Michele Bury, Vivian Price, Ellie Zenhari

Visual Narratives and Political Awareness

Fig. 1. Along with instructor Jorge Cabrera, Social Justice and Labor Class walks along

Avalon Blvd. by the toxic mounds of dirt at Jordan Downs Housing Complex.

(Photo by Dan Cuthbert, 2015)

Our study looks at two cases of socially engaged photography in which students tell community stories through images, although in quite different ways. We use the term “socially engaged photography” in reference to the practices of utilizing culture as a participatory form of social interaction and expression.1 Socially engaged art (SEA) depends on interaction for both artistic and social purposes, a combination of art and social science disciplines: “SEA is a hybrid multi-disciplinary activity that exists somewhere between art and non-art…. SEA depends on actual—not imaginary or hypothetical—social action.” 2

The first case is a set of posters and artworks depicting life in Watts, California, that was produced in collaboratively taught classes and were displayed in a series of exhibits in Watts and at our university as part of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Watts Rebellion of 1965. The second is a series of photographic reenactments and interactive photographic practices that were engaged in during an annual Labor, Social and Environmental Justice Fair on our campus.

In each project the photographic storytelling was meant to evoke an understanding, a gateway into experiences of others, and in both cases the culminating work was embedded in large public events. Narrative projects often evoke identification and empathy,3 but these also inspired political awareness by expressing how communities struggle for justice against oppression. Our description and analysis consider how the visual narratives in both projects were created and displayed or performed to reflect on their process and impact.

We interrogate the work with the notion that art-making creates embodied forms of knowledge.4 This embodied knowledge contributes to producing an impact that can go beyond the aesthetic appreciation of an object, or in this case, a visual narrative. Degarrod asserts that both the body and a person’s emotions are engaged by their “interactions with the artworks, and that viewers, artworks, and environments are all mediators of the experience of knowledge.” 5 In our discussion, we consider how not only the audiences for the work, but also the artists, that is, the students who worked with community to capture images to tell stories, developed experiential knowledge that they invested in their work. Likewise, the faculty who initiated and participated in the collaborations and organizing the exhibits developed emotions that were channelled into the visual narratives and exhibits. This idea of embodiment of knowledge implicated in many phases of the making as well as the displaying of the work in both community and university venues helps to explain the power of this process.

Similarly, the notion of embodiment and its power of creating emotion is one that is relevant to the second series of visual narratives. The reenactments employ the performance of iconic images to evoke empathy for social movements in the youth who took on the positions of protesters, holding simulations of picket signs and banners and using other props; striking a symbolic pose in the case of the Rosie portraits; joining up their faces with the face of a renowned organizer in a half-portrait. In the spirit of Boal, the creator of the Image Theater, the purpose of which was to give space to people to act out ideas and conflicts rather than to depend on words to communicate,6 these performances tap into the notion that the physical body and the mind work together to produce feeling. Considering how these photographic practices were part of a larger event and set of activities and interactions around the theme of social justice is also important to help understand the potential of this project. Therefore, we note that the events were a form of “public pedagogy” 7 that interrupted stereotypes about Watts and provided counter-narratives of social justice protests.

Visual Narratives and the Year of Remembering Watts 1965

The fiftieth-year commemoration of the Watts Rebellion on August 11, 2015 was an internationally recognized event, an anniversary that was covered intensely—if briefly—by radio, print, television and social media. California State University, Dominguez Hills (CSUDH) embraced the anniversary of the Watts Rebellion in recognition of the historical events that contributed to California Governor Pat Brown’s decision to locate the campus in close proximity to the people who were demanding justice. As noted in our university website, “Following the Watts Rebellion, Gov. Pat Brown visited the area and determined that the Dominguez Hills site in the soon-to-be City of Carson would provide the diverse, mostly minority population in nearby urban neighborhoods with the best accessibility to a college education.” 8

This nearly lost footnote of history became a major theme for the campus and reinvigorated a historic bond. The university administration hailed ongoing relationships between CSUDH and Watts. Students increased their interactions with community organizations and with people who lived, worked, and governed Watts. Folks from Watts came to the university, galvanizing the development of a deeper relationship. For many of us, the relationship centered explicitly around fighting racial injustice and valuing community creativity. Reinforcing the historic mission of the university was a political assertion. Fifty years after the event, remembering the Watts Rebellion at the university was a reminder of the historic mission on which CSUDH was founded: to provide quality affordable education to the underserved and racially targeted communities surrounding the campus.

