Swati Chattpadhyay

Colonial Sovereignty and Territorial Affect

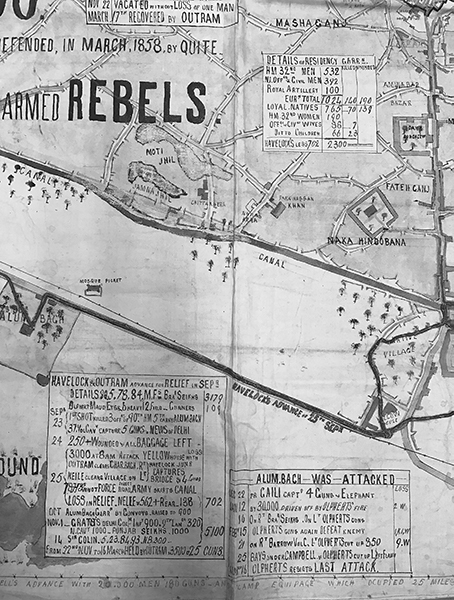

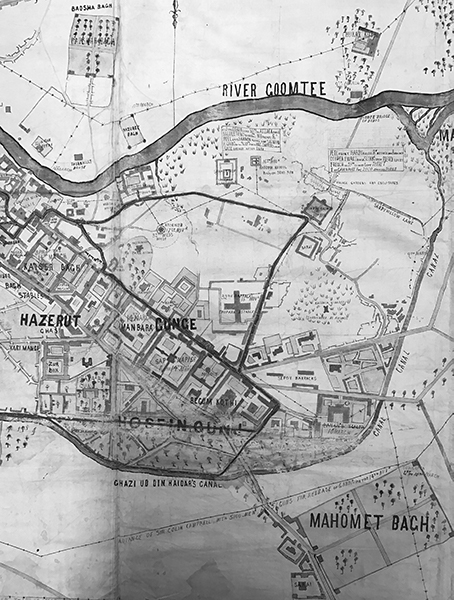

Among the documents of the 1857 Sepoy Revolt in the collection of the British Library is a cloth map showing British military positions in and around Lucknow, the capital of the princely state of Awadh in northern India. Created c 1890, the map provides a narrative of three separate advances to relieve the besieged British garrison at the Lucknow Residency. It highlights General Havelock’s September 1857 march by marking the line of advance with a gold zari cord (Fig. 1).1 The line of advance halts at the boundaries of the native city and skirts around its perimeter through the suburbs to reach the Residency. That golden path, in relief on the map’s flat fabric surface, much tarnished in the hundred odd years since its creation, remains an invitation to viewers to touch that path of attack and feel the campaign. The use of zari, known for its use as gold decoration in clothing and furnishing in India, suggests an exceptional investment in producing this commemorative map three decades after the event.

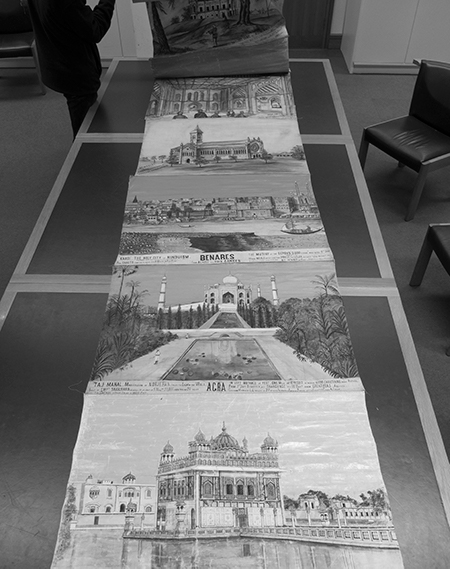

The creators of the map, the Reverend Thomas Moore and his wife Dorothy, produced another “mutiny map” of Cawnpore (Kanpur)2 as well as a set of twenty-six paintings of mutiny sites, which they organized in the form of a narrative scroll, 53 feet, 1-inch long (Fig. 2).3 The maps and the scroll were intended to be viewed in relation to each other and invite a close handling of the visual material—touching and unrolling in sections for effective viewing—as the size of these documents requires space and attention. The documents also evince a territorial aesthetic that demands an embodied reading of successful occupation, victory, loss, vengeance, and sovereignty. The landscape itself appears as a series of military occupations that are at the same time deeply aestheticized and emotive. To borrow Kathleen Stewart’s words, here “ontologies jump into affecting forms to become fields, catchment areas, trajectories of action or pools of sensory impact.”4

Fig 1. Detail of “Plan of The Three Advances on Lucknow” (Thomas and Dorothy Moore, 1890, British Library). ©British Library Board.

Fig. 2. Mutiny Scroll (Thomas and Dorothy Moore, 1890, British Library [Add Ms 37153]) ©British Library Board.

I see in the affective gesture of these visual documents a much-overlooked dimension of sovereignty—that the performance of sovereignty requires not only territorial occupation but an affective investment in the occupied land. What we find in the map produced by two ordinary functionaries of empire is an assumption of sovereign claims and a labored effort at articulation and representation that behooves us to rethink the basis and exercise of sovereignty.

