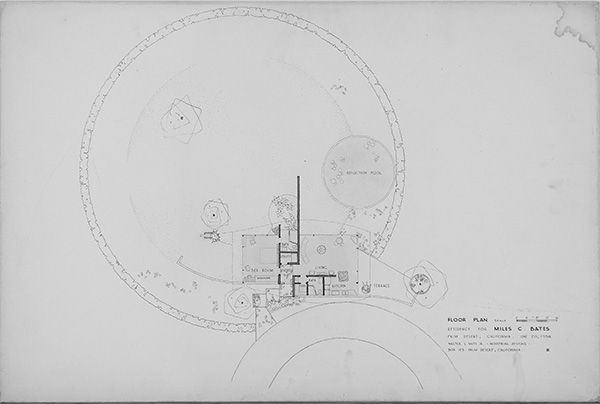

Underneath the roof, transparent and translucent glass walls define the interior spaces, while freestanding masonry walls extend from deep inside far into the outside where they divide the garden into different zones (Fig. 5). Reinforced masonry walls are reduced to a minimum, since they are not needed to hold up a roof that rests on its own support system, and are usually arranged in 90-degree or acute angles in order to stiffen long stretches of masonry in case of earthquakes. The plan of the Bates House somewhat recalls the 1924 design for a country house in brick by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, with its walls extending endlessly outward from the house and even beyond the margins of the drafting paper; perhaps White learned about this icon of architectural modernism when working with such European modernists as Schindler and Fischer.

Yet, White’s primary goals were not to capture abstract space or to form a wave-like roof that mimicked, even if exceedingly well, the silhouette of a distant mountain range. A close look at the roof shows that it is crafted from two alternating wooden components, dowels and bi-concave or “hourglass shapes.” 20 Because the round profile of the one part snugly fits into the concave sides of the other, both together can easily follow the curvature of the supporting wood beams once they are joined and glued into place (Fig. 6). What fascinated White was how to construct such curvilinear surfaces, an interest in making that comes before a form, such as the wave of the Bates House, is determined.

Fig. 5. Preliminary site plan and floorplan of the Miles C. Bates house, 1954-1955, by Walter S. White. (Walter S. White papers. Architecture and Design Collection; Art, Design & Architecture Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara © UC Regents.)

In the post-war period, modern architecture increasingly borrowed industrial methods and materials developed or improved during the World War II by Southern California’s military aircraft production. Initiatives such as the Case Study House program were intended to stimulate innovative designs and construction methods for an affordable domestic architecture for the masses.21 White, however, went the other way with the roof for the Bates House. His patented construction method allowed one to build walls and roofs of almost any curvature,22 and, accordingly, to individualize rather than standardize the appearance of a building. This would broaden the aesthetic possibilities for designers and builders while reducing the parts needed. Using wood, a material that, if necessary, could be shaped in a local lumberyard or even a private backyard, might reduce costs. Finally, the relative simplicity of the construction method could increase the chances of self-building such a roof (or wall) by a skilled homeowner. Simple materials, simplified components, and accessible techniques point to homesteading, in particular the cabins that newly minted landowners often erected by and for themselves in order to meet the legal obligation to improve their homestead within a set amount of time or forfeit the title to the land.