Watts is a community that is a fifteen-minute drive from our university. Over ten percent of our students live in Watts, and many have family there or come from neighborhoods with similar socio-economic conditions. The history of Watts is one of a proud interracial community in the 1920s that became the target of poor public policy. Racial profiling and police brutality were clearly understood in Watts in 1965, when a police traffic stop was the trigger for folks in Watts to fight for their voices to be heard.

Activist faculty viewed the anniversary year as a way of reinforcing the mission of our campus. In the face of an upcoming contract fight in Fall 2014, faculty union leaders framed demands along with students protesting a fee raise as integral to preserving the People’s University (the CSU system as a whole), focusing on our campus in particular, as grounded in the history of the rebellion. Community leaders joined faculty and students in participating in a large event, and the president of the university was invited and addressed the audience as well. Soon afterward, the university administration called for the creation of a year-long commemoration that included national speakers, exhibits, films and a campus dialogue.

Organizing Photography and Art Exhibits

Professor Zenhari was selected by a Watts Rebellion subcommittee to shoot photographs for the exhibit Watts Then and Now, scheduled to open on the anniversary date of August 11, 2015 in the University Cultural Arts Gallery and curated by a committee that included Michele Bury, Greg Williams, Kathy Zimmerer and several administrators. There was to be a student show that Zenhari would curate to open the following February. Since Zenhari teaches in the Art and Design Department and Price teaches in an Interdisciplinary Studies and Labor Studies Program, we discussed how to involve both areas of study as well as our curriculum for students.

In order to create a meaningful community-engagement project, the first priority was to build relationships. With the fame of Watts as a pinnacle of resistance and an ongoing site of oppression, the town attracts people who may not be willing to commit to a long-term relationship. As Helguera notes, “Artists who are inexperienced in working with communities see them in a utilitarian capacity—that is, as opportunities by which they may develop their art practices—but they are ultimately uninterested in immersing themselves in the universe of the community, with all its interests and concerns. This detachment of the artist may make the participants feel as if they are being used instead of like true partners in a dialogue or collaboration.” 9

Our methodology was to utilize social inquiry, community collaboration with students and artistic expression to promote a series of exhibits as well as other activities initiated by community leaders, such as Town Halls in Watts. For us, the exhibits became a way of expressing ideas that students and community shared with each other, a public way of communicating the resulting dialogues about creativity and resilience as well as environmental racism, public housing and associated issues.

Price began visiting Watts in 2015 and taking her students on field trips she arranged with local community organizations. Zenhari accompanied Price and her class on both visits and began taking photographs for the exhibit. They returned throughout the spring, and by June, Price and Zenhari met Tim Watkins, CEO and President of WLCAC (Watts Labor and Community Action Committee), as well as several other community leaders. John Jones III was the City Councilman’s Watts deputy, and he showed Price and Zenhari around the projects that make Watts the town with the highest concentration of public housing in the Western United States. Watkins guided Zenhari to take photos of the pride of Watts but also to capture the environmental degradation. He viewed our school as a partner who showed the intention of building a relationship, rather than taking what we could and then disappearing to build a collection or publish a study without a reciprocal relationship.

Two Initial Exhibits

Watts Then and Now opened within days of each other in two spaces, on the anniversary of the rebellion. Watkins showcased a mirror exhibition of Zenhari’s photographs at the Cecil Ferguson Gallery, which had been in disuse for a number of years. It was exciting to see it come to life for the anniversary, together with the work of other artists and documentation of the Pioneer Club, the longstanding group of people who lived in Watts for decades and had monthly meetings at the Center.