***

Theorists of sovereignty have primarily focused on the state and the mythical origins of sovereign power by virtue of which the state arrogates to itself the right to violence. Much less attention has been accorded to the innumerable agents through whom sovereignty is produced and materialized. For Foucault the move toward understanding such capillary networks of power meant moving away from the “false paternities” of Hobbes and Machiavelli,5 in particular the statist-Hobbesian model of sovereignty as the Leviathan.6 Foucault’s historical argument was premised on the claim that the model of “disciplinary power” that emerged in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe, with its peculiar procedures, instruments, and equipment, was “radically heterogeneous” and incompatible with the idea of sovereignty.7 So why did theories of sovereignty not only survive industrial capitalism, but flourish? Suggesting that the reasons resided in the democratization of sovereignty and the emergent idea of right that could be used against the state, he posited the functioning of power between two poles: sovereign rights and a “polymorphous mechanism” of regulations and discipline.8

In the end, for Foucault and other theorists, juridical sovereignty is absolute power. Sovereignty divided is no sovereignty at all, Hobbes would say; the sovereign decides on the exception, according to Schmitt. What if we relax the assumption that sovereignty is absolute power? This is not to suggest we assume a model of degrees-of-sovereignty: to say some states are more or less sovereign risks positing false comparisons. Rather, what if, following Sudipta Sen and Lauren Benton, we learn to read the formulation and exercise of sovereignty as contingent, layered, and anomalous? This might require our investment in the idea that sovereignty, like disciplinary power, works through capillaries.

There are compelling reasons to relax the assumption of sovereignty as absolute power, particularly in view of what we might then learn about the territorial imperatives of sovereignty. An absolute-statist view of sovereignty assumes a static, bounded space as a precondition for its exercise.9 As Wendy Brown points out, theorists, while acknowledging land appropriation as the precondition of sovereignty, have long identified sovereignty with “settled jurisdiction” rather than “with settling it.”10 Not surprisingly, those scholars who have attended to the dynamics of sovereign state formation, such as Sen and Benton, study colonial sovereignty, in which settling distant land, rather than a settled land, is the object of sovereign power.11 The historical process of settling was necessarily uneven, and as Benton notes, even “in the most paradigmatic of cases,” the spaces of empire had “porous boundaries,” were “politically fragmented” and “legally differentiated.”12 Territorial sovereignty was not only contested through rebellion at various points of time, but juridical sovereignty and its law-making and law-maintaining functions had to negotiate the heterogeneous topography of territorial possessions and thus in a fundamental sense remained unsettled.

The precariousness of European territorial power in the colonies meant that sovereignty teetered on the verge of outright domination.13 In moments of crisis, this domination took the form of power as terror exercised by state functionaries, even when not fully authorized by the colonial state. For example, terrorizing the native population as a way to create a “moral effect” was resorted to by British officers in India not only during the Sepoy Revolt but many times after, into the twentieth century.14 Terror was a chosen strategy of demonstrating state power in moments of crisis, in the form of brutal executions, burning of villages, destruction of property, and humiliating punishments meted out to civilians. Intended to “punish and awe,” the purpose of the systematic burning of villages and towns by British orders during the Sepoy Revolt was less to avenge the loss of British lives than to exact retribution for having felt the “degradation of fearing those whom we had taught to fear us.”15 To put it another way, terror exposed the crisis—the perpetual crisis of colonial sovereignty. This perpetual crisis, however, was not simply indexed in terror but manifested in a range of affective investments in territory that followed violent ruptures.

That terror and fear are the only affects we have come to identify with sovereignty has something to do with the reading of Hobbes and the figure of Leviathan in whose terrifying volition Hobbes grounded the absolute power of the sovereign. But Hobbes’s sovereign is faced with myriad “passions” that do not disappear with the assumption of sovereignty; the sovereign must subdue, organize, channel these passions to bring the warring tribes to the table to form the commonwealth, to secure consent.16 In the end, Hobbes inserted the possibility of resistance, when the sovereign fails to meet his obligation, in such unextinguished passions—the font of natural right. This could apply not only to colonized populations but also to colonial sovereign-subjects. In other words, one could as well say that British functionaries of empire in India and elsewhere, when they resorted to violence without the explicit sanction of the state, did so because they felt that the state (read political leadership at that moment) was incapable of exercising sovereignty: it was thus their “natural right” as sovereign subjects to exercise the power that justly belongs to the sovereign.17

I propose that to recognize these marginalized yet readily visible possibilities, we set the model of sovereignty afloat, if you will, in the current of historical experience, with its sandbars, whorls, and eddies, to see what else accretes to the idea and ideal of sovereignty as absolute power. The process of settling the land and the violent confrontation with the people whose land is being appropriated and occupied generate a range of power-effects and corresponding affects that exceed the singularity of fear instituted by the sovereign. There is no reason to presume such accretions necessarily weaken state sovereignty, even if they transform it. This is to say, I wish to make an argument not about the weakness or strength of sovereignty but about its governing conditions.

Let me be clear on this point. There is no denying that terror is structural to sovereignty. However, relaxing the idea of absolute sovereignty enables us to see the unextinguished but curbed passions of subjects that generate the checkered topography of sovereignty. Building on the work of Sen and Benton, who have chipped away at the idea of absolute sovereignty, following a track different from that of Foucault, I have two inter-related propositions:

- Sovereignty is a process. It must be continually performed—reproduced, re-worked, re-cited.

- Reproduction of sovereignty invites an affective investment in territory. By territory I mean land that is defended, occupied, and treated as an instrument of power. Territorial affect rises to the surface when sovereignty faces a crisis.

***

In May 1857, Indian soldiers (“sepoys”) of the East India Company’s army stationed in Meerut mutinied. Their initial success emboldened them to march to Delhi and re-assert the sovereignty of the pensioned octogenarian Mughal emperor Bahahdur Shah II. As the mutiny spread, it acquired the form of a popular revolt across much of northern and central India: the rebel soldiers were joined by landholders, disaffected leaders of princely states, peasants and townsmen. By the time the revolt was declared subdued by the British Government, the nominal sovereignty of the Mughal emperor had been extinguished, ushering in the age of the Raj. The British monarch’s Proclamation of November 1858 transferred the governance of British Indian territories from the East India Company to the British crown, producing a new era of declarations of British sovereignty over Indian lands and populations.

