Yang Yongliang

Shan Shui in the Digital Age

Yang Yongliang’s unique approach to rendering landscape synthesizes his early study in traditional brush painting with his schooling in photography and video art. This convergence of old and new, in Yang’s philosophy, is the best method to capture the modern China. Parallel to Yang’s path, the People’s Republic of China is rapidly adapting and transforming itself to a hyper- urbanscape. The artist’s work calls attention to the staggering cost of this path. In China’s quest for modernity, sprawl has colonized and cannibalized nature.

Yang’s 2017 video Prevailing Winds brings palpable energy and life to a digitally created landscape. Seen from a bird’s-eye view, moving cars fill the roads and construction projects perpetually build a city that is overtaking an island mountainscape. At 4K resolution, one can make out small figures walking among demolition sites, but the overall shape of the city confounds; it does not match any logical urban layout. A methodically urban soundtrack mixes with the sounds of wind and water, gradually building to a crescendo as the city’s rhythm fast forwards into a surreal, chaotic sprint.

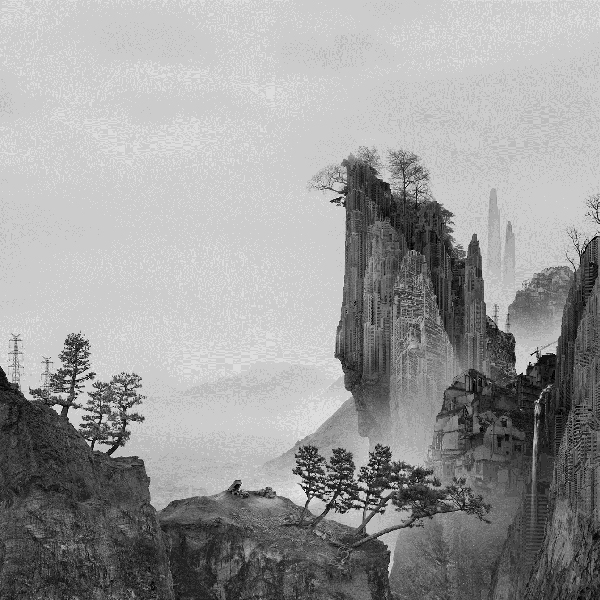

To those conversant with Chinese art, Prevailing Winds takes the form of one of its most powerful symbols, a Song Dynasty landscape. In China’s long history, the Song era (964–1238) was a period of great florescence in arts and culture, during which artists took landscape imagery (shan shui) to extraordinary new heights. While the depiction of flora, fauna, and natural features had been an element of painting since Han Dynasty (220 BCE–220 CE) tomb murals, artists would not begin seeing and studying landscape as a separate genre until China’s Tang Dynasty (600–938). Over the next centuries painters experimented with form and color, transforming rocks, mountains, water, and trees into symbols of nature. Some believed the clearest representation came not from full color but rather through a monochrome palette that represented inner reality. Artists like Fan Kuan (10th–11th century) combined these elements into a monumental form, creating seven-foot-tall landscapes that celebrate the vastness and multiplicity of creation.

A contemporary of Fan Kuan, the painter Guo Xi (ca. 1000–1090) discussed his philosophy about the genre with his son. One lesson began, “Why does a virtuous man take delight in landscape? That in a rustic retreat he may nourish his nature; that amid the carefree play of streams and rocks he may take delight The din of the dusty world and the locked-in-ness are what human nature habitually abhors.” In another lesson, Guo Xi told his son “there are landscapes in which one can travel, landscapes which can be gazed upon, landscapes in which one may ramble, and landscapes in which one may dwell. One suitable for traveling in or gazing upon is not as successful as one in which one may dwell or ramble.”1 To Fan Kuan and Guo Xi, many traits were necessary to produce a great landscape, but their works shared a significant commonality. In their landscapes, nature abounded, but the presence of man was minimal. One has to look hard to find a small scholar’s hut or a dirt path leading the eye through an image meant to exalt nature.