Watkins was open to considering how students could learn from working with WLCAC on community issues. It was this engagement that led to the class that produced posters that were included in the second, student exhibit, which also was mirrored at WLCAC and at the university. While listening to the analysis of how Watts became the object of poor public policy, Price worked with Watkins to shape the collaborative class project. Watkins explained the exploitation of Watts: the freeways and conduits that moved oil and the rail, airways and trucks that crisscross the hub of the city that is Watts, without compensation for the pollution and toxic contamination they left behind under the residences, the schools, the playgrounds. Price learned that two other groups were addressing tenant issues in the north end of Watts, in Jordan Downs, a housing project that was undergoing gentrification. Genrification involved the decontamination of an old steel factory site, also the former site of a smelter, in order to create a mixed-use upgraded housing complex that might displace many of the present residents. Two organizers, Thelmy Perez, of LA Housing Is a Human Right, and Monika Shankar, of Physicians for Social Responsibility, came to meet Tim Watkins, and we all began working together on issues of toxic contamination in Watts. Jorge Cabrera, instructor for the course “Social Justice and Law” (SJL), joined the group, and we mapped out on a weekly basis how the course would be structured to educate students about fair housing law and environmental justice, with all of the community organizers serving as teachers and guides. Watkins brought in Dr. Ernie Smith, a professor and pediatrician at Drew Medical School, who was instrumental in the struggle to bring to light the impact of toxins seeping from the earth into the Watts-Willowbrook housing at Ujima Village, which was finally shut down in 2011.

The university supported the class project by renting a bus for three tours for the fall classes, two for the SJL class and one for Zenhari’s Photography class, which also began studying Watts. These classes ran during the fall of 2015. Students from the SJL class were so involved in community activities that after the series of bus trips were finished, they met on their own to visit the Center.

During that fall semester, Zenhari closely worked with both beginning digital graphic and photography students and helped them develop a cohesive and reflective body of work about what they learned about Watts through field trips and assigned class readings as well as short written reflections. Price visited the photography classes as a guest lecturer and provided a context for the history of the rebellion. Many did not know that much about the history of the rebellion or heard about it primarily as a “riot,” and a few had never heard about it at all.

While Zenhari linked the class assignments in her art classes with the production of images for a February show, we did not recognize that the SJL class could also create images as part of their service learning until well into the class, when we then consciously integrated this component into the curriculum. Zenhari created a manual on how to use photos to promote social change and presented these materials at a workshop for the SJL class held at WLCAC on creative and technical tools for creating compelling photo narratives using a cell-phone camera. The class was joined by people invited by our community partners: students from Jordan Downs High School and residents of Jordan Downs Housing. Workshop participants took photos with their cell phones, while Zenhari guided them with hands-on feedback.

Meeting the SJL students in Watts several times took students out of the classroom and brought us together to learn the history of the area and the present challenges through the voices of community members and leaders.

Our community partners, LA Housing Is a Human Right, Physicians for Social Responsibility, and WLCAC, were themselves working together during the planning for the class. All were involved in exposing patterns of toxic contamination in several housing complexes in Watts and the railroad right-of-way, and were putting pressure on agencies to do the right thing for the people of Watts. Inspired by Watkins, the groups, together with CSUDH and Drew Medical, formed the Better Watts Initiative. We planned a large Town Hall to take place in mid-December 2015 and envisioned a new photo and map exhibit as a way to educate visitors and residents about the extent and nature of soil pollution.

