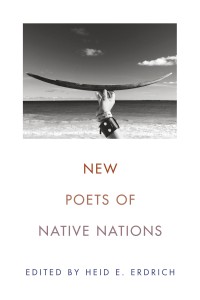

New Poets of Native Nations

Edited by Heid E. Erdrich

Graywolf Press, 2018

Reviewed by Will Cordeiro

Heid E. Erdrich has edited a superb and overdue anthology showcasing the diversity of new Native American poetry, though she claims upfront that so-called “‘Native American poetry’ does not really exist.” While the authors in New Poets of Native Nations are members, citizens, or descendants of at least one of the 566 indigenous tribes or nations in the United States, none are “Native American” alone: they also identify as multi-racial, queer, Mormon, two-spirit, male, female, urban, activists, academics, artists, and many other things besides.

Likewise, the poetry here presents an astonishing multiplicity of voices, aesthetics, and formal range. Erdrich’s underlying point is that, just as each indigenous nation has its own traditions and lifeways, the poets included in the anthology express a variety of concerns, intersectional identities, and styles.

Erdrich’s selection of only twenty-one poets is symbolic: all of the poets published their first book in the twenty-first century. Using this criterion, however, several important and established Native poets have been left out, including Sherwin Bitsui, Joan Kane, Orlando White, Tanaya Winder, Santee Frazier, and Erika Wurth. Other, younger poets who had not yet published their first full-length collection by the anthology’s release date—Michael Wasson, Jake Skeets, or Heather Cahoon, to name a few—are also not included.

Instead, most of the poets Erdrich selected have one or two books out, usually published with small or university presses. While a few well-known writers such as Natalie Diaz and Layli Long Soldier crack the lineup, the bulk of this anthology will likely produce many discoveries for mainstream readers, even those devoted to contemporary poetry, thus bringing more widespread recognition to deserving authors.

For me, these discoveries included Brandy Nālani McDougall’s delightfully subversive “On Cooking Captain Cook,” Margaret Noodin’s bilingual Anishinaabemowin and English poems, Sy Hoahwah’s lapidary images (“I carve my name / on the moon’s teeth”), and M. L. Smoker, who laments her own complicity in the Assiniboine language’s dying out. Smoker implores, “Hold me accountable” even as she attempts, in other poems, to travel home “across the windblown graves” of the reservation backroads where “the cat hunters drive with mannish glory / and return along, gun still oil-shined and unshot” among “the lilting sway of grasslands.”

In contrast to Smoker’s images of reservation life, Tommy Pico admits to feeling more at home in New York City as a gay man immersed in pop culture and social media feeds. He “can’t write a nature poem / bc it’s fodder for the noble savage / narrative.” His poetry instead juxtaposes funky, artificial imagery and glib anecdotes that take suddenly serious turns. He says, for example, a “jellybean moon sugars at me” and recounts how:

Once on campus, I see a York Peppermint Pattie wrapper on the ground,

pick it up, and throw it away. Yr such a good Indian, says some dick

walking to class. So,

I no longer pick up trash.

Similarly, Karenne Wood challenges the stereotypical expectations placed on Native Americans, ending a poem with the snarky jab, “Time to weave a basket, or something.”

As with much literature in this moment, the overwhelming majority of these Native poets display an acute political consciousness. One of Craig Santos Perez’s poems offers the point-blank assertions, “Guam is expected to homeport the Pacific fleet… Guam is a target.” Another of his poems, itself an agglomeration of spindrift fragments, asks:

// in the sea, plastic multiplies

into smaller pieces, leaching estrogenic and toxic

chemicals // if [we] cut open the bellies of whales

and large fish, what fragments will [we] find

Analogously, dg nanouk okpik’s remarkable “neuron-zipped words” decry the “distortion and effects of the warming earth” on arctic taiga, punning on “Bush laws,” while Tacey M. Atsitty’s “Paper Water” plays on the “X” on a contract’s signatory line, at once abrogating Navajo water rights and attesting to the erasure of a people, crossed-out by government treaties and blinded by a stitch-mark “across their own eyelids.”

The anthology, while showcasing the work of many younger poets from Native Nations, at the same time acts as a revealing cross-section of contemporary American poetry’s invigorating diversity. Whereas the majority of the poets offer scathing critiques of what Trevino L. Brings Plenty terms “the many histories of removal” and genocide that indigenous people have faced, the book’s organizing premise nonetheless situates their work within a national—that is, American—dialogue. These poems, then, not only challenge readers’ notions of “Native American Poetry,” but also their assumptions about the meaning of that designation’s constitutive terms. Eric Gansworth asks, “in which language and world view / do you form your first / impression.” The strength of this anthology, however, is in its juxtapositions of different languages, worldviews, and impressions, offering us a vibrant and necessary conversation.

Will Cordeiro has work appearing or forthcoming in Best New Poets, Copper Nickel, DIAGRAM, Fourteen Hills, Nashville Review, Poetry Northwest, Sycamore Review, Terrain.org,The Threepenny Review, Zone 3, and elsewhere. He lives in Flagstaff, where he teaches in the Honors College at Northern Arizona University.