The Queen’s Proclamation initiated a rearticulation of the relation between Sovereign and Subject that became a reference point for the remainder of British rule in India.18 It is worth looking at the Proclamation at some length to decipher the contours of community, territory, law and subjecthood drafted in the configuration of a new sovereignty that on essential points differed from the kind of national sovereignty practiced in Britain:19

…We have resolved…, to take upon Ourselves the said Government; and We hereby call upon all Our Subjects within the said Territories to be faithful, and to bear true Allegiance to Us, Our Heirs, and Successors, and to submit themselves to the authority of those whom We may hereafter, from time to time, see fit to appoint to administer the Government of Our said Territories, in Our name and on Our behalf….20

The communal-possessive repetition of Us/Our/Ourselves constructed the authoritative ground from which sovereign power emanated. The Proclamation’s calling upon “Our Subjects” “to submit themselves” marked Indians as the addressee. Within this body of Indian “Subjects,” the nominal sovereignty of Native Princes had to be accepted and at the same time circumscribed:

We hereby announce to the Native Princes of India that all Treaties and Engagements with them by or under the authority of the Honorable East Indian Company are by Us accepted, and will be scrupulously maintained; and We look for the like observance on their part….

…We shall respect the Rights, Dignity, and Honour of Native Princes as Our own; and We desire that they, as well as Our own subjects, should enjoy that Prosperity and that social Advancement which can only be secured by internal Peace and good Government.21

Not permitted to define their own foreign policy, the Native Princes were only responsible for “internal” governance under the watchful eye of a British resident, and the declared allegiance/subjection of princely states to the British sovereign made it possible to place the well-being of Native Princes on a par with that of “Our own Subjects” (those who were under direct rule). Here we see the language of sovereignty slipping into an instance of what Benton might describe as “quasi sovereignty.”22 But the heterogeneous topography of sovereignty needed to be organized and clarified if the paramountcy of the British sovereign was to have the force of law:23

We hold Ourselves bound to the Natives of Our Indian Territories by the same obligations of Duty which bind Us to all Our Subjects….

We know, and respect, the feelings of attachment with which the Natives of India regard the Lands inherited by them from their Ancestors; and we desire to protect them in all Rights connected herewith, subject to the equitable demands of the State.24

If obligations of Duty bound the sovereign to all her subjects, irrespective of who they were or whether they were in India or Britain, the Proclamation elided the fact that, unlike in England, no consent was sought from the subjects in India. Consent was supplanted first by fear and then by dutiful compliance and gratitude for having life spared. After assuring Indian subjects of benevolent governance, religious freedom, and equality under the law, irrespective of “Race or Creed,” the Proclamation went on to assert superior force of arms as the rationale and guarantee of sovereignty:

Our Power has been shewn by the Suppression of that Rebellion in the field; We desire to shew Our Mercy, by pardoning the Offenses of those who have been thus misled, but who desire to return to the path of Duty.25

There were exceptions, however:

Our clemency will be extended to all Offenders, save and except those who have been, or shall be, convicted of having directly taken part in the Murder of British Subjects. With regard to such, the Demands of Justice forbid the exercise of mercy.26

The unconditional validation of the life of British Subjects over that of natives was the key to clarifying the landscape of sovereignty. After all, Indians were not going to be executed for killing other Indian civilians or Indian soldiers who fought for the British army. The constitution of British Subjects as an already sovereign community deserving of special legal and ethical considerations sat askew with the desire to constitute a new imperial community of subjects irrespective of “Race or Creed.” The Proclamation differentiated between Citizen and Subject, between the community of conquerors and that of the conquered, between the Duty-bound, pardon-offering British sovereign and a native people (“p” in lower case), and between Territory and Land. The natives, it was recognized, had “feelings of attachment” to the “Land inherited by them from their ancestors.”27 The Land converted into Territory enabled its occupation by the conquerors. The conqueror-legislator would administer in exchange of “Allegiance” and “Gratitude” from the natives:

It is Our earnest Desire to stimulate the peaceful Industry of India, to promote Works of Public utility and Improvement, and to administer its Government for the benefit of all Our Subjects resident therein. In their Prosperity will be our Strength; in their Contentment Our Security and in their Gratitude Our best Reward.28

By the end of the Proclamation, sovereign will has produced a description of a sovereign community through the alignment of a set of relations—Us/Our/Ourselves/British Subjects—marking the difference between the new sovereign and they/them/Native Princes/natives. By producing a hierarchical ordering of communities within the Raj, with the British community at its apex, the Proclamation demanded of all native communities, including those of the Native Princes, feelings of subjecthood-as-subjection in the service of the new sovereign. The fear instilled in the native subject and gratitude for mercy were explicitly articulated, because neither was assured in November 1858, as rebellion persisted in the countryside. The Proclamation was anticipatory; a tool for pacification, it preceded the British ability to exercise sovereignty.