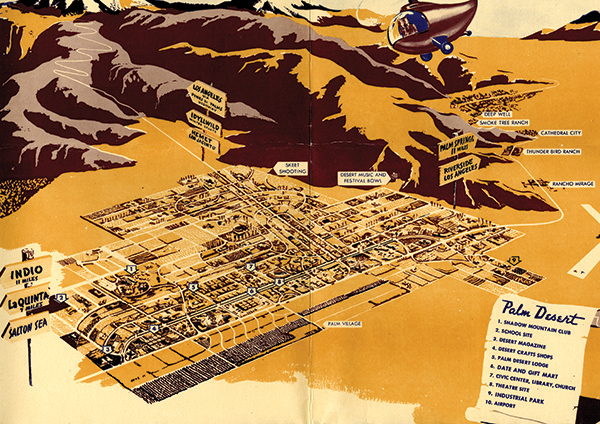

The early history of Palm Desert is to a large extent identical with that of the Shadow Mountain Club.23 The opening of the club in 1948 was a decisive step in the endeavor of Carl, Clifford, Phil, and Randall Henderson, four entrepreneurial brothers, and their financial backers to transform a World War II military base in the desert from a “wasteland to wonderland.” 24 Named Palm Desert, the master-planned development was to be a community of sumptuous houses on generous lots near a family-oriented leisure club, the focus of the new neighborhood. The club was designed by the architect Henry Lawrence Eggers,25 a partner in the office of Gordon Bernie Kaufmann. The members of the community were to build their new houses on territory adjacent to the club; membership came with the purchase of a lot.

The plan was for the majority of houses to be built to the west of the club; the landscape architect Tommy Tomson, husband of the sister of the four brothers, developed a masterplan covering broadly the area between today’s Highway 111 in the north and the Palms-to-Pines Highway in the west (Fig. 7). Multiple-unit dwellings, hotels, commercial and business premises were placed along Highway 111; the club offered leisure facilities including a large pool, restaurants, and a bar, and organized a busy social calendar during the season. Some new lots, especially in the most southern part, were large enough to accommodate private stables for horses; golfing came to the Shadow Mountain Club and Palm Desert only in the 1960s.

At later stages, land even further to the west, across the Palms-to-Pines Highway, and also to the east of the club was subdivided into smaller lots, thus making more obvious a distinction in the size of lots and houses and, accordingly, of social status. In the core area, differences existed but were more subtle: the largest lots were mostly on the south side of Joshua Tree Street and along Juniper, Pinyon, and Ironwood streets. Corner lots were larger in general, and those along curved streets often had distinct shapes in comparison with those on straight streets.26 The eastern- and westernmost subdivisions featured distinctively smaller lots. The Palm Desert Corporation also established and controlled rules concerning the architecture of any building including their style—variations of ranch houses—and size. Detached houses in the core territory had to be at least 1,200 sq. ft. large and garages and porches were to be integrated into the building, but only half of their size could be counted toward the minimum size of the homes.27

Fig. 7. Bird’s eye view of the future Shadow Mountain Club and Palm Desert from an undated promotional brochure. By permission and courtesy of Historical Society of Palm Desert.

When White moved back into the desert in 1947, settling in La Quinta, he was for years the only designer-builder with a design office in nearby Palm Desert.28 As a member of the quickly forming local community, White received many commissions from new landowners, and large detached houses became a specialty of his. Between 1949 and 1959, White designed twenty-five large homes in the core area to the west of the Shadow Mountain Club. Ten of these were planned for, respectively built on preferred corner lots and an eleventh on a larger lot on a curved street. In addition, White designed twenty-two smaller houses for the areas to the east of the club and west of the Palm-to-Pines Highway.29

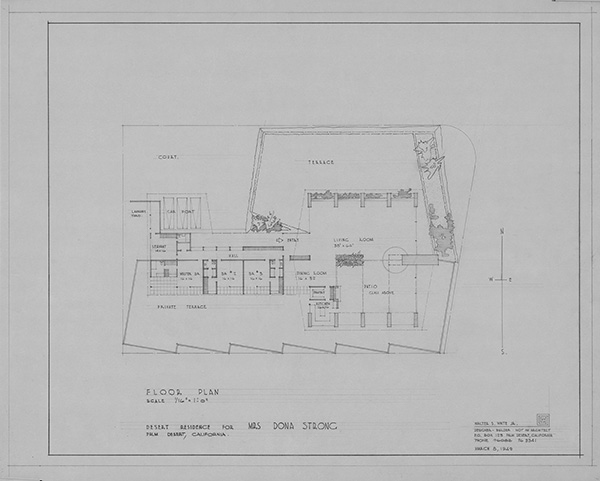

White’s larger homes for the Shadow Mountain Club area are mostly variations of ranch houses, but with a twist. Many of his designs emphasized entertainment and social spaces, often at the expense of bedrooms, which tended to be relatively small and tucked away at the end of wings or even across breezeways offering shortcuts from the street front of a house to its garden space. To cite just one example, on March 8, 1949 White designed a home for a Dona Strong, a client who had acquired a lot on the southwestern corner of the junction of Juniper Street and Burroweed Lane only four days earlier (Fig. 8). The plan focuses on an expansive living room with a free-standing round fireplace and a dining area, together comprising already 3,200 sq. ft., to which a glass-covered, open patio adds another approximately 1,900 sq. ft.30 The unbuilt design illustrates well the kind of generous upper-middle-class and middle-class houses White conceived around the social entertainment needs of their owners if and when these were temporarily in residence during weekends or the season.

