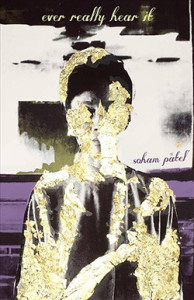

Soham Patel’s ever really hear it, winner of the 2017 Subito Prize, takes an innovative approach to lyric poetry’s origins: the creative entanglement of poetry and music. As with Sappho’s lyrics, absent music structures Patel’s poems, and she sings along, talks over, and responds ekphrastically to this submerged soundtrack. Patel’s book begins with an epigraph from James Baldwin: “All I know about music is that not many people ever really hear it.” In dense and deft lyric sequences, Patel asks us to inhabit what it would mean to “really hear it” while also acknowledging the ways that music itself is ungraspable. Her poems are often untitled and sparsely punctuated, creating a sense of unboundedness across the collection. In these lyric suites, times and places flow into each other, as Patel considers identity, desire, consumption and performativity through meditations on musicians, places, and artifacts like the jukebox and steamboats. Although Patel’s speaker does not appear in this book as a musician, she does “sing along” to the songs she invokes, and sometimes she even begins to operate instruments: “i hold the flute as we walk. i do not put it in my mouth but cannot help not to hold a finger over every hole. i lift one up. one at a time.” In this image, and throughout the book, Patel seems to draw the breath of the world into her instrument, channeling diverse histories and voices. While Patel’s work is exuberantly fluid, set pieces do surface in this collection, especially around figures of women musicians. A powerful “she” weaves through these poems; she may be a single person, a muse, or a series of characters. She first appears as a performer who “launched her pick into the crowd,” a triumphant musician in a moment of breathless intimacy with the speaker-as-audience: “When she opened her picking hand I raised mine as a way to say pick-me-pick-me.” Another suite describes a woman with almost superhuman power: “She used my head like a revolver/ We crushed shine into the listeners.” A recurring character, “the girl/ with the lace/ spilling delicate/ from the fringes/ of her denim skirt,” seems to be a beloved. Sometimes the woman in these poems is capable of naming the world through song: “hepcat casts her calls/ as versions of a name// i and I and I and i…” Is the speaker being redefined by this singer who “casts her calls?” Does this musician’s song transform the speaker’s own relationship to her “I”? Although this poem warns us, “it’s never just about a girl,” the poems in this book are always, somehow, concerned with human connection. There is a tender intimacy at the center of this ambitious, wide-ranging book: “friendship avenue/ rocks quiet tonight.// leaf falls aren’t lonely/ lover, neither are we.” Meanwhile, Patel’s language moves us through swerves of sound and syntax. The dense musicality of her poetry strives to “translate” what she calls the “structure” of musical sound, whether she is transcribing a “one-two-three-four-and-uh-one-and-uh-two-and-uh-three-and-uh-four” or creating her own language’s rhythms. Her poems navigate forms as disparate as prose blocks and sonnets, including commentary on their sonic and formal moves: “ending on a weak beat/queers the feminine fleshed.” Near the beginning of the book, Patel writes, “A lyric is a way of saying in some other language.” Reading ever really hear it, I feel in the presence of a new language, and Patel’s poems boldly transform speech so that even “breath has a music all its own.”