By British law, royal proclamations had legislative power in the newly conquered colonies and were unidirectional tools of exercising control that required no other legislative assent. For example, Lord Canning’s March 1858 Proclamation, issued in anticipation of the fall of Lucknow (on which the Queen’s November Proclamation was based), was, as John Kaye correctly identified, a “sentence, a warning and a threat.”29 The Queen’s Proclamation affirmed Lord Canning’s Proclamation and in one bold stroke sought to legitimize the usurpation of previous claims to sovereignty, namely, the nominal sovereignty of the Mughal emperor. No mention was made of the Mughal emperor in the Proclamation, let alone Bahadur Shah II, as a sovereign. The sentence passed on the Mughal emperor was for “treason,” as if he were already a subject of the British Crown.30

Marking the fiftieth anniversary of the 1858 Proclamation the next British monarch, Edward VII, issued a 1908 Proclamation that reasserted the terms of sovereignty articulated in the former. In addressing “my Indian subjects” directly in terms of “you/your/yours,” he dispensed with the seeming ambiguities that troubled the lines among overlapping communities, between the “Us-them” of the 1858 Proclamation, to stage a clear dichotomy between we/our/British ruler and you/your/Indian subjects:

The incorporation of many strangely diversified communities, and of some three hundred millions of the human race, under British guidance and control has proceeded steadfastly and without pause. We survey

our labours of the past half century with clear gaze and good conscience…

…For a longer period than was ever known in your land before, you have escaped the dire calamities of War within your borders…

The schemes that have been diligently framed and executed for promoting your material convenience and advance – schemes unsurpassed in their magnitude and their boldness….31

As with the 1858 Proclamation, Edward VII felt obliged to remind his Indian subjects of his “paramount duty to repress with a stern arm guilty conspiracies that have no just cause and no serious aim.”32

The 1858 Proclamation, in calling out the superiority of British claims, gave permission to British Subjects to acquire the mantle of imperial-sovereign subjects, and to redraw “race” as the defining logic of colonial sovereignty. And despite this naturalization of sovereignty over conquered territory, or perhaps because of it, a series of measures was taken to make this new era of colonial sovereignty a palpable territorial reality.

Some of the immediate measures included systematic state-sanctioned looting and destruction of palaces, towns and villages by British soldiers.33 When Delhi was captured by British troops in September 1857, soldiers were given permission to loot the Mughal capital on their own for three days. Then under the supervision of military officers acting as Prize Agents, the city was systematically looted for three months: looting asserted the rights of sovereignty.34 Times correspondent William Russell, reporting the revolt from British camps, wrote of being astounded by the expansiveness and ferocity of wanton destruction and summary executions.35 A staunch supporter of the British cause to suppress the revolt, Russell felt compelled to write, “I think we permit things to be done in India, which we would not permit to be done in Europe, or could hope to effect without public reprobation; and that our Christian character in Europe, our Christian zeal in Exeter Hall, will not atone for usurpation and annexation in Hindostan, or for violence and fraud in the Upper Provinces of India.”36

An extensive network of newly built military cantonments—with some, like Lucknow’s, being substantially larger than the city to which they were attached—produced a clearly hierarchical relation between cantonments, civil lines, and the native city and facilitated a close braiding of civil and military administrations. The growth of cantonments was accompanied by a reorganization of the army of the Raj. The proportion of Indian soldiers in the army was reduced, and new recruits were drawn from regions that had remained loyal. Indian artillery was disbanded, as cannons in Indian hands had come to be seen as a terrifying prospect.37

After the revolt, the belligerent cities of Delhi, Lucknow, and Kanpur were drastically reshaped to secure their military futures.38 The continued occupation of royal palaces and public buildings for use as barracks, offices, and clubs, some for two decades and others until the end of British rule, repositioned the loci of power in these cities. Much of this reorganization involved building parks, gardens, and tree-lines avenues on confiscated lands, producing a landscape aesthetic that linked the space of the cantonments, civil lines, and the open countryside as a series of recreational spaces for horse riding, picnics, and hunts.39 This landscape incorporated mutiny sites and a number of newly built “mutiny memorials.” One of the most revered sites, the Kanpur Memorial Well, was located in a spacious garden built for that purpose and bounded by a marble gated enclosure within which Indians were not permitted to enter.40 In the subsequent decades these mutiny sites became the constituent elements of mutiny tours of northern India that Britons were expected to visit to recall the trials and victories of a Christian British community. There was little room for the growing number of Indian Christians in this feeling of community.41

The mutiny memorials helped rehearse British sovereignty as a shared ethos among the colonizers, while the moment of sovereign claim was repeated every decade or two in the staging of imperial durbars that became occasions to reassert sovereignty in a style that both recalled and surpassed the grandeur of the Mughals.42 Twenty years after the revolt, the 1877 imperial durbar in Delhi, at which Queen Victoria was declared Empress of India, marked the apogee in the performance of colonial sovereignty.43

Not all marks of sovereignty, however, were produced by the state. In the performance of colonial sovereignty, the state was enabled by a plethora of representations produced by non-state functionaries and those in the lower rungs of the colonial state machinery, such as the Moores with whose map and scroll I began this article. Colonial sovereignty was assumed, enhanced, and expressed by ordinary Britons who exercised little power as state functionaries, beyond that which they assumed as a matter of white racial superiority, constructed anew after the revolt, and backed by scientific racism, legal instruments, and liberal political thought.44 These state and non-state functionaries did not all speak in one voice. As in Russell’s war journal, fissures, doubts, and silences run through these representations: anxiety, despondence, and guilt are woven through the affective discourse of glory, victory, and pride. It is thus instructive to examine the representations produced outside the aegis of the state, often in private capacity, to understand how colonial sovereignty was assumed, performed, and refracted.

***

When the revolt began, Thomas Moore was in Calcutta, hoping for an appointment as chaplain with the East India Company. To his alarm, his first posting in September 1857 was Kanpur, where a few months ago Europeans had been slaughtered after a decisive loss suffered by the British troops under General Wheeler. His wife, Dorothy, and their infant son were permitted to join him in 1858, and during the rest of his career with the army until his retirement in 1879, the couple acquired first-hand experience of several mutiny sites besides Kanpur: in Lucknow, Benares, and Jhansi.45 The maps and scroll they produced located their experience of these places on the battle sites, post-facto.

