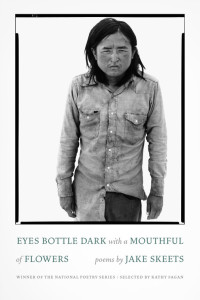

Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers

Jake Skeets

Milkweed Editions, 2019

Reviewed by Weston Morrow

Jake Skeets’s collection, Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers (Milkweed Editions, 2019) is rife with natural imagery and its relation to the human body: “cracked hawkweed sacrum” and “His hair horsetail and snakeweed.” Skeets interweaves this natural imagery, not as a common sort of metaphor—which reinforces the boundary between two things even as it relates them—but rather as a direct commingling between human and non-human bodies.

In As We Have Always Done, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson writes, “We need to continue and expand rooting the practice of our lives in our homelands and within our intelligence systems in the ways that our diverse and unique Indigenous thought systems inspire us to do, as the primary mechanism for our decolonial present, as the primary political intervention of our times.”

Both the land and the Indigenous male body in Eyes Bottle Dark are living vessels run through with settler-colonial infrastructure:

………………………………….His eyes bloodshot and flaxen from the lamplight. My

tongue runs across his shoulders, stone bells affixed to bone. Cathedral noise in

the socket, a rotten lisp. Pipelines entrench behind his teeth. I hear a crack in his

lung like burning coal.

When Skeets interweaves the human body and the land, there’s no naive pastoral optimism. The land is a body at risk, as is the Indigenous body Skeets describes. Throughout the collection, the image of earth as body commingles with that of the queer, male, Indigenous body, and neither is able to find solace in the other. Like two boys, desperate to touch, but still figuring out how to do so, the earth and the human body blur along each other’s edges through much of this collection.

The two do touch, but not in a way that satisfies desire. In setting the scene of Gallup, New Mexico, Skeets immediately foregrounds an image of place in which man and nature are constantly touching in sinister ways:

Drunktown. Drunk is the punch. Town a gasp.

In between the letters are the boots crushing tumbleweeds,

a tractor tire backing over a man’s skull.

–

Men around here only touch when they fuck in a backseat

go for the foul with thirty seconds left

hug their son after high school graduation

open a keg

stab my uncle forty seven times behind a liquor store

There is little tenderness or love in this touch—between men and the land, between men and other men. Skeets builds the image of men who cannot touch in a way that opens themselves up to vulnerability, which leads instead to an otherness between bodies.

Skeets compares the body to a bottle, its desires roiling inside, trapped, under extreme pressure, like oil and coal shot through the earth. Both vessels are tapped, drained of that essence by men:

boys only hold boys

like bottles

Skeets talks of the body as bottle—how, when you’re drinking, you can cradle a bottle in your hand, can long for what’s inside, all that desire caught in the bottle. Until it’s empty, and then you throw the thing away, watch it shatter, left broken, like a body in the grass on the road verge.

There is a bleakness to Skeets’s collection, but there is hope there, for those willing to take the time to find it. Skeets eschews Euro-American forms for most of the collection, choosing instead to craft the lines toward the enactment of Gallup, and the precarity of Indigenous male bodies, on the page. But, intriguingly, the final poem, “In the Fields,” (there are four poems so named) is a sonnet written in couplets. What are we to make of this move, at the very end of the book, to utilize that most canonical of forms? Given the poem’s content—a calling back the self into Diné tradition as a guide for beneficial commingling of bodies, man-to-man and man-to-land—Skeets’s simultaneous calling back to poetic tradition indicates, also, a desire to pull poetic tradition into that light:

We could be boys together finally

as milk vetch, tumbleweed, and sticker bush.

We can be beautiful again beneath

the sumac, yarrow, and bitter water.

There is a materiality to the language in Skeets’s collection. The shape of the words takes the form of a body walking, staggering through Gallup—the town and its inhabitants embodied in the words on the page. When Skeets writes, “In between the letters are boots crushing tumbleweeds,” he demonstrates the two-way connection between place and page. Not only does Skeets perform an ekphrasis of the cover image (an old photograph of his uncle), he simultaneously paints a visual portrait of his own on the page. The ekphrasis crafts a new visual, as well as linguistic, image. Skeets’s use of white space—into which men disappear and bodies disintegrate—often conveys as much information as the letters on the page. In the third of four poems titled “In the Fields,” Skeets layers the image of a body decomposing through space as well as language:

r

o

w

s

remains

like

e

t

t

e

r

s

In Shapes of Native Nonfiction, Elissa Washuta and Theresa Warburton write of the materiality of language and the holistic union of content and form: “This work creates rather than merely reflects the world. . . . Which world(s), then, are being created herein?”

Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers constructs an image on the page—an image of specific people and places. The book’s cover image serves as an ekphrastic center for the collection. The emphasis on materiality in language and the use of form in Skeets’s ekphrasis effectively construct images on the page, building a new visual alongside the linguistic ekphrasis of the photograph.

In her article, “Disrupting a Settler-Colonial Grammar of Place,” Mishuana R. Goeman writes of the photographs taken by Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie, “This ‘repatriating of the erotic’ plays with the image of the Native’s close alignment with the land and the fact that body and land must be tamed and ordered according to a settler-colonial grammar of place.”

Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers staggers and drags us through a very real settler-colonial landscape but interweaves, too, the threads of a better one, where the vessels of the body and the earth might be bound together in harmony, restored.