Fig. 8. Preliminary site plan and floorplan of the unrealized Dona Strong house, Juniper Street corner with Burroweed Lane, 1949, by Walter S. White. (Walter S. White papers, Architecture and Design Collection. Art, Design and Architecture Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara © UC Regents.)

Palm Desert, the Coachella Valley, and the desert in general, however, also attracted permanent and long-term settlers. Some came for health reasons, others for economic opportunities or drawn by the possibility of homesteading as a way to own and work land.31 Cahuilla Hills on the eastern mountain edge of Palm Desert is a visible reminder of that kind of unplanned development: lots strewn with cactus, rocks, and the occasional abandoned palm tree plantation share the ground with dirt roads leading to cabins and inconspicuous smaller homes; though today many of the houses have mushroomed into large, though architecturally often irrelevant, properties. Bates, for example, owned a small cabin high up on that hillside, which is well preserved by its current owner.

Many of these cabins and similar small homestead houses were self-built. They were erected almost always with whatever materials and construction methods were available, affordable, posed little transportation issues (an important consideration given the isolated location of the building sites), and were easy to work with. In nearby Morongo Valley, for example, in 1947 a schoolteacher built herself a house made from bottles.32 What for homesteaders may have been a necessity, mixing materials, for example, or was an unintended effect, such as a ramshackle appearance or the impression of an (as yet) unfinished cabin, design-oriented builders and architects came sometimes to consider as noteworthy architectural expressions of the free-spirited life of individualist desert settlers.

Historically speaking, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West in Arizona, under construction since 1937, was an early example of an architect-conceived cabin-like desert building. Wright’s many apprentices took this approach further, when they erected their own, temporary shelters, many of them minimal in size, with moveable exterior walls of whatever materials and foldable, space-saving interior elements.33 Closer to Palm Desert, the spider legs with which Tommy Tomson tied to the rocks high above the city a cabin that he had built by bolting together disused railroad ties became elegant outriggers at an early sales office of the Palm Desert Corporation (Fig. 9).34 The latter building White may or may not have designed, but he definitely occupied it at some time together with another local builder.35 Other real estate sales offices were likewise influenced by quickly put-together homestead cabins, their appearance oscillating between such cabins under construction and oversized billboards (Fig. 10).36

Fig. 9. Tomson cabin, Cahuilla Hills above Palm Desert, California, before 1949, by Tommy Tomson. By permission and courtesy of Historical Society of Palm Desert.

Some of these desert buildings inspired by homestead cabins even received the blessing of professional magazines. When the young architect Terry Waters opened an office in Cathedral City in the early 1950s, he erected a transportable edifice made from pipe columns, airplane control cables, aluminum panels, steel beams, and canvas sidings and roof. Whether the flimsy-appearing but sturdy little structure attracted clients is not known, but it guaranteed the hopeful architect publicity in magazines in the U.S. and even abroad.37

When White designed homes outside of the geographical area and the proscribed aesthetics of the Shadow Mountain Club neighborhood, his inventiveness soared. For the Bates House he created a roller coaster roof; above the Alexander House in Palm Springs sailed a concave roof;38 and a house from 1956 for Truman Ratliff—a health-seeker turned farmer in La Quinta—was one vast roof gently rolled out over an almost all-glass box.39 White was a very skillful designer of large houses for the Shadow Mountain Club community, but he excelled when he could design houses that architecturally evoked images of the desert as the home of inventive, creative, and free-spirited human beings.