Even before the revolt was over, Thomas had started collecting objects and materials from battle and massacre sites in anticipation of their future importance as commemorative objects and documents. This included “several pieces of the dresses” from the Beebighar, where British women and children were killed, and pieces from the back door through which their bodies were dragged out to be thrown into a well.46 He also produced a few sketches and plans of these sites. And yet, most of the twenty-six panels that constitute the scroll are not based on Thomas’s sketches but on the photographs, paintings, and drawings produced during and after the revolt by their contemporaries. There is thus in the content of the representations a sense of emulation and re-citation producing a narrative of collective enterprise—an attempt to represent the trials and tribulations of a Christian community. This was no doubt a product of Thomas’s vocation as a chaplain, but it is the same Christian sensibility that was enlisted to erase imprints of revenge from the images.

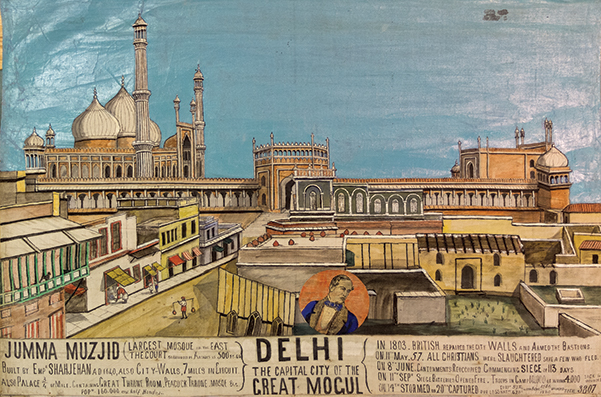

Fourteen depictions of Lucknow, flanked by eight views of Kanpur, constitute the central part of the mutiny scroll, with views of the Jumma Masjid in Delhi, Benaras from across the river, the Taj Mahal at Agra and the Golden Temple at Amritsar serving as bookends. The latter two had no substantive connection with the revolt, but as a catalog of tourist destinations, the sites depicted in the scroll constituted the mutiny tour of northern India that would have been familiar to European viewers.

Fig. 3. “Delhi, The Capital of the Great Mogul,” a panel from the Mutiny Scroll (Thomas and Dorothy Moore, 1890, British Library [Add Ms 37153].) ©British Library Board.

The scroll panels are not organized in a chronological sequence. The first panel, labeled “Delhi: Capital City of the Great Mogul,” shows the Jumma Musjid, or congregational mosque, to mark the assumption of sovereignty (Fig. 3). The mosque, rather than the Red Fort in Delhi, stands in for the vanquished sovereignty of the Mughal Empire, giving the conflict a primarily religious reading. A paper portrait medallion of Governor General turned Viceroy Lord Canning, pasted in the center, above the panel title, represents the victor/new sovereign representative. The texts on either side of the medallion convey the panel’s message and set the tone for the rest of the scroll. On the left we have a few details of the city and its monuments that would have been of interest to a British audience, and on the right an abridged history of British ascendancy and takeover of Delhi. The narrative thus reaches back to 1803 (when the Mughal emperor sought the East India Company’s military assistance in warding off the Maratha invasion and effectively became a pensioner of the Company), and concludes with the British storming and capturing of Delhi on 20th September 1857. Words inscribed in all capital letters—BRITISH, WALLS, CHRISTIAN, SLAUGHTERED, SIEGE, STORMED, CAPTURED—shout out a self-evident justificatory logic of cause and effect. These words, scattered about in the remaining panels and in the maps of Lucknow and Kanpur, become the grounds for articulating a new sovereign sensibility.

The maps and scroll complement each other and have a shared iconography replete with texts. Placed in well-defined boxes to distinguish them from the topographic rendering, the texts cite military details. Following the practice of military maps of the time, the strength of the army in terms of personnel and armament is detailed, and small plans depicting entrenchments and armed positions of the belligerents populate the scroll paintings. However, what might at first glance appear as a tabulation of military strength is overlaid by the roles that individuals played and the impact of their actions. The military details are transformed into an animated narrative of events, as the viewer is asked to enter the landscape and become familiar with the specific locations—gardens, walls, buildings, canal, river—that were targeted, defended, and secured and where lives were lost.

The Lucknow map is layered with information about three different attempts to reach the Residency next to the river. The paths of advance, delineated so as to be visually distinct, organize the topography and allow the viewer entry into the zone of conflict. On the left of the map, the narrative of advance, defeat, and ultimate victory begins with a benchmark that defines the enormous adversity faced by British troops:

THE CITY OF LUCKNOW WAS 20 MILES IN CIRCUMFERENCE IN 1857-8, HAD A POPULATION OF 500,000 AND WAS OCCUPED AND DEFENDED IN MARCH 1858 BY QUITE 100,000 WELL ARMED REBELS.

As in the scroll, the capitalized words in bold font provide key information. Military details in rectangular frames pepper the spaces next to the lines of advance. Following these lines, the viewer moves with the army, so to speak, to halt at the sites of military significance. Sir Colin Campbell’s November 1858 march along the outskirts of the city of Lucknow across the Dilkhusa grounds and through Martinere Park touches on the important positions that were gained/lost, with their dates indicated next to the site: “STORMED 9th MARCH,” “TAKEN 15th NOV.” Annotations in the form of framed texts are “planted” on building site plans like flags. Marks of territorial occupation, such flags contain episodes of conflict as in telegraphic messages that convey the progress of a campaign:

At 3 PM COLIN LEAD 93rd to ATTACK FAILS

MIDDLETONS GUNS LT N. BRUCKET RT

… 93rd FINDS HOLE SAPPERS OPEN

GATE OPENED AFTER DARK

Or the following:

PEEL FRONT HARDY KILLED Ar ATTACK . . .