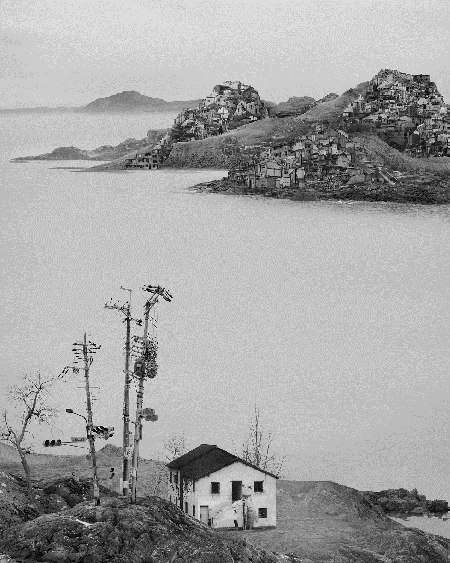

Prevailing Winds takes the shape and form of a Song monumental work, but Yang inverts some of the lessons of Guo Xi. Viewers may enjoy gazing upon or allowing their eyes to wander through this landscape, but can anyone fathom living in the midst of this digital city? The trademarks of the generic city densely pack much of the land and seem to climb endlessly into the sky. What appear to be open areas are only temporary pauses in order to make way for more development, towers, and power lines. Little strips of trees in random locations hint at parks that are human attempts to control and mimic nature. The flurry of crane activity and demolition of old architecture remind viewers of the ugly steps authorities carried out to achieve the present. In the 1990s and 2000s, the controversial process of Chaiqian meant the destruction of old housing units and the relocation of their residents.2 Like past artists who spent time in nature to understand it, Yang absorbed himself in the districts of Shanghai and other Asian cities that were undergoing these transformations.

Only water is left, but in contrast to Song era paintings, water is not a placid lake or stream but a raging force that surrounds and bisects the city. One can see the erosion it has caused, laying bare the rock in several areas. This representation perhaps reflects the challenges water poses to twenty-first century China. Unchecked, rapid industrial growth is a leading factor in climate change, and warmer temperatures lead to rising sea levels, more powerful typhoons, and intense episodes of flooding in Shanghai and other coastal cities.

Parallel to China’s urban changes, the Chinese art world has also grappled with old and new forms. For some contemporary artists, landscape painting and calligraphy have little relevance in the twenty-first century. Yang, however, embraced a unique middle path, believing new technology— including digital cameras, images, and editing software—combined with the foundation and philosophy of shan shui does not distort the intention of landscape painting but rather continues it. “As long as the characteristics don’t change,” he has stated, “the media you use to express the art doesn’t matter.”3

As a young artist, Yang Yongliang (Chinese, born Shanghai 1980) studied traditional Chinese painting with calligraphy master Yang Yang. He graduated from China Academy of Art in Shanghai with a degree in visual communication in 2003. Yang’s work has been exhibited internationally at museums and biennials, such as Thessaloniki Biennale in Greece (2009), Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing (2012), National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne (2012), Moscow Biennale (2013), Metropolitan Museum of Art New York (2013), Daegu Photo Biennale in Korea (2014), Singapore ArtScience Museum (2014), Modern Art Museum Paris (2015), Fukuoka Asian Art Museum (2015), Somerest House London (2016, 2013), and the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney (2016, 2011). His work is in many notable public collections including the British Museum, Brooklyn Museum, How Art Museum in Shanghai, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, San Francisco Asian Art Museum, and many more. Yang Yongliang currently lives and works in New York City.

Yang Yongliang (Chinese, 1980), The Brook, 2016, film on lightbox, 20 cm x 25 cm, courtesy of the artist.

Yang Yongliang (Chinese, 1980), The Streams, 2016, film on light box, 25 x 20 cm, courtesy of the artist.

Yang Yongliang (Chinese, 1980), Lone House, 2016, film on light box, 25 x 20 cm, courtesy of the artist.

Yang Yongliang (Chinese, 1980), The Path, 2016, film on light box, 20 x 20 cm, courtesy of the artist.

Yang Yongliang (Chinese, 1980), The Cliff, 2016, film on light box, 20 x 20 cm, courtesy of the artist.

Yang Yongliang (Chinese, 1980), Prevailing Winds (still), 2017, 4K video, 7 minutes, courtesy of the artist

Yang Yongliang (Chinese, 1980), The Flock, 2016, film on light box, 20 x 25 cm, courtesy of the artist.

NOTES

1 Kuo Hsi, An Essay on Landscape Painting, trans. Shiho Sakanishi (London: John Murray, 1935), 30-32.

2 Qin Shao, Shanghai Gone: Domicide and Defiance in a Chinese Megacity (New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2013), 2-3.

3 “Saving Chinese Art From Extinction: Meet Yang Yongliang” (The Creators Project, 2012), 6 mins., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZgYdQUn-cIk.