Fig. 10. Hal Kapp—Ted Smith Real Estate office, Highway 111, Palm Desert, California, c. 1953, unknown designer. By permission and courtesy of Historical Society of Palm Desert.

Seen in this light, the architecture of the Bates house, especially the roof, recalls the contributions these desert settlers made to the city of Palm Desert. When the house was built, it was located not in the “craggily, cactus-studded landscape of the area,” 40 as a recent article in an architectural journal claimed. In fact, it was erected in the then thinly settled northern Palm Desert, far away from the Shadow Mountain Club area. It stood on a clearing that was cut into the rows of citrus groves that still dominated the part of the city that was on the other side of Highway 111.

The happy coincidence that, within a short period of time, the HSPD’s listing efforts, the city’s recognition, and the successful auction all ended positively signals the return of two prodigal sons, Miles C. Bates and Walter S. White, to their community. Equally if not more important is the fact that the architecture of the first Palm Desert building listed in the NRHP is a visible reminder that the city originated in both the middle-class neighborhood around the Shadow Mountain Club and the homes and homesteads elsewhere in the city’s territory and in the desert beyond.

Notes

1 “National Register of Historic Places Program,” National Park Service.

2 “Resolution No 2014-04,” City of Palm Desert.

3 For the auction, see, for example, City of Palm Desert, “Miles C. Bates House” and Foster, “Turn back the Clock and get $50K.” The buyers are Stayner Architects (www.staynerarchitects.com/index/).

4 Greenhut, “California’s Secret Government”; Blount et al., Redevelopment Agencies in California.

5 Lamprecht, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, sec. 7, 11.

6 Federal guidelines for the treatment of historic places distinguish between preservation, restoration, rehabilitation, and reconstruction as four acceptable approaches. These options differ, for example, concerning permissible repairs and alterations that satisfy contemporary needs while maintaining the architectural integrity of a listed site. (See “The Miles C. Bates House—The Fog of War?” Haverkate Blog.) This essay makes no recommendation regarding which of the four approaches is appropriate to the Bates House.

7 The fundraising campaign was supported by the Palm Springs Preservation Foundation, Modernism Week, and many private donors including owners of Walter S. White houses as far away as Colorado Springs. The application was prepared by Dr. Barbara Lamprecht, Pasadena, CA. See Lamprecht, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form.

8 “Finding Aid for the Walter S. White papers,” Architecture and Design Collection; “‘Walter S. White: Inventions in midcentury Architecture,’” Art, Design & Architecture Museum.

9 Welter, Walter S. White.

10 For the local discussion around the house, see, for example, “The Miles C. Bates House—The Fog of War?” Haverkate Blog.

11 For Palm Desert’s history, see Historical Society of Palm Desert, Palm Desert. For the Coachella Valley as a leisure destination and suburb, see, for example, Culver, The Frontier of Leisure.

12 “Colorado State Board of Examiners of Architects,” Art, Design & Architecture Museum. California granted a license in May 1989 (California Architects Board, “Walter Stares White”).

13 In 1959, White and Fisher collaborated again on some projects in the Coachella Valley (Welter, Walter S. White, 11). See also, Bauhaus Dessau e.V., Leopold Fischer.

14 “Allen Kelly Ruoff (Architect),” Pacific Coast Architecture Database; “Clifford A. Balch (Architect),” Pacific Coast Architecture Database.

15 In the 1940s and 1950s, White’s desert architecture was mostly published in daily newspapers such as The Desert Sun or The Los Angeles Times. From the 1960s onwards and especially after White had moved to Colorado, more of his designs were published in professional magazines. See the bibliography in Welter, Walter S. White, 107-108.

16 U.S. Patent No. 3,280,518 Hypar Roof and Wall Construction System.

17 U.S. Patent No. 3,925,945 Heat Exchanger Window.

18 I am drawing here on research by Katherine Papineau, professor at California Baptist University and a former graduate student at UCSB. See also Kaford Papineau, “Miles C. Bates House, Palm Desert,” in Welter, Walter S. White, 64-65.