COOPER EWART RACE SEIKHS FOR BREACH…

2 OF CAWNPORE REGT 2000 COUNTED BURIED. (Fig. 4)

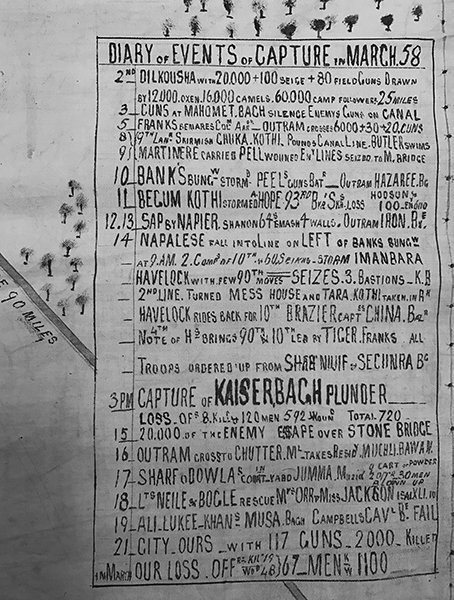

The pattern of these flagged texts is replicated in the “Diary of Events of Capture on March 1858” that emphasizes the sublimity of the endeavor in terms of the strength of the army: 20,000 men, 80 field guns, 12,000 oxen, 16,000 camels, and 60,000 camp followers (Fig. 5). Each day’s key events from March 2nd to March 21st are then spelled out as a series of actions and outcomes—“STORMED,” “RESCUE,” “SIEZES,” “PLUNDER,” “CITY OUR”—to produce an active encounter with the topography of conflict.

These texts bring together bits of information and are layered, collage-like, to give a certain “thickness” to the map that complements the felicitous touch of the zari cord marking Havelock’s advance. Together they build a landscape, by stirring the imagination, and produce a territorial affect akin to Russell’s reaction on seeing Satchaura Ghat or “Massacre Ghat” in Kanpur:

My imagination completed the details of the dreadful picture: the waters flowed red with blood—the air was filled with the smoke of musketry—the thick white puffs, through which rustle flights of deadly grape, roll from the trees—the despairing screams of women rise above the hellish tumult of the murderers and their victims—streams of black smoke rise from the burning boats! I turned and left the spot with every vein boiling, and it was long ere I could still the beatings of my heart.47

Fig. 4. Detail of the “Plan of The Three Advances on Lucknow” (Thomas and Dorothy Moore, 1890, British Library). ©British Library Board.

Russell’s “picture,” by the sheer dint of imagination, exceeds the visual to generate “affecting forms.”48 The “thick white puffs” from musketry fire and the “streams” of smoke rising from the burning boats carrying British families become visible again, and the river turns red with British blood amid the noise of murder and despair. These forms transport Russell to the moment of tumult and overwhelm the veteran war reporter. Short of participating in a mutiny tour to see with one’s own eyes the sites where British lives were lost, as Russell and the Moores did, the texts on the map simulate the emotive experience of “being there.” Designed to encourage a pictorial imagination to make visible that which cannot be seen so many years after the event, the texts in the maps enable viewers to “complete the picture” and thus activate the affect of imperial sovereignty.

Fig. 5. Detail of the “Plan of The Three Advances on Lucknow” (Thomas and Dorothy Moore, 1890, British Library). ©British Library Board.

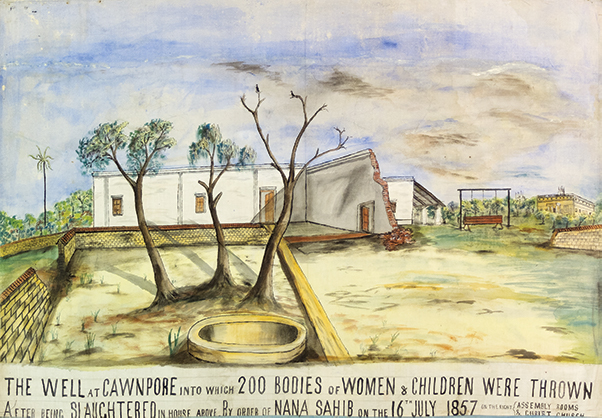

While the texts bestow on both the scroll and maps the triumph and tragedy of conflict, the representations of buildings in the scroll are remarkably shorn of violence. The images represent the buildings and sites presumably after the revolt, not during it. And yet, the placid atmosphere of the Dilkhusa Palace, Colin Campbell’s headquarters during the relief of Lucknow, is presented without any marks of shell-damage. Only the terse text explains its import. The image of the Residency building shows cannon marks but is a far cry from the photographs of the heavily bombarded Residency that Thomas had in his journal. “Well at Cawnpore,” which depicts the well into which the bodies of women and children were thrown, shows no evidence of blood or dead bodies (Fig. 6). The smallness of the well-head even works counter to the affect intended in the title of the image. The utter ordinariness of the well is rendered significant by framing it with the partially demolished Bibighar behind it and the Assembly Building and Christ Church in the distance. The gallows in the middle ground attests to the punishment meted out to the rebels within sight of the two spaces of slaughter. The vengeful texts on the walls of Bibighar written by British soldiers do not appear in the paintings, nor do any signs of torture by British soldiers mar the post-revolt landscape.49 Without textual reference, Satichaura Ghat in the Moores’s rendition is just another ghat, indistinguishable from others.

Fig. 6. “The Well at Cawnpore,” a panel from the Mutiny Scroll (Thomas and Dorothy Moore, 1890, British Library [Add Ms 37153]). ©British Library Board.

Despite their shared iconography, there is a tension between the representational strategies of the scroll and the maps: between the danger of creating scenes too vivid for respectable viewing and the impulse to supplement, through textual explanation, that which is too risky to represent pictorially; between erasure of the violence through which sovereignty was assumed and continual, devout remembrance of that very moment of violence. As the mutiny spaces spill over into the everyday landscape, the post-revolt landscape is settled, given a place within a larger narrative tour of networked spaces that keep alive the representational tensions that uphold sovereignty.

