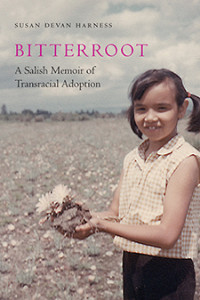

Bitterroot

Susan Devan Harness

Published by University of Nebraska Press

Reviewed by Phillip Barcio

For generations, Americans have proudly embraced the notion of the United States as a melting pot—a utopian republic where members of every culture on Earth live in harmony, working together to roll out the destiny of a shining, unified nation.

Bitterroot, by Susan Devan Harness, reminds us that the true intentions behind that phrase—ethnic and cultural “melting”—are not as idealistic, nor harmonious, as the American mythos implies.

The book recounts the true story of Harness’s journey to construct her identity in the aftermath of her transracial adoption. Born Vicki Charmain to a Salish mother on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Pablo, Montana, Harness was removed from her birth family by Child Protective Services when she was 18 months old because of her mother’s alcoholism. She was adopted by a white couple who raised her in conditions hardly more secure than those from which she was extracted, all the while hiding the truth about her birth parents, and prejudicing her against the culture of her ancestors.

Structured more like a diary at times than a memoir, the narrative unfolds in a plain-spoken way, through which the full depth of the author’s struggle is revealed. As she suffers relentless harassment, an attempted sexual assault by her abusive, manic-depressive, alcoholic adoptive father, and hundreds of sleepless nights tending to her adoptive mother’s psychotic episodes, Harness strives in near total isolation for the courage to connect with her indigenous roots. When she finally does find her people, she learns bigotry flows in both directions, as her new acquaintances, who were raised on the reservation, call her an apple: “red on the outside, white on the inside.”

Alongside this deeply personal story of alienation, disappointment, and ultimately enlightenment, a second, broader narrative unfolds in Bitterroot—that of forced transracial adoptions: part of white America’s intentional effort to subvert Native cultures by assimilating tribal members into the larger American society.

The Indian Adoption Project operated between 1958 and 1967 and was administered by the Child Welfare League of America, using funds from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the U.S. Children’s Bureau. Those who implemented the program expressed righteousness in their intent. They believed they were saving endangered native children by removing them from troubled homes on the reservations and placing them with white families. But as Harness’s story points out, the program was poorly run, blind to its own hypocrisies and failures, and anything but righteous.

The dichotomy Harness unearths in Bitterroot is not new. In 1909, when Israel Zangwill premiered his play The Melting Pot in Washington, DC, the work was lauded for its depiction of a peaceful world freed from racial and ethnic hatred. As an alternative to all-out war, perhaps cultural homogeny is an improvement. Yet Harness shows us the excruciatingly insidious, dark side of the melting pot: the constant, official, institutionalized pressure on every resident of America to forget their history, eradicate their individuality, and become the same.

Though the specific circumstances of Harness’ struggle may be uncommon ground for most readers, her story is full of universalities. For each of us, identity and culture are mental constructs. If we give others the power to tell us who or what we are or where we belong, we doom ourselves to feelings of confusion and inadequacy, and surrender our liberty. And yet, as Harness elucidates, even if we claim the right to construct our own identity, that, too, can become an indomitable chore.

The most optimistic note Bitterroot sounds is thus steganographic. The book takes its name from the bitterroot plant, a desert flower native to the northwestern United States that is considered a culinary delicacy, and a rare and difficult prize to procure. Its botanical epithet, lewisia rediviva, contains infinite hope—rediviva: from Latin, meaning “to be restored to life”—an ancient reference to the ability of plants, or perhaps people, or even nations, to regenerate, even after their roots appear to have died.