19 Anonymous, “Motorist Saved Twice in Wreck of Sports Car Here,” 1.

20 Lamprecht, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, sec. 7, 8.

21 See, for example, Smith, Blueprints for Modern Living.

22 U.S. Patent No. 2,869,182 Roof/Wall Construction Method.

23 Historical Society of Palm Desert, Palm Desert, 41-60; Welter, Walter S. White, 30-49.

24 Shadow Mountain Club Sun Spots, issue 52, cover page, Folder CWH—Property—Shadow Mountain Club—Sunspots I, Clifford W. Henderson Papers, Historical Society of Palm Desert.

25 Clifford Henderson, “Memo on financing construction of the club, April 16, 1948,” Folder CWH—Property—Palm Desert Corporation IV, Clifford W. Henderson papers, Historical Society of Palm Desert.

26 “Palm Desert Community Riverside County California, Palm Desert Corporation, Clifford W. Henderson, Founder-President, Tommy Tomson—A.S.L.A., Land Planning Consultant, December 10th, 1945,” Masterplan, Historical Society of Palm Desert.

27 “Declaration of Protective Restrictions Palm Desert, November 7, 1946,” Folder PD—History—Palm Desert Corporation, Historical Society of Palm Desert.

28 Welter, Walter S. White, 34.

29 The figures comprise houses and unrealized designs. See Welter, “The Architecture of Walter S. White.”

30 Welter, Walter S. White, 32, 41.

31 Norris, “On Beyond Reason,” 297–312.

32 Stedman, “Woman Homestead,” 11-12.

33 Pfeiffer and Sidy, Under Arizona Skies, 1.

34 Henderson, “Cabin in the Hot Rocks.…,” 1–12.

35 For a photograph, see Welter, Walter S. White, 34.

36 For one exemplary building, see Historical Society of Palm Desert, Palm Desert, 89.

37 Entenza, “Design Studio by Terry Waters,” 26; Anonymous, “Un padiglione,” 13.

38 The Alexander House was the first building by White that was listed in the NRHP in March 22, 2016 (“National Register of Historic Places Program,” National Park Service).

39 Suzanne van de Meerendonk, “Ratliff Farmhouse, La Quinta,” in Welter, Walter S. White, 84-85. The house was built in 1956 but later demolished.

40 Antonio Pacheco, “Iconic midcentury ‘wave house’ in Palm Desert will be restored by L.A.-based architects.”

Bibliography

Anonymous. “Motorist Saved Twice in Wreck of Sports Car Here.” Desert Sun, September 29, 1955, 1.

Anonymous. “Un padiglione.” Domus, no. 329 (1957): 13.

Anonymous. “The Miles C. Bates House—The Fog of War?” Haverkate Blog, November 27, 2017. Accessed March 31, 2018. www.modernhomesblog.com/2017/11/27/miles-c-bates-house/.

Anonymous. “Allen Kelly Ruoff (Architect).” Pacific Coast Architecture Database. Accessed April 2, 2018. http://pcad.lib.washington.edu/person/96/.

Anonymous. “Clifford A. Balch (Architect).” Pacific Coast Architecture Database. Accessed April 2, 2018. http://pcad.lib.washington.edu/person/290/.

Architecture and Design Collection; Art, Design & Architecture Museum; UC Santa Barbara. “Finding Aid for the Walter S. White papers, circa 1935-2002.” Accessed April 8, 2018. Online Archive of California. http://pdf.oac.cdlib.org/pdf/ucsb/uam/193_WhiteWalter_EAD.pdf.

Art, Design & Architecture Museum; UC Santa Barbara. “‘Walter S. White: Inventions in midcentury Architecture,’ September 12, 2015 to December 6, 2015.” Acessed April 6, 2018. www.museum.ucsb.edu/news/feature/387.

Bauhaus Dessau e.V., ed. Leopold Fischer: Architekt der Moderne. Dessau-Roβlau: Funk Verlag Bernhard Hein e.K., no year [2007].

Blount, Casey, et al. Redevelopment Agencies in California: History, Benefits, Excesses, and Closure. Working Paper No. EMAD-2014-01. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, January 2014. Accessed March 31, 2018. www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/redevelopment_whitepaper.pdf.