***

Assessing the impact of the Sepoy Revolt on British governance of India, Thomas Metcalf, in his groundbreaking 1964 monograph, argued that the mutiny and rebellion marked a decisive shift in the structure and nature of British rule and in British attitude toward India and Indians. British politicians, civil servants, and military leaders, liberals and conservatives alike, with rare exception, agreed that Britain had acquired and ruled India by military might and that such imperial dominance must be displayed by placing the power and honor of the British official front and center. In the post-revolt decades, Metcalf noted, the British gave up on their earlier, 1830s ideas of reforming Indian society, retreated increasingly into their own community, and limited their administrative responsibilities to the maintenance of law and order and the construction of public works to aid the infrastructure of governance: “Beyond this all was hazy.”50 In this haziness Metcalf discerned an indecision regarding the nature of colonial occupation. He pointed out that The Economist had told the British people in September 1857, at the height of the revolt, that they now had to decide “whether in future India is to be governed as a Colony or a Conquest….” Metcalf concluded: “The decision was never made.”51

From the point of view of The Economist, the idea of India as a Colony would have meant treating India as a “settler colony” and treating Indians, “Hindus and Mahomedans as our fellow citizens,” and India as Conquest would have meant ruling “our Asiatic subjects through strict and generous justice, wisely and beneficently, as their natural and indefeasible superiors by virtue of our higher civilization.”52 If the debate between India as Colony and as Conquest was undecided, it is not because conquest and claims of governing by virtue of conquest were not asserted. In Hobbesian terms, and as clearly articulated in the Queen’s 1858 Proclamation, India was a case of sovereignty by conquest or acquisition and not by consent.53 Hobbes, however, did not admit the idea of a non-settler colony. For him, sovereign subjects could found a colony by occupying distant land that was “vacant” or by exterminating those who lived on it by war. Once such colony was settled, it could remain a province of the sovereign metropole or could constitute a new sovereign commonwealth.54 Either way, there was to be no competing sovereignty, and there was no opposition or debate between colony and conquest.

Contra Hobbes, sovereignty by acquisition on the part of the British colonial state in India came with specific problems of territory, place, and belonging, given the realities of a non-settler colony as well as the expansion and transformation of territorial possessions in the long career of the British empire in India. As a non-settler colony, British colonial sovereignty in India ran into some constitutive contradictions. Indians were defined as subjects not citizens—so there could not be any popular sovereignty. The British were citizens but not settlers in India, and the relation between law-makers and the land was at best a self-professed custodianship.

Territorial sovereignty in India was unsettled in two senses: it arose from the imperatives of a non-settler colony, and it swayed between “settling the land” (by the force of conquest and revenue administration) and a perpetual movement of a minority of Britons between camps and stations to conduct their task of governance. Colonial officials were “posted” temporarily at stations; they went on circuit, and they did inspection tours. Children above the age of seven were sent back “home” to England, as India was seen as climatically and socially unsuitable for raising future rulers of the empire. To be domiciled in India—to be settled—was to become a second-class British citizen. Perpetually traversing, almost fearful that commitment to place would be fatal to the body and the future of empire, Britons in India were taught to see the landscape through a lens of power that was not grounded in a sense of belonging. The haziness that Metcalf discerned was thus not a product of indecision but a constitutive ambivalence of colonial sovereignty.

We get a sense of this ambivalence in the tension of the affective gestures that mark the maps and scroll produced by the Moores. When attachment to land and acquiring a sense of belonging is impossible, or, at best, infelicitous, the desire to mark the land with one’s presence takes on a different urgency. Their depictions of the mutinous landscape demonstrate an effort to anchor the space with episodic events, abbreviated texts, and “copied” images, in a manner that is imaginative and theatrical and at the same time obsessed with citations and details evincing truth claims. As such, they speak to the urgency of creating a landscape of territorial affect.

Notes

1 British Library, Add MS 37152 A.

2 British Library, Add MS 37152 B.

3 British Library, Add MS 37153.

4 Stewart, “Preface,” xv.

5 Foucault, “Society Must be Defended,” 59.

6 Ibid, 34.

7 Ibid, 35-36.

8 Ibid, 37-38.

9 See, for example, in Hobbes’s discussion of commonwealth colonies as sovereignty ensuing after the “colony is settled”; Hobbes, Leviathan, 194.

10 Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty, 59.

11 Sen, Distant Sovereignty; Benton, A Search for Sovereignty; Sen, “Unfinished conquest,” 227-242.

12 Benton, A Search for Sovereignty, 2.

13 Metcalf, The Aftermath of Revolt, 292; Chakrabarty, “‘In the name of politics,’” 3293-301.

14 See the discussion of the Jallianwallahbagh Massacre in Hussain, The Jurisprudence of Emergency.

15 John W. Kaye, History of the Sepoy War, 269.

16 Hobbes, Leviathan, 43-44.

17 On this point, see the discussion in Sreedhar, Hobbes on Resistance, 132-67.

18 “Proclamation, by the Queen in Council.”

19 For more on national-imperial sovereignty in Britain, see Sen, A Distant Sovereignty.

20 “Proclamation, by the Queen in Council,” 1.

21 Ibid.

22 Benton, A Search for Sovereignty, 236-45.

23 The logic of the British is the paramount power in India was used to bring all quasi-sovereign states under the aegis of the British Government. See Benton’s discussion of paramountcy in the case of the princely state of Baroda as “the prerogative of the imperial power to decide where law ended and politics began,” A Search for Sovereignty, 258-60.