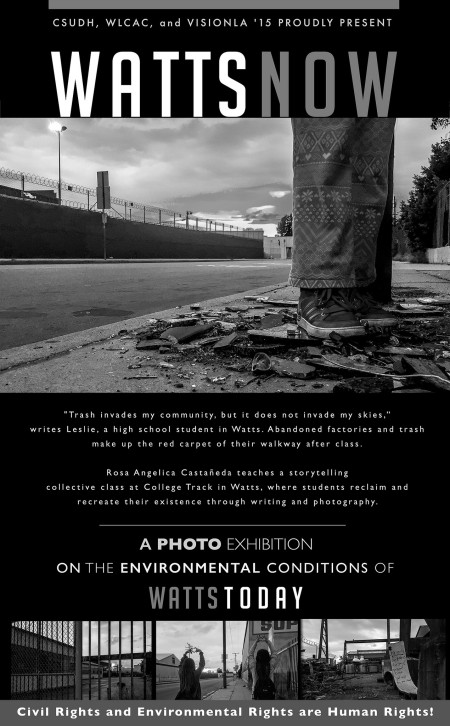

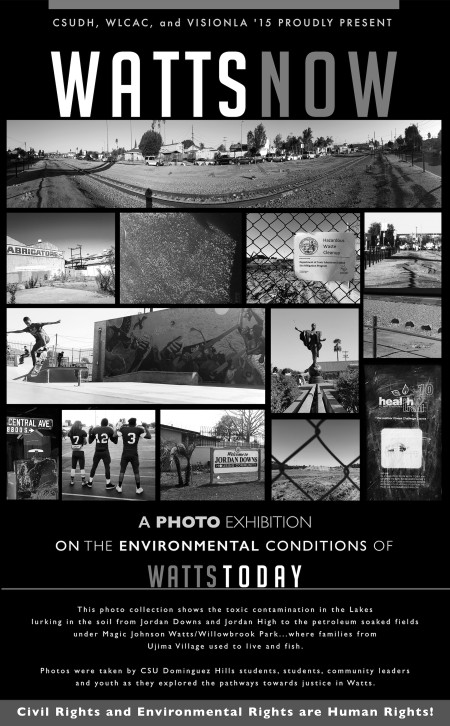

We recognized the power of the images students were taking to represent their perspectives on their embodied experiences. The exhibit included two posters created by Zenhari that emerged out of the SJL class. One poster featured Watkins’ images of soil contamination of railroad track right-of-ways, combined with cell-phone photography by the SJL students who documented their visits to toxic sites in Watts and also by several high school students. In addition, Zenhari created a poster of images contributed by Rosa Angelica Castañeda, an artist whom we met through the class and who worked with youth at a non-profit educational organization in Jordan Downs. Castañeda and her students were among the visitors to the WLCAC December exhibit.

Fig. 2. Watts Now poster with images by Castañeda’s College Track students. (Poster designed by Ellie Zenhair, 2015, California State University Dominguez Hills Library, Special Collections.)

Fig. 3. Toxic contamination in Watts with images from Watkins, community, and students photos. (Poster designed by Ellie Zenhari, 2015, California State University Dominguez Hills Library, Special Collections.)

This third exhibit marked a deeper connection between CSUDH and the Watts community. It signified a profound collaborative social interaction among community groups, local youth, and DH faculty and students. The opening was timed to coincide with the last day of the SJL class. This group sharing provided a thoughtful space for students to share their feelings and then move into the public opening. Watkins guided students and visitors through the first space of the gallery, where Zenhari’s photo wallpaper and the posters introduced the themes of the show. He narrated the sites of environmental degradation that had been hidden from residents in Ujima Village. Dr. Ernie Smith from Charles Drew University guided the group through images and maps and told his story of how the Community Black Health Task Force were critical players in exposing the damage that they believed was being caused by what turned out to be a leaking tank farm with known toxic plumes lying under the residential project. Perez and Shankar finished up the tour of the exhibit by showing the images of Jordan Downs housing complex and the high school that ringed the old steel factory and smelter site.

DH students from the SJL class communicated the deep impact on them of the field trips, learning from community folks, involvement in the art displayed in the show and the culminating tour. They spoke to one another in the final session about how they had become more aware of the dangers that they and their families in Watts and similar areas were exposed to and how outraged they were about the neglect and hidden dangers faced by low-income communities of color. One student noted that the experience helped her decide to become an environmental lawyer. Another said he was planning on investigating the area adjacent to Watts, his home community of Lynwood, another site of post-industrial residential development.