California Architects Board. “Walter Stares White.” Accessed April 3, 2018. http://www2.dca.ca.gov/pls/wllpub/WLLQRYNA$LCEV2.QueryViewP_LICENSE_NUMBER=20210&P_LTE_ID=1010.

Clifford W. Henderson Papers, Historical Society of Palm Desert.

Culver, Lawrence. The Frontier of Leisure: Southern California and the Shaping of Modern America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Entenza, John. “Design Studio by Terry Waters.” Arts & Architecture 72, no. 1 (January 1955): 26.

Foster, R. Daniel. “Turn back the Clock and get $50K: Palm Desert will pay a Buyer who will agree to restore a 1955 Landmark.” Los Angeles Times, February 17, 2018, J25.

Greenhut, Steven. “California’s Secret Government: Redevelopment agencies blight the Golden State.” City Journal, Spring 2011. Accessed March 31, 2018. www.city-journal.org/html/california’s-secret-government-13378.html.

Henderson, Randall. “Cabin in the Hot Rocks….” Desert Magazine, March 1949, 1–12.

Historical Society of Palm Desert. Palm Desert: Images of America. Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2009.

Lamprecht, Barbara. National Register of Historic Places Reg. Form [for the M.C. Bates House], not dated [2017]. Accessed March 31, 2018. www.pspreservationfoundation.orgpdf/CA_RiversideCounty_MilesCBatesHouse_DRAFT%2011.27.2017.pdf.

National Park Service. “National Register of Historic Places Program: Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 3/12/2018 through 3/29/2018, February 21, 2018.” Accessed April 3, 2018. www.nps.gov/nr/listings/20180330.htm.

National Register of Historic Places. “Alexander, Dr. Franz. Residence.” National Register of Historic Places, March 22, 2016. Accessed April 7, 2018. www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/16000093.htm.

Norris, Frank. “On Beyond Reason: Homesteading in the California Desert, 1885–1940.” Southern California Quarterly 64 (Winter 1982): 297–312.

Pacheco, Antonio. “Iconic midcentury ‘wave house’ in Palm Desert will be restored by L.A.-based architects.” The Architects’ Newspaper, February 26, 2018. Accessed April 4, 2018. www.archpaper.com/2018/02/miles-c-bates-house-palm-desert-finds-buyer-stayner-architect/.

Palm Desert, City of. “Resolution No 2014-04 Historic Landmark Designation, January 11, 2018.” Accessed March 31, 2018. www.cityofpalmdesert.org/home/showdocument?id=22639.

Palm Desert, City of, Dept. of Public Works. “Miles C. Bates House.” Accessed March 31, 2018. www.cityofpalmdesert.org/our-city/departments/public-works/milesbateshouse.

Palm Desert Corporation Papers, Historical Society of Palm Desert.

Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks, and Victor E. Sidy. Under Arizona Skies: The Apprentice Desert Shelters at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West. San Francisco: Pomegranate, 2011.

Smith, Elizabeth A. T., ed. Blueprints for Modern Living: History and Legacy of the Case Study Houses. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999.

Stedman, Melissa Branson. “Woman Homestead.” Palm Springs Villager, October 1947, 11-12.

Walter S. White papers, Architecture and Design Collection; Art, Design & Architecture Museum; University of California, Santa Barbara.

Welter, Volker M. Walter S. White: Inventions in Mid-Century Architecture. Santa Barbara: University of California, Santa Barbara, 2016.

———. “The Architecture of Walter S. White.” Online Map. 2015. Accessed April 4, 2018. www.google.commaps/dviewer?hl=en&mid=1LLnrgLL-M83P-cP7euItmvtFIWw&ll=37.69994985991138%2C-99.32792834999998&z=4.

White, Walter S. 1955. Roof/Wall Construction Method. U.S. Patent No. 2,869,182, filed March 15, 1955, and issued January 20, 1959.

———. 1959. Hypar Roof and Wall Construction System. U.S. Patent No. 3,280,518, filed October 6, 1959, and issued October 25, 1966.

———. 1973. Heat Exchanger Window. U.S. Patent No. 3,925,945, filed November 23, 1973, and issued 16 December 1975.