24 “Proclamation, by the Queen in Council,” 1.

25 Ibid., 2.

26 Ibid., emphasis added

27 Ibid., 1.

28 Ibid., 2.

29 Kaye, Kaye’s and Malleson’s History of the Indian Mutiny, 1857-58.

30 Bell, “The 1858 Trial of the Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah II ‘Zafar.’”

31 “Proclamation of the King-Emperor.”

32 Ibid.

33 Islamuddin, “Legalising the plunder,” 670-82.

34 Ibid., 671.

35 Russell, My Diary in India, 329-34 and 337-38.

36 Ibid., 356.

37 Peel Commission Report; Rand, “Reconstructing the Indian army after the rebellion.”

38 For an account of the plans that were realized, see Oldenburg, The Making of Colonial Lucknow, 1856-77.

39 For a detailed description of this experience, see Cuthell, My Garden in the City of Gardens.

40 Despatch no. 20, 22nd March 1951. p15. British Library IOR R/4/84.

41 When, after Indian independence, the status of mutiny memorials was being negotiated, the designated officer from the U.K. Home Office had to be reminded by the Archbishop of Lucknow that most of the Christian congregations in these cities were Indians and not Britons.

42 Cohn, Colonialism and its Forms of Knowledge.

43 Talboys, The History of the Imperial Assemblage at Delhi.

44 Metcalf, The Aftermath of Revolt.

45 The Reverend Thomas Moore’s Letters.

46 Ibid., Jan 15, 1858.

47 Russell, My Diary in India, 208.

48 Stewart, “Preface,” xv.

49 After witnessing the hanging of a rebel without struggle, Thomas wrote to his mother that such unwillingness to struggle was exceptional: “sometimes the poor beast jumps of [sic] the door, and has to be hauled up, one man was thus tumbled down 3 times with his Exec and was at last let go and was then kicked abt [sic] to the intense delight of the soldiers & sailors proving that Englishmen can be Brutes as well as the natives” (The Reverend Thomas Moore’s Letters).

50 Metcalf, The Aftermath of Revolt, 327.

51 Ibid.

52 Ibid.

53 Hobbes, Leviathan, 132-33, 152-57.

54 Ibid., 194-95.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bell, Lucinda D. “The 1858 Trial of the Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah II ‘Zafar’ for ‘Crimes Against the State.’” PhD diss., The University of Melbourne, 2004.

Benton, Lauren. A Search for Sovereignty: Law and Geography in European Empires, 1400-1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Brown, Wendy. Walled States, Waning Sovereignty. New York: Zone Books, 2010.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. “‘In the name of politics’: Sovereignty, democracy and the multitude in India,” Economic and Political Weekly 40, no 30 (July 23-29, 2005): 3293-3301.

Cuthell, Edith E. My Garden in the City of Gardens: A Memory with Illustrations. London: John Lane, 1905.

Despatch no. 20, 22nd March 1951. p15, Historical Monuments in India: Mutiny Memorial Well at Cawnpore, File 11/1b, British Library IOR R/4/84.

East India (Proclamations). “Proclamation, by the Queen in Council, to the Princes, Chiefs and People of India” (published by the Governor-General at Allahabad, November 1st, 1858), India Office, 13 November 1908.

———. “Proclamation of the King-Emperor to the Princes and Peoples of India, read by His Excellency the Viceroy in Durbar at Jodhpur on the 2nd November, 1908.” India Office, 13 November 1908.

Foucault, Michel. “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the College de France, 1975-76, trans. David Macey. New York: Picador, 2003.

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan. London: Oxford University Press, 1929.

Hussain, Nasser. The Jurisprudence of Emergency. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003.

Islamuddin, Shaheen. “Legalising the plunder in the aftermath of the uprising of 1857: The city of Delhi and ‘prize agents.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 72, Part-I (2011): 670-82.

Kaye, John. Kaye’s and Malleson’s History of the Indian Mutiny, 1857-58. Edited by Col. Malleson. London: W.H. Allen, 1892.

Metcalf, Thomas. The Aftermath of Revolt, India, 1857-1870. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1964.

Moore, Thomas. “The Residency of Lucknow on the 1st July, 1857,” British Library, Add MS 37152 A.

———. The Reverend Thomas Moore Letters. British Library, Mss Eur/F630/2.

Moore, Thomas and Dorothy Moore. “Twenty-six coloured views of buildings, etc.,” British Library, Add Ms 37153.

———. “Plan of The Three Advances on Lucknow,” British Library, Add MS 37152 B.

Peel Commission Report. Report from the Commissioners. 1859.

Oldenburg, Veena Talwar. The Making of Colonial Lucknow, 1856-77. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Rand, Gavin. “Reconstructing the Indian army after the rebellion.” In Mutiny at the Margins: New Perspectives on the Indian Uprising of 1857, vol. 4, edited by Gavin Rand and Crispin Bates. New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2013.

Russell, William H. My Diary in India in the Year 1858-59. London: Routledge, Warne and Routledge, 1860.

Sen, Sudipta. “Unfinished conquest: Residual sovereignty and the legal foundations of the British Empire in India,” Law, Culture, and the Humanities 9 (2): 227-242.

———. Distant Sovereignty: National Imperialism and the Origins of British India. New York: Routledge, 2001.

Sreedhar, Susanne. Hobbes on Resistance: Defying the Leviathan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Stewart, Kathleen. “Preface.” In Affective Landscapes in Literature, Art and Everyday Life: Memory, Place and the Senses, edited by Christine Berberich, Neil Campbell, Robert Hudson. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2016.

Wheeler, J. Talboys. The History of the Imperial Assemblage at Delhi, Held 1st January, 1877. London: Longmans, Green, Reeder and Dyer, 1878.