The Impact of the Visual Narrative Art-Making on Participants

The fourth exhibit marked another phase in our project. Photography, motion graphic, studio and design students from several classes produced posters, videos, drawings and photographs for the “Watts Now” Collaborative Student Exhibition in February 2016. Students from an English class also wrote poetry that was displayed at the exhibit, as were the SJL students’ poster and a video made by Price’s earlier class, “Making Connections.” 10 The opening was well-attended, and once again students brought family members and their friends to show off their work. Tim Watkins spoke at the event, motivating students, a number of whom asked how they could work with WLCAC.

Students wrote reflections that communicated how transformative it was to connect with community and how it had helped them learn about the power of photo narratives to capture and spark a conversation about issues of social justice. One student wrote that she appreciated the “field trip opportunities to connect social issues to photo narratives to create stronger projects that encompass topics outside of just creative art,” and she also remarked, “Professor Zenhari has really taught the power of storytelling through photography to allow oneself to become an artist that strives to include a message for change or awareness on topics relating to the surrounding community.”

The field trips, the making of the photos and the collaborative projects engaged the students in ways that involved their bodies and their emotions on a profound level. The photo- and art-making were media that allowed students to express their ideas and feelings and share these with audiences in Watts and at our university. The exhibits provided a space to introduce ideas about the nature of environmental racism and the role of neglectful public policy. They served as a meeting ground for our faculty to bring classes, speakers and performers and for visitors to come and enter into dialogues about the meaning of the fiftieth anniversary of the Watts Rebellion. Likewise, students and faculty who had not been to nearby Watts or had not been there for a long time found a space at WLCAC that was welcoming and provided opportunities for further collaboration.

Entering the Picture: Performing Photographs

In many ways, the Watts Rebellion 50th Anniversary laid the groundwork and even produced a hunger for more ways to build collaborations between the arts and the humanistic social sciences. The Annual Labor, Social and Environmental Justice Fair provided a natural space in which to develop the use of photographic practices to build embodied knowledge.

The fair grew out of a student’s observation in 2008 that although Labor Studies had been a unique major at CSUDH since the early 1980s, it had a low profile. The student suggested that we invite unions to campus so that students would learn about the labor movement and the major and the unions would learn more about the students we serve. The organizing of the fair became the focus of a new Labor and Social Justice Club and the culminating project of a capstone Labor Studies course whose students, guided by faculty, raise the funds (from unions and labor-affiliated groups as well as individuals and campus organizations), invite all the participants, determine the theme, organize workshops, design t-shirts, conduct the publicity, order food, recruit student volunteers, invite hundreds of high school and community college students to attend and do all the behind-the-scenes work to make the fair possible. 2009 was the first year of our festive fair; it was attended by hundreds of people and became an annual event.

Over the years, the fair has incorporated many components, including music and art-making, and it has established connections with various departments to build the organizing base and the program. The fair is primarily hosted in front of the Student Union with some workshops held inside, so that the outside walkway becomes a space in which thirty to fifty union and community and environmental groups table and provide information and resources. The art-making booths are the most popular booths. Students and attendees stand in long lines to wait for silk-screeners or airbrush designers and volunteers to help them create social justice-themed t-shirts and environmentally friendly necklaces; another year students created an air-brushed graffiti mural.

We pondered how to integrate further the arts and labor and community participants. Many in our community are interested in social change and intrigued by the tablers who come to the fair, but most are not experienced in asking questions about what the organizations do and how the groups’ work would be relevant to their lives. Unions in particular have been under attack for decades, and even members do not know that much about them. Similarly, while many of the organizations regularly table at public events, they do not necessarily know how to engage with our students. We wondered whether there could there be a way to make deeper connections between the various parts of the fair through art-making.

Price and Bury met with gallery director Zimmerer, instructional support Mossiah and students Meza and Gonzalez in the Art and Design Department for a brainstorming session. The ideas were exciting and innovative and were based on the concept that interactive participatory projects that had a social justice theme would promote a connection between the students and the organizations that came to table. Three main art-making activities were agreed on: the tableau vivant, the half-portraits, and striking a pose. Once these were selected, we worked with the students of the Labor and Social Justice Club on the details of how to put them into practice during the 2017 fair.

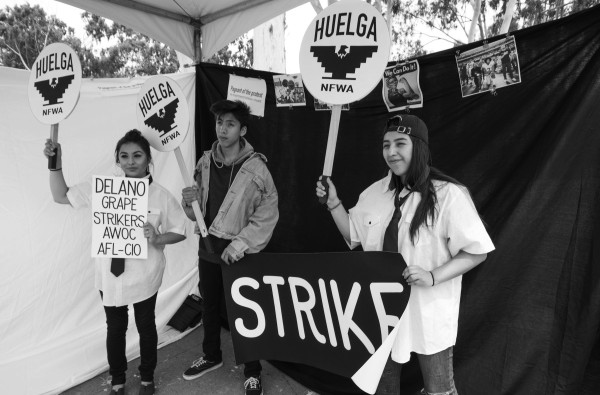

The first activity, the tableau vivant, was a re-enactment of an iconic photo of struggle that we called Pageant of the Protesters, after the Pageant of the Masters, a popular simulation of fine-art paintings held in Laguna Beach every year. Our committee presented several images that would appeal to many people, and students voted to use the 1965 Delano grape strike, the 1961 Women’s Strike for Peace, and Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling protest during the playing of the national anthem in 2016. The second art-making activity was “Strike a Pose,” in which students took the pose from the iconic Rosie the Riveter poster “We Can Do It!” Design student David Meza worked on recreating the different signs from the Delano strike and the Women’s Strike for Peace. Props such as sunglasses, shirts, ties, and bandanas were also purchased. The three photos were printed out for the participants to select from and information about the photos was posted next to them.

The third activity we named “See My Other Half.” Pictures of activists were printed that showed half of their faces on a vertical axis, and participants would hold up the portrait to their own face and take their picture. Design student Meza resized the portraits to approximate the proportion of a real human head. Once again student organizers voted on a group of activists to feature that included Opal Tometi, Dolores Huerta, Angela Davis, Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, Rigoberta Menchu, Gloria Steinem, Cesar Chavez, Michael Moore, Philip Vera Cruz, Huey Newton, Muhammad Ali, Bobby Seale, Jackie Robinson, and Martin Luther King.

During the fair, an open-air photographic studio was created with props and half-portraits on display on tables. Numerous people were present at all times helping with the props and the photos. Approximately twenty reenactments, thirty half-portraits and many Rosies were photographed that day and posted on social media.

Identification and Transformation of the Embodied Image

The reaction of the participants was overwhelmingly positive; initial participants invited their friends to participate in these different activities. High school students from the same class would organize themselves into one or another of the reenactments, which was the only collective photographic activity. Others would look on, take photos, and then either take their turn with the same iconic photo or choose another, grab a picket sign or prop and take a pose, regardless of gender or race. In a poignant moment, one of the Labor Studies organizers who had invited her sister and brother to attend the fair reenacted the Delano grape strike. She explained that they were performing the image in honor of their parents, who had participated in the original strike.

We noticed several interesting patterns. When one thinks of reenactment, the goal is often to get the details as close to the original as possible. But students did not feel restricted by the image. While some carefully arranged themselves like the original image, others were not interested only in “copying” the pose but in embellishing it in order to bring their own identity and history into the experience.

For example, a group of women students assumed the original poses of the marchers in the 1961 Women’s Strike for Peace image and then spontaneously decided to take another photo with their backs facing the photographer to showcase their current activist shirts, several of which bore pro-choice slogans. As there had been a controversy over whether to include an anti-abortion group in the fair, many of the women decided to proclaim women’s reproductive rights visually and wanted to have that documented, while others were showing their Black Lives Matter and Free Education affinities. In a similar fashion, a student decided to wear the Rosie the Riveter bandana to reflect her indigenous heritage, while another student reversed the pose to share her tattoo of the Ecuadorian flag on her other bicep.

Fig. 5. Alexis Sanchez and her siblings reenact the Delano grape strike. (Photograph by Karen Mossiah, 2017, Price’s personal collection.)

The half-portrait of activists, “See My Other Half,” gave our participants the possibility of transforming their identities, a practice merging the selfie and celebrity craze so dominant in the lives of our students. Yet, it was not only students who participated in this and the other activities; faculty and some of our visiting tablers got into the spirit as well. For the Design faculty, being involved in this day-long event meant interacting with strangers to help them select their half-portrait or iconic photos, assisting them in dressing up, and striking up spontaneous conversations about the events with the activists, asking them which surrounding high school they were from or which major they were pursuing. It was an atypical experience. It was visceral and experiential for us as well.

Fig. 6. Larae Staten, one of the fair organizers, strikes a Rosie pose. (Photo by Karen Mossiah, 2017, Price’s Personal Collection.)

Reflecting on the implementation of the project has been thought-provoking. The success of creating visual narratives as socially engaged art means that a number of us are continuing to use collaborative field trips, student photography and poster creation as ways of building reciprocal relationships with surrounding communities. For the fair, the iconic photos have many possible variations and could develop into a more extensive experience. Moving forward, we are considering creating a village of reenactments of social movements that would be modelled on the interactive exhibit by Doctors Without Borders addressing the international refugee crisis.11 Creating a space for the making of visual narratives is a profound method for raising political awareness through the production, interpretation and performance of images and text.

Fig. 7. Faculty member Marisela Chavez and her “other half,” Dolores Huerta. (Photo by Ellie Zenhari, 2017, Price’s Personal Collection.)

Fig. 8. Paul Wooten and his “other half,” Patrisse Cullors. (Photo by Ellie Zenhari, 2017, Price’s Personal Collection.)

Notes

1 Helguera, Education for Socially Engaged Art.

2 Ibid., 8.

3 Shuman, “Entitlement and Empathy in Personal Narrative,” 148-55.

4 Grimshaw and Ravetz, Visualizing Anthropology; Sutherland and Bryant, “Autobiographical Memory in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder,” 2915-23.

5 Degarrod, “Making the Unfamiliar Personal,” 405.

6 Boal, Games for Actors and Non-Actors.

7 Biesta, “Becoming Public,” 683-97.

8 “History Timeline,” California State Unviersity, Dominguez Hills.

9 Helguera, Education, 8.

10 Price, “Mapping Connections.”

11 “What is Forced From Home?”, Doctors Without Borders.

Bibliography

Biesta, Gert. “Becoming Public: Public Pedagogy, Citizenship and the Public Sphere.” Social & Cultural Geography 13, no. 7 (2012): 683-97.

Boal, Augusto. Games for Actors and Non-Actors. Translated by Adrian Jackson. New York: Routledge, 2002.

California State University, Dominguez Hills. “History Timeline.” History, Missions & Vision. Accessed March 14, 2017. https://www.csudh.edu/about/history-mission-vision/text-version.

Degarrod, Lydia N. “Making the Unfamiliar Personal: Arts-Based Ethnographies as Public-Engaged Ethnographies.” Qualitative Research 13, no. 4 (2013): 402-13.

Doctors Without Borders. “What is Forced From Home?” Forced From Home. Accessed April 15, 2018. http://www.forcedfromhome.com/about/.

Grimshaw, Anna, and Amanda Ravetz, eds. Visualizing Anthropology. Porland, OR: Intellect Books, 2005.

Helguera, Pablo. Education for Socially Engaged Art: A Materials and Techniques Handbook. New York: Jorge Pinto Books, 2011.

Price, Vivian. “Mapping Connections.” YouTube video, 17:00. Posted July 29, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H8uj1qWaY6U.

Shuman, Amy. “Entitlement and Empathy in Personal Narrative.” Narrative Inquiry 16, no. 1 (2006): 148-55.

Sutherland, Kylie, and Richard A. Bryant. “Autobiographical Memory in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Before and After Treatment.” Behaviour Research and Therapy 45, no. 12 (2007